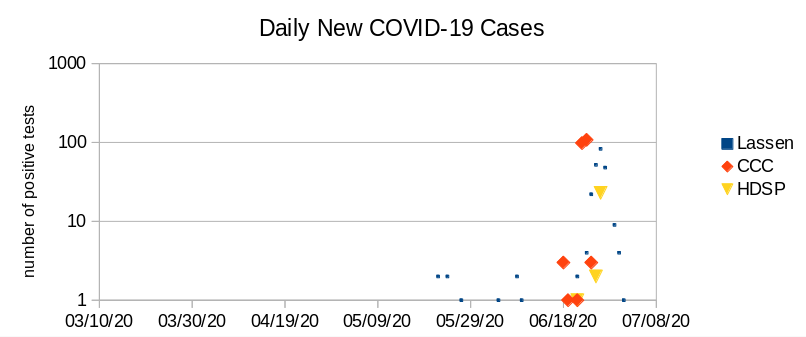

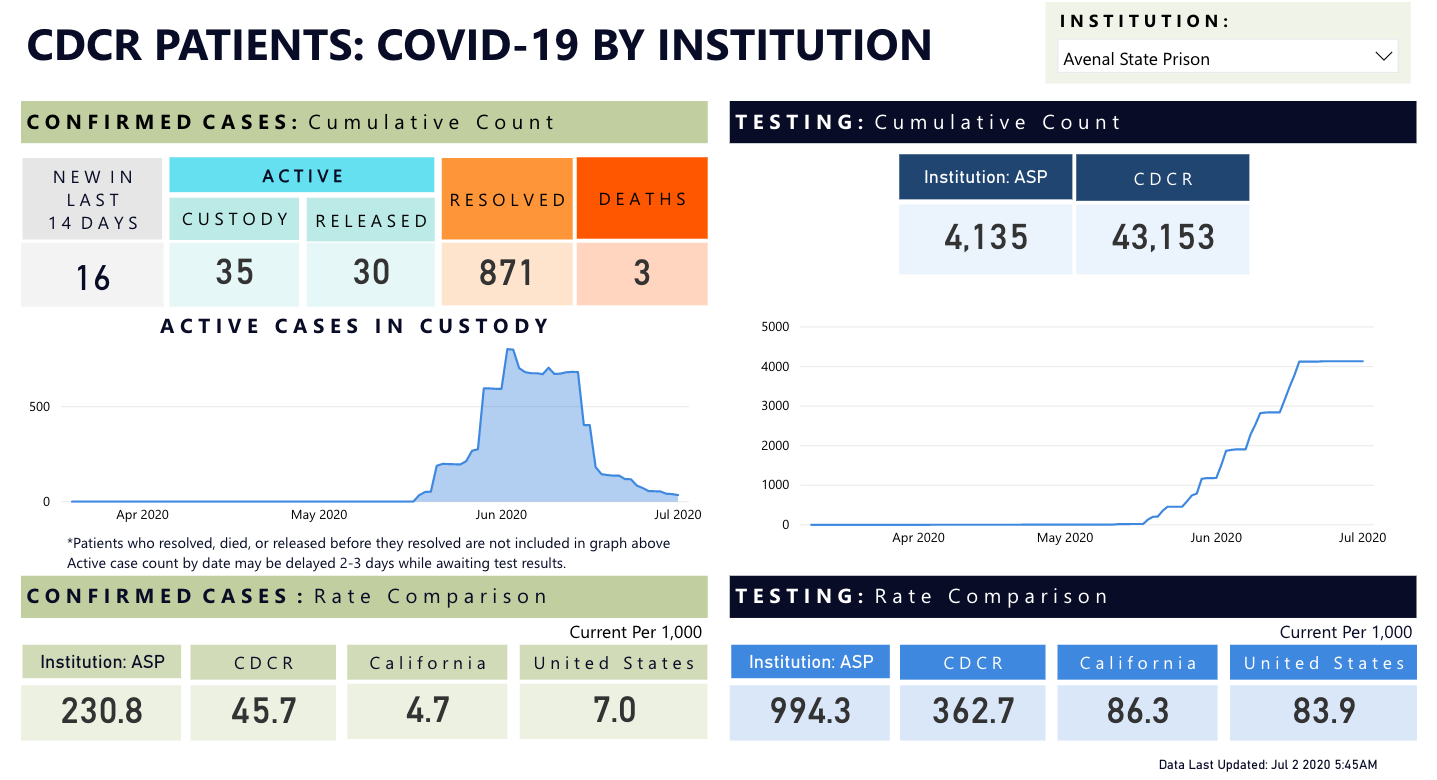

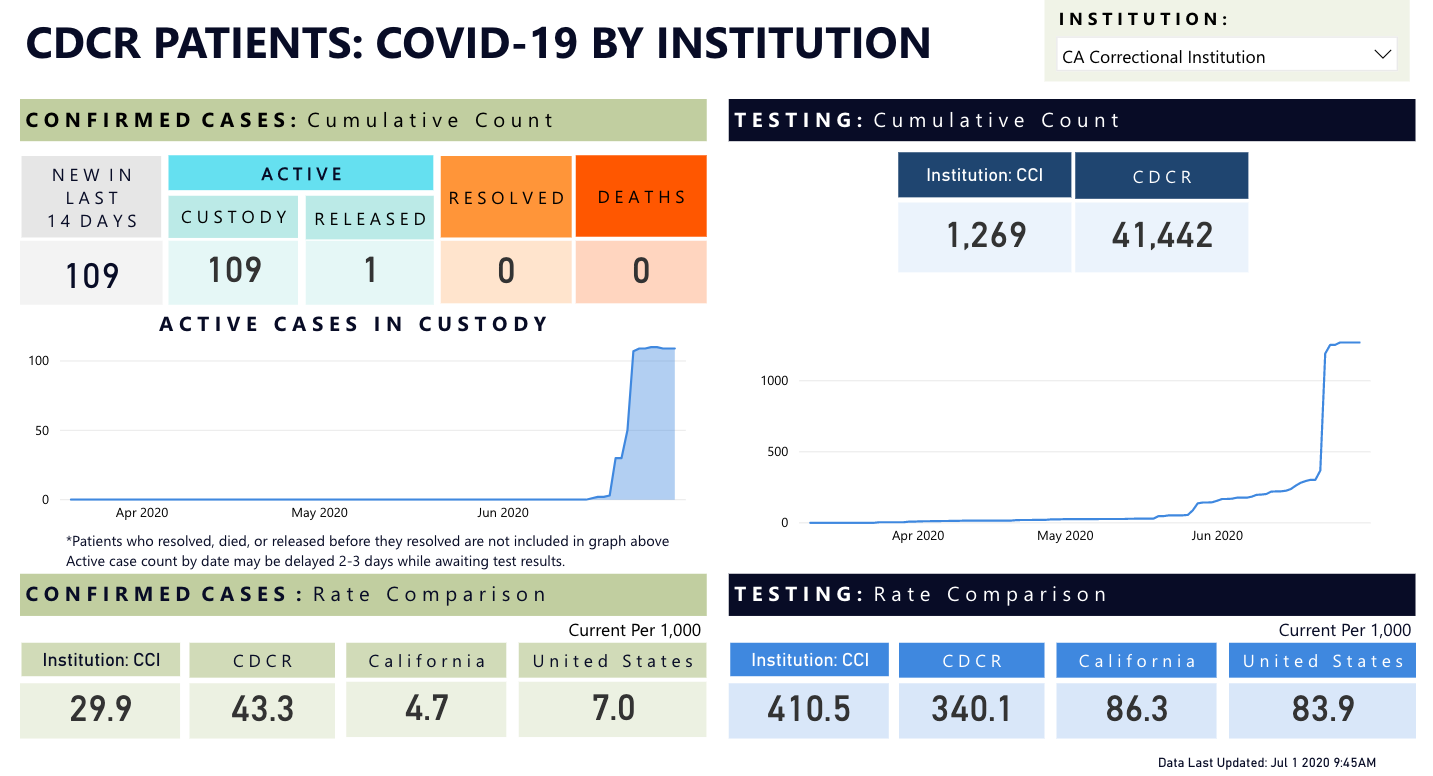

Building on the work we did in the last couple of weeks based on the CDCR COVID-19 tool, my partner Chad Goerzen spent a few days and nights synthesizing the numbers from the tool with the numbers for the surrounding counties from the L.A. Times tool. We think these plots tell stories about the interplay between prison and community infections, but the stories are incomplete because testing (and retesting) is so lacking, so take them with a grain of salt.

Up on top you see our plots for Lassen county prisons and for Lassen county population. Please keep in mind that the L.A. Times ticker does not include prison populations (though it does include residential homes, as per their data page, and we don’t know whether it includes county jails.) As you’ll see, the Lassen plot confirms that the prison and outside community outbreaks happened in tandem, and that we cannot rule out a causal story that explains the spike in Lassen County as an outcome of the botched transfer from Quentin to Lassen. The spike makes more sense if you notice that our Y axis is exponential, not linear.

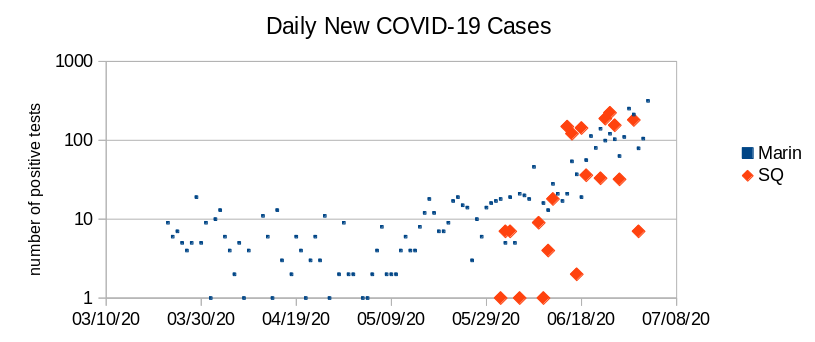

The Marin county plot tells a very similar story. Notice that the outbreak in Quentin slightly preceded the sharp spike in county cases, confirming the theory floated in the Chron a few days ago that attributes the Bay Area spikes in great part to the Quentin outbreak.

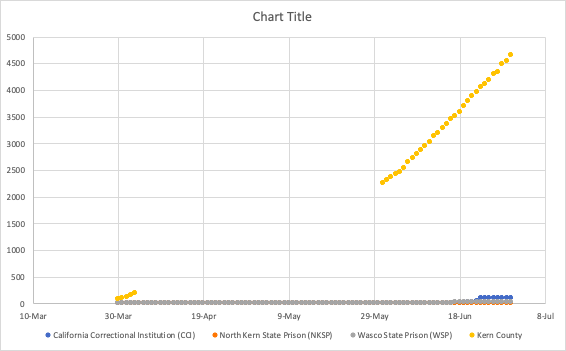

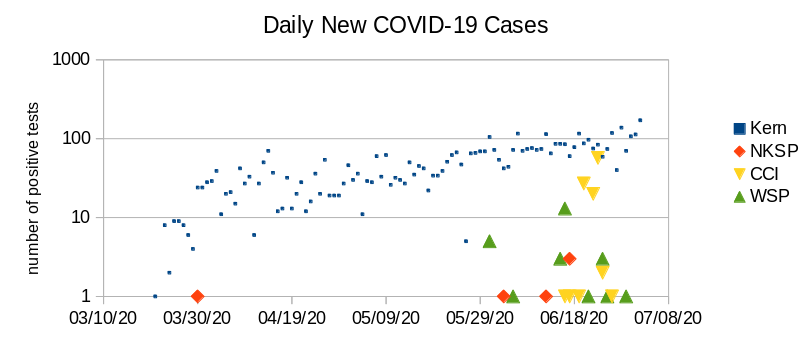

In other counties, it’s more plausible that the prison outbreaks occur either as a consequence of a community contact or some CDCR snafu, against a backdrop of a county that sees exponential increase in new cases (seen in this graph as linear). A classic exam is Kern County, which we looked at a few days ago. Kern is a relatively open county with low levels of shelter-in-place compliance, and it’s not surprising we’re seeing contagion in all three prisons, which is more consistent with a story of surrounding county chaos than a particular transfer to a particular prison.

Seeing a similar pattern in Kings county. You can see a discrete outbreak in the local prison, against a backdrop of rising cases in the neighboring county. We see the county spikes closely following prison spikes (or vice versa; we’re not sure whether the 6-day testing lag in prisons is the same in the counties), but it’s hard to tell a causal story.

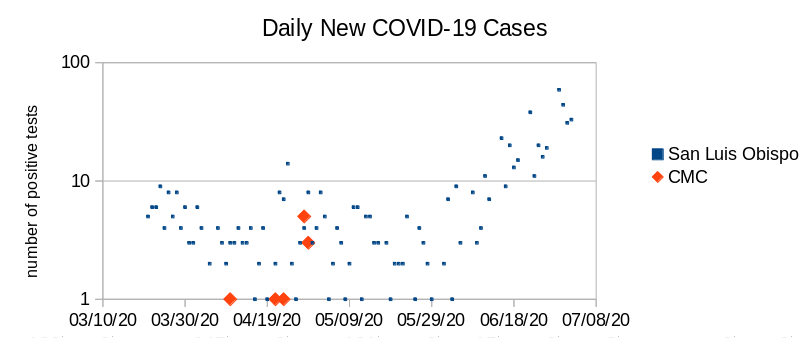

Same thing in San Luis Obispo. We’re seeing the outbreak at CMC against the backdrop of community infections, and it could be attributed to a community contact or to CDCR mismanagement:

At Imperial county, we see parallel outbreaks in prison and county, both of which follow the same pattern over time.

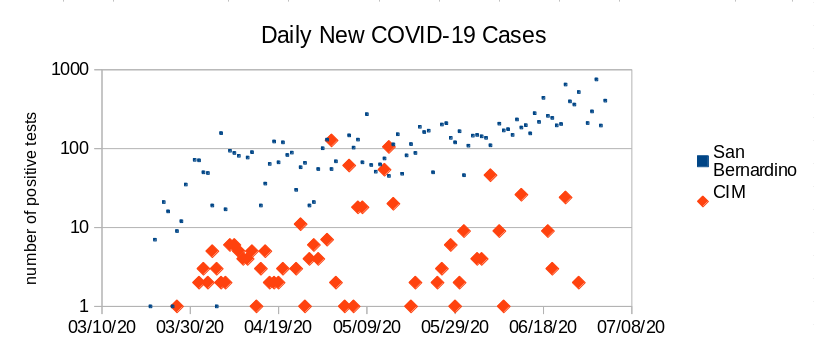

Same deal (with worse numbers) in San Bernardino, where the virus continues unabated in both county and prison:

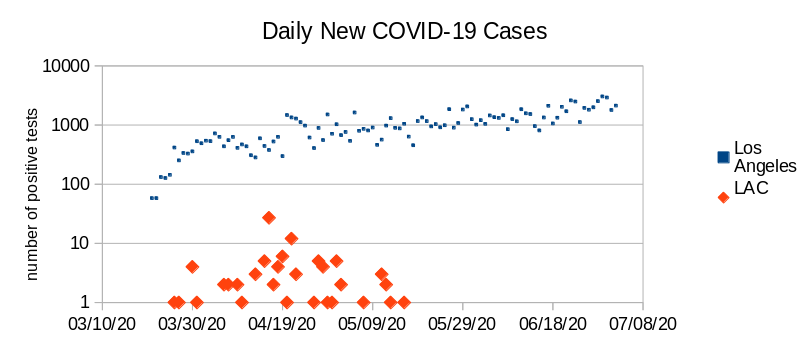

At L.A. County, which has the worst numbers in the state, there was early on a serious outbreak at the local prison, which has now abated, but their jail is facing some serious problems.

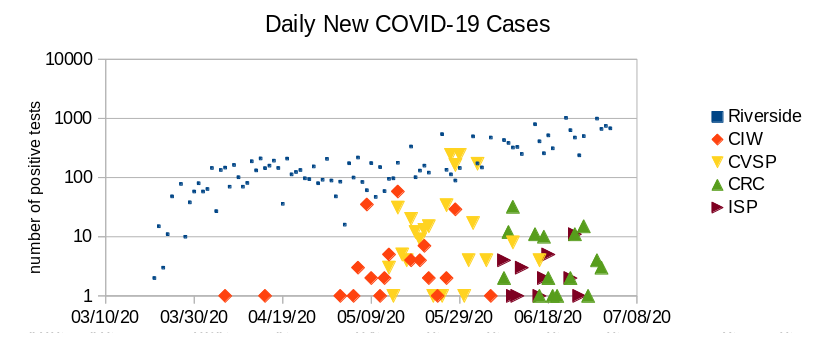

Now take a look at Riverside county, where outbreaks at local prisons are staggered (and all in different stages of abatement.) The county numbers continue to grow–started rising exponentially in mid-May after rising at the same rate since late March — and it’s hard to tell a story about community contacts.

Given the variety of patterns and the low quality of the data, it’s hard to tell a consistent story about this, except the Marin and Lassen stories, which are the most obvious. The only takeaway, which I think is not an unimportant one, is the two-way permeability of prison and county populations. This should provide a rather solid answer to whoever in your life is telling you “but I don’t care about ‘those people'” when you sound the alarm about prison outbreaks.