The last few days have seen numerous stories discrediting Tara Reade, the woman who accused Joe Biden of rape, to the point that convictions based on her testimony could be overturned.

After reading these stories, I sat with my emotions, realizing I predominantly felt relief. Now I could vote for Biden, which I was going to do anyway, *and* not feel like a person tainted with badness and dishonesty. I am not the hated, unprincipled centrist! I am not a traitor to the feminist cause! I can be utilitarian and good at the same time! Looking around progressive social media, I could read the same sentiment between the lines of all commentators rushing to malign Reade. We are vindicated as Good People (TM) and can go ahead and do the right thing with our virtue unsullied.

This sense of relief told me something important–something that I had been talking around for years, even as I wrote about the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings and about progressive punitivism in general. Regular readers know that the progressive tendency to fiercely advocate for due process and abolitionism and all that jazz, only as long as it’s not someone we (the collective “we”) hate, has irritated me for years. In my article about progressive punitivism I ascribed this tendency to the overall prevalence of punitivism as the go-to tool to approach any social malaise. Americans of all stripes and political persuasions, I said, have been so steeped in the idea that the only tool they have is the criminal justice hammer that now everything looks like a nail to them.

I’m beginning to think I’ve let progressives off the hook too easily. As I recently said, I’m realizing that, even in the most supposedly benign, nonpunitive, restorative, transformative, call-it-whatever-fancy-name-you-like process, the bottom line–even when wrapped in do-gooder jargon, everything boils down to the underlying question: What happened? Is the victim telling the truth? Is the offender telling the truth? Who should we believe?

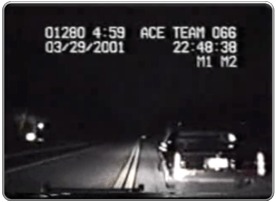

My colleagues at the Cultural Cognition Project have conducted a robust series of experiments, using factorial vignette surveys, which have proven again and again that people’s world views, particularly whether they are authoritarian or communitarian (read–roughly equivalent to the stereotypical American right-vs.-left-winger), significantly shape the way they not only form opinions, but perceive facts. Every year I rely on their excellent experiment involving Scott v. Harris, in which their conservative and progressive respondents differed on their perception of the same car chase video–the former believing that the driver risked the public and the police to the point that the police was right to run him off the road, the latter believing that the police was at least partially, if not wholly, to blame for the outcome. This was not a high school debate; the respondents all viewed, with their own eyes, a grainy but informative six-minute black-and-white video of the chase. But what they viewed and what they saw were two different things, with the latter strongly shaped by their life experiences and values.

No one is immune to these distortions; if biases and heuristics didn’t cloud our rationality, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s work would not have won the Nobel prize. But from the people who present themselves as the party of truth, the antidote to the Trumpian web of lies and fantasies, one expects better.

The issue of false allegations and #believewomen is a classic example. There is factual disagreement, which maps neatly unto political dividing lines, on what percentage of complaints about sexual harassment/assault/abuse are false. The actual percentage is obviously unknown, so our life experiences and values fill it in. Thing is, the progressive side of the map has wrapped its beliefs about this in an issue of virtue. The groupthink is so powerful not just because this is what we believe, but also because anyone who believes otherwise is a bad person. Progressive ideology props itself up by the self righteousness of its devotees. To be deemed a bad person, a person without virtue, is destructive in this milieu. To minimize the very real and understandable distress that people feel at being discredited morally, publicly, via social media as some sort of expression of liberal-centrist privilege or “white tears” is to miss out completely on how oppressive this thought control machine has become, and how even questioning the bon ton can discredit and destroy people’s careers, relationships, and reputations.

There are many harms stemming from this equivalence between factual perceptions and moral virtue. As some have pointed out apropos the Tara Reade business, every false complaint harms the credibility of true complainants. But this story has also brought into crystalline focus the discomfort people feel when they have to backtrack from one of these #believewomen situations that turn out to be unmerited. We already know the truth doesn’t matter anymore. What matters is that now there is plenty out there, circulating around social media and people’s minds, about Joe Biden and rape. What matters is that people with valuable information who might question or discredit unproven allegations have hesitated–and will continue to hesitate–to come forward out of fear of appearing to be bad people, with all the professional and personal implications of lack of virtue that are all too real for progressives. What matters is that our feet are glued into the sticky cesspool of virtue, like flies caught in molasses, and it keeps us from coming to every situation we encounter, particularly those with very high stakes, with a beginner’s mind, ask ourselves, “is it true?” and answer, “I don’t know.”

No comment yet, add your voice below!