It’s always distressing to see situations in which the cure to a social disease looks pretty bad in itself. For me, many of these situations revolve around the concept of progressive punitivism–situations in which social justice activists and advocates pursue equality, fairness, and other good stuff through punitive means (here‘s a podcast I did about this.)

Progressive punitivism can operate through the formal legal system (as it does when mayors call to reverse the burden of proof in criminal cases featuring cross-racial violence or when activists pursue vindictive recall campaigns against judges they deem too lenient) or, at least just as commonly, through the informal punitive machine of hard-to-reverse reputational harm, referred to in social media as “cancel culture.”

Many people have written about the ills of the prevalent virtue signaling and virulent shaming mob campaigns of he progressive left, especially in the context of what is known as “carceral feminism“. Aya Gruber’s recent book The Feminist War on Crime offers a critical examination of the allegation-as-fact narrative and what it means for the carceral state. And Leigh Goodmark’s Decriminalizing Domestic Violence suggests alternatives to the common domestic-abusers-are-inhuman-monsters narrative that permeates even progressive conversations about crime. In short, one of the serious problems with carceral feminism is that the progressive commitment to due process ends the minute we find ourselves facing a defendant we dislike.

Perhaps as a reaction to the contradictions between carceral feminism and cancel culture on one hand, and the abolitionist stance that the same folks tend to hold regarding the U.S. criminal justice system on the other, alternatives have been proposed, including the notion that harms of the patriarchy can be resolved outside the formal legal process, through restorative justice processes. One of these alternative process, Transformational Justice, takes on issues that are typically regarded through a punitive lens among progressives–domestic abuse, sexual assault–and offers a survivor-centered process that involves the community. You can read more about the premises behind transformative justice here. Central to the process is the establishment of “pods”: a “survivor pod” that supports the survivors and amplifies their narratives, and an “accountability pod” that accompanies the perpetrator’s journey toward accepting responsibility and offering redress of harms. The Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective defines the pod as “the people that you would call on if violence, harm or abuse happened to you; or the people that you would call on if you wanted support in taking accountability for violence, harm or abuse that you’ve done; or if you witnessed violence or if someone you care about was being violent or being abused.”

It is not surprising that sex-positive communities, such as the polyamorous and/or kink communities, are eager to adopt restorative practices. Polyamorous people have been on the receiving end of horribly discriminatory legal action, ranging from heart-wrenching custody battles to lack of police support in the face of hostilities. BDSM and kink practitioners have had to defend themselves against criminal charges with meager legal protections. Both communities regard consent as the centerpiece of their ideologies: polyamorous speakers often present polyamorous relationships as the opposite of cheating and kink practitioners develop protocols for consent before engaging in sexual scenes. When cheating and nonconsensual interactions occur in these communities, the harm is not only to the victims, but also the already vulnerable reputation of communities that are underserved and misunderstood. Which is why it makes sense that these communities have recurred to “accountability processes” to resolve these situations. In some cases, there’s fear that seeking recourse through police intervention will be futile at best, or worsen the situation at worst. In other situations, the harms would not trigger legal intervention, either because the incident would not be perceived as serious enough or because it does not constitute a criminal offense, even though it matters a great deal to the participants.

I’ve recently looked through the Internet chronicling of two such processes: the accountability process for sex educator Reid Mihalko and the accountability efforts lobbed at polyamorous author and speaker Franklin Veaux. While I’ve been a long-time researcher of political and legal mobilization in the context of underserved sexual communities (see here, here, and here), I don’t personally know either of these two men or any of their accusers, even though two of the people who participated in the pods and/or wrote about them are friends, acquaintances, and colleagues. I am completely agnostic on the facts and perceptions that surrounded these incidents, except for the obvious fact that the survivors experienced immense suffering and trauma, sometimes spanning years. My only source material is what’s publicly available online, which turns out to be quite a lot, but I haven’t attempted to uncover “the truth,” whatever that means. My commentary on this mostly seeks to understand what these processes seek to achieve and whether (and to what degree) they feel qualitatively different from the process this was supposed to complement or replace.

In January 2018, The Daily Beast publicized accusations against Mihalko, according to which, eight years earlier, he pestered Kelly Shibari, an adult performer who attended a workshop of his, into giving him a hand job. The article emphasized two aggravating factors: the exploitation of a sex worker, whose consent is already suspect and vulnerable to doubt, and the incongruence of the incident with Mihalko’s public image, particularly the emphasis he placed on consent at his workshops and events.

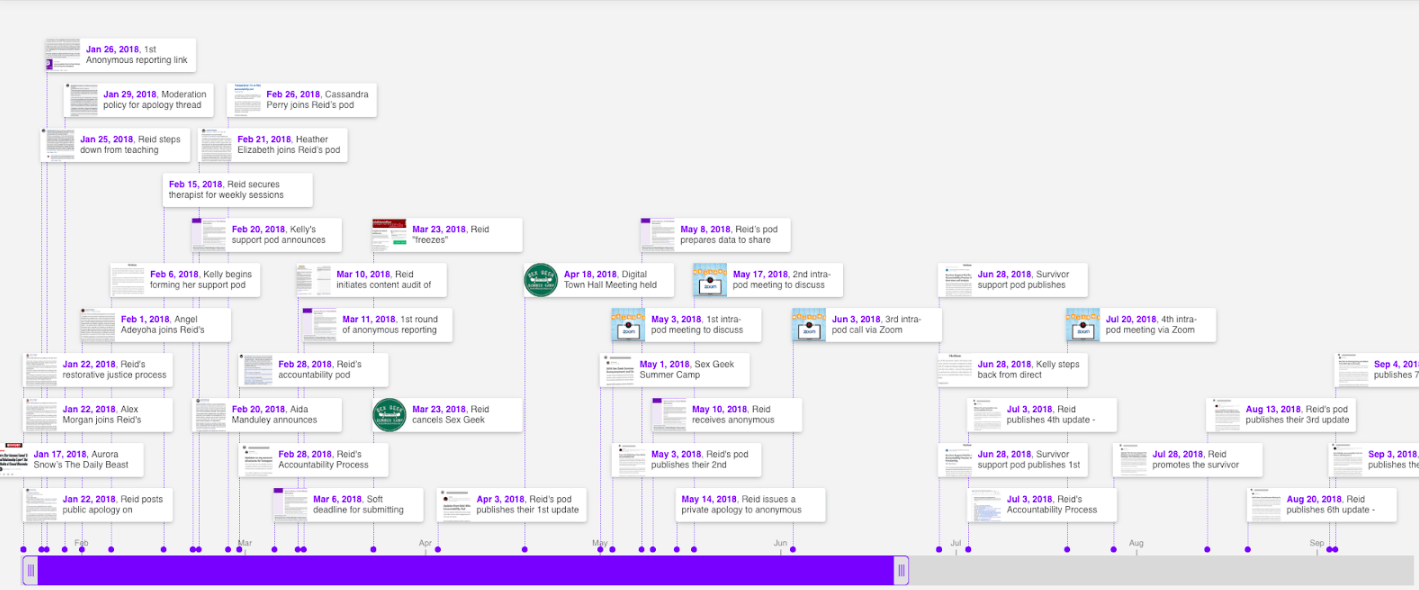

Mihalko quickly published a public apology on Facebook and subsequently announced that he would step down from teaching. Two pods formed: An accountability pod for Mihalko and a survivor pod for Shibari. The accountability pod created a link for soliciting more anonymously submitted stories about Mihalko, with a “soft deadline” in early March. The entire process, which consisted of writings by the accountability pod members, writings by Mihalko himself, and accounts of the progress made (including securing a therapist for Mihalko) was publicly shared on Medium.com. The public face of the process included accounts from the survivors; 12 of these stories were included, as well as an “analysis” by the survivor pod members, which concluded:

“Overall, the stories consistently depict a person who, often while under the influence of alcohol, crosses boundaries in both overt and covert ways, and mingles sexual behavior (including flirting and propositions) with connections with people that are not in specifically sexually-appropriate environments. There were multiple mentions that Reid seems to specifically seek out sex from people who may not have strong boundaries around him, possibly due to the assumption that Reid is an expert and/or has professional influence. A number of people noted that Reid seemed to be unaware of the effect of his privilege & power as an educator / expert in gaining consent. Multiple people noted that they did not feel that Reid picked up on cues that they were uncomfortable with being flirted with and/or that they did not want to engage sexually.”

I was struck by how similar this assortment of Medium posts was to the dynamic in parole hearings that I uncovered and analyzed in Yesterday’s Monsters. For one thing, the idea of allegation-as-fact, which Gruber discusses in The Feminist War on Crime, is prevalent in both proceedings. At a parole hearing, the courtroom transcript is king: any deviation from the story as it was told by the prosecutor in the courtroom is “minimizing.” Here, the allegation is queen. The idea that the allegation is true simply by virtue of being alleged shapes the discourse, and is presented as as antithetical to the official process, which would harm victims by questioning their credibility. By contrast, any effort by Mihalko to dispute this assessment would be regarded as a minimization of his role in the incidents.

Similarly, apologies begat criticism, which begat more apologies–for the better part of the few months covered by these posts. Some of Mihalko’s apologies were perceived as undue “centering” of himself, rather than of the people he had harmed. The effort to push more and more self excavation and inquiry reminded me of the decades-long parole hearing efforts to get people to “authentically” talk about the “insight” they have gained. There is the perception that these pods (members of whom are also, in part, celebrities of the sex-positive community–either self-appointed or picked by Mihalko and Shibari) could discern when Mihalko would finally get to the bottom of the apology well and emerge with a fully and appropriately contrite version of his apologies. Until then, apologies begat apologies. I don’t claim to have the power to discern authenticity, or lack thereof, or an instrumental effort to save his reputation, from Mihalko’s contrite posts on Medium (you may come to a different conclusion–read here and judge for yourself–but robust social psychology research suggests we are not good at all at determining this.) They remind me a lot of the parole transcript stuff, echoing the iconic scenes in The Shawshank Redemption in which Red repeatedly assures the board that he is completely rehabilitated: “no danger to society here, and that’s God’s honest truth.”

Another way in which this process reminded me of parole hearings has to do with the role of the survivors. By contrast to the criminal process, where the victims (understandably) perceive themselves as powerless, it was Shibari who asserted control over the survivor pod and the gathering of the other survivors’ stories. This is understandably more empowering to survivors than a situation in which the system takes ownership of the victim’s narrative, but as Kent Roach points out, providing victims/survivors with agency does not necessarily uproot the punitiveness of the process. If this process is focused on the healing of Shibari and the other survivors, it adopts a very particular interpretation of what healing means.

By contrast to Mihalko’s cooperation with the accountability pod, Franklin Veaux’s case exemplifies how these public processes with “accountability pods” operate when their target does not cooperate. Like Mihalko, Veaux built his public persona as a polyamorous educator around notions of healthy relationships, consent, and healthy communication practices, which he espoused in his public talks and in his book, coauthored with former partner-turned-accuser Eve Rickert. The accusations against him, again, are aggravated by the contrast between this benign public persona and his behavior in private relationships. His survivor pod elaborated in an open letter, which referred to their inquiry into Veaux’s behavior as “polyamory’s #metoo”:

“The women’s experiences indicate that Franklin has patterns of manipulation, gaslighting, and lying; leverages his multiple partners against one another; tests or ignores boundaries; pathologizes his partners’ normal emotions and weaponizes their mental illnesses; exploits women financially; uses women’s ideas and experiences in his work without permission or credit; grooms significantly younger, less experienced, or vulnerable women; lacks awareness of power dynamics and consent; has involved women in group sex and other sexual activities that they experienced as coercive; and accepts no responsibility for the harm he causes by engaging in these behaviors — often blaming other women, or the harmed women themselves, for that harm.

These behaviors escalate when Franklin lives with a partner, and he becomes verbally abusive when his nesting relationships end. The severity of this pattern is illustrated by the fact that none of his former nesting partners will be alone with him. Two of them, over a decade apart, fled the homes they shared with him at the end of the relationships. Their written records from the time of leaving him show evidence of trauma.”

But the process of holding Veaux accountable for these harms went awry from the survivors’ perspectives. In an open letter they wrote on their own behalf (rather than by the pod), also published on Medium, they wrestle with what procedure should be in this kind of “transformative justice” process:

“In our understanding of transformative justice practices, the survivor pod centers the needs and input of the survivors, in turn informing the actions of the accountability pod. That didn’t happen in the part of this process that involved Franklin’s pod. From the time that someone representing an accountability pod first made contact with Reid until just before “An Announcement About Pod Boundaries” was posted, no survivor was consulted or given meaningful opportunity to influence the actions of the survivor pod toward Franklin’s pod, or given access to the communications between the pods. Our list of asks was not sent, and we were not given an opportunity to make additional requests, or to decide what information, if any, to share with Franklin’s pod. The survivor pod has said more about this in their wrap-up statement.

“Those of us who have taken the time to read through the correspondence between the pods do not agree with the approach the survivor pod took and do not believe it represents us, or the values this process was intended to be founded on. We also disagree with some of the characterizations made in the pod boundary statement. Because this cannot be undone and does not materially affect the way forward now, we will leave it at that.

“To be clear, not all of us were even invested in a transformative justice framework when we came forward. Those of us who were, sincerely believed in it. But regardless of intent, it is clear that such a framework was not in place during this process. Nor do we believe that Franklin would ever have engaged in an accountability process in a way that was ever more than performative — we believe his many public pronouncements about us prove as much. This clarification should therefore not be taken in any way as a vindication of Franklin or his own pod members. But it is time to set aside any pretense that a transformative justice or accountability process has occurred here, or will.”

Several things seemed to have gone awry. The survivor pod members admitted that they engaged in some exchanges with Veaux’s pod that were not divulged to the survivors themselves; in a particularly curious procedural twist, the survivor pod appointed Mihalko (yes, the subject of the supposedly exemplary accountability process) to liaise with Veaux on behalf of the pod, a move that was not successful and not coordinated with the survivors themselves (this raises an ancillary question, which is whether people subjected to versions of this process that are deemed successful are ever fully redeemed, to the point that they are regarded as assets in others’ process; I’ve seen this sort of empowering move in peer-to-peer networks of formerly incarcerated people, but this process is supposed to be centered around the wishes of survivors, rather than about the redemption of former accountability process subjects, so it’s a completely different story.) Another part of what went awry, according to the survivor pod, had to do with the fact that the basic assumptions underlying the process were not shared by the two pods–the survivor pod, which sought to amplify the voices of survivors (albeit not in the way the survivors wanted and without informing them or seeking full input from them), and the accountability pod, some of whose members did not accept accountability as given and disputed credibility.

This, I think, is the crux of the matter. Reading the different facebook posts, Medium posts, and Quora questions, is complicated, because transformational justice (like a lot of formal and informal processes) is heavily laden with jargon and terms of art (“transformational” “pods” “accountability” “centering” “amplifying”, and that’s on top of the relationship jargon (“harm”, “gaslighting”, “problematic”, etc) and the considerable specialized verbiage developed around consent and relationships specifically for poly and kink communities. But underneath this intricate terminology there seems to be a simple idea: a necessary condition for supporting survivors is accepting their narratives at face value. Questioning their credibility in any way is a violation of the basic assumptions of the accountability process. In other words, if you “plead not guilty”, or even ask for the transformational justice version of an Alford plea (acknowledging the suffering but not taking on full responsibility for it), you are not deemed a good-faith participant in your accountability process and the whole transformational justice edifice breaks down. What seems to have gone awry, beneath the layers of process and prose, is that Veaux did not accept the survivors’ narrative (he argued that he was the victim of a smear campaign orchestrated by Rickert); the members of his pod who spoke publicly also expressed less than wholesale acceptance of the survivors’ versions of the events (albeit to a much lesser degree than Veaux himself.)

Indeed, eventually, the breakdown of the process because of this basic gap in factual accounts saw the survivors break with the pod and the prcess and assert ownership of their own narratives. The culmination of this break was the publication of their stories, as interviewed by Louisa Leontiades, in a website called “I tripped on the (polyamorous) missing stair.” The open letter refers to it as a “survivors’ archive. Nothing more, or less.” Indeed, the suffering is evident and heartbreaking. Reading the testimonials feels like watching a train wreck–tragic, elegant, generative of questions. In an odd subversion of the allegation-as-fact ethos, the document collection itself has evoked debates and disputes not only about credibility, but about methodology, and about the interpretation of methodology, and about the methodology of interpretation of methodology. These posts feel a bit like the story of the blind men who set out to inspect an elephant and, underneath all the fancy analysis, they all revolve around the inescapable conundrum of credibility.

Looking at the presumably successful process in Mihalko’s case, and at the unsuccessful (assessed by the survivors themselves) process in Veaux’s case is instructive. It is clear that, in both cases, the people running the process are doing so with good intentions, but it is not entirely clear what those intentions are, or whether there is consensus about them. It’s clear that the process is supposed to be “survivor centered”, and that the survivors play a role in it that is greater than what they would play in the official legal system. Indeed, since a lot of the experiences that the survivors and pods describe are examples of poor (and traumatizing) interpersonal behavior, but do not constitute criminal offenses, they certainly get more agency naming their grievances than they would get if they filed a complaint with the police. Nonetheless, it’s not at all clear what the survivor participation/leadership means or even that the survivors, as a group, are clear on it themselves or in agreement amongst themselves. It is pretty clear that the pod members are well meaning in stepping in, but it is not at all clear what the yardstick is for naming them, and what sort of authority and expertise they claim, nor is it clear whether their determinations or guidance would or should be acceptable to the person who is to be held accountable (when the person flouts their presumed authority, such as in Veaux’s case, what does this authority even mean?) It is pretty clear that some measure of sincere accountability needs to flow from the perpetrator–and it’s clear that none was forthcoming from Veaux–but it is not clear at all what the yardstick is for determining what sort of contrite expression will be deemed sufficient, how sincerity is measured, and how the pod determines when the penance is done and the person (who, in both cases, holds himself out as a public celebrity educating others on good relationships) “gets” to resume his public life. What does the “certification” that the person has “done the work,” as they say in progressive circles, mean? Even in the event that, as in Mihalko’s case, the pod eventually rinses him of the reputational stain, is the stain really gone when the process is public for the sake of transparency?

I applaud the earnest and well-meant effort to find an alternative to the criminal process on one hand, and to the social media mob-shaming spectacle on the other. Both of these things are destructive, and the project of empowering survivors to tell their stories is laudable. But overall, I’m not sure that transformative justice really has presented a better alternative. It appears to be a more elaborate, erudite, and articulate version of the trial-by-social-media that is Twitter; it retains much of the pathology and does not present a fully salutary alternative. Moreover, it seems not to have bypassed two of the central problems of all processes designed to address interpersonal and sexual misbehavior: the engagement with the credibility of narratives and the buy-in (call it “admission of guilt” or “accountability”) on the part of the accused party.

First, the credibility. The idea of allegation-as-fact, or #believewomen, emerged as a contrary notion to the pathological lack of respect and credibility questioning that victims of interpersonal misbehavior, particularly domestic violence (“why didn’t she leave?” and sexual assault (“what were you wearing?”) survivors encounter in police stations and courtrooms. But it seems that the effort to either present these narratives without testing their credibility, or with an explicit statement that they are to be believed, does not quell the understandably human urge to “find out what happened.” Even the folks that have done the erudite meta-analyses, particularly in Veaux’s case, are concerned with credibility; within this women-positive, sex-positive process, they engage in contrasting factual stories. Rather than believing that people have suffered–which should be obvious just from the tenor of the narrative, before even engaging with the particulars–the focus becomes on believing their account of what happened; the former is seen as an insult, and expressing regret just for the suffering, without giving the allegation full credibility, is a worthless “non-apology apology.” Pretty much what you get from the legal system and/or the social media cancel culture machine. Ultimately, transformative justice can only transform perpetrators who walk into the process fully prepared to accept the narrative of the survivors. Any effort at insisting on transformation if this basic condition is not met is not only futile, but destructive.

Relatedly, assuming–and I’m not sure that assumption is true at all for all the survivors, given their own statements–that there’s value in being offered an apology, and assuming–and I now this assumption is not true, because social science literature refutes it–that it is possible to detect sincerity in apologies, the success of an apology or an acceptance of accountability depends entirely on the extent to which the perpetrator even buys into the process. With public figures, even in a progressive, feminist, queer-friendly space, there are huge disincentives from buying into the process. The threat of withdrawal of social capital has to be considerable to convince someone to participate. And even when the buy-in is complete, as in Mihalko’s case, one is left with the unsatisyfing taste that an apology that is offered in the context of a tribunal that offers you a stamp of approval back into public life can never be 100% genuine. This is what Nick Smith talks about when he argues against court-ordered apologies. Which raises the question: Does buy-in matter for what the survivors get out of the process? I’m not sure whether Shibari and the other survivors in Mihalko’s eventually walked away from his accountability process feeling fully satisfied with the outcome, but we do know that Rickert and the survivors in Veaux’s case were unhappy with the aftermath and attributed its failure in part to the pod’s positions and process. Again, it is hard to argue that the question of credibility is not a big part of this.

I wish I knew how to offer an alternative to this process that would bring about healing without the aftertaste of credibility testing and punitivism. I used to think that the problem is that we’ve been steeped in the idea of punitivism for so long. But after having read Paul Bloom’s Just Babies, I think that notions of retribution are an important part of our psychological makeup since infancy, and dealing with them inevitably requires us to wrestle with the complicated question of “what really happened.” Much as we try to escape it with concepts of survivor empowerment, we end up exactly where we started: comparing shards of narrative, selling ourselves unknowable truths, and refusing to accept that incidents can be experienced in radically different ways by different people. And maybe, when we experience immense suffering at the hand of someone else, the most important thing to us is not just to be listened to, but also to be found credible, to be believed. And if that’s the case, I don’t know how we square this with due process, restorative process, or any process.

This conversation goes straight to the heart of the non-choice we face in the November 2020 election: vote for the Democratic candidate, who has been accused of sexual misconduct, or for the incompetent, psychopathic, semi-literate, despotic career criminal. If we are to save the country, we have to figure out how we handle the moral and factual vagueness around these accusations, and sit with what it means to walk through the woods of credibility. That there is no real alternative (an abstention or a write-in is a vote for Trump, I’m pretty clear on that) makes this even more confusing. And yet, we should wrestle with the meaning of supporting suffering, and whether that is inexorably tied to questions of credibility and buy-in.

No comment yet, add your voice below!