On my first day of law school, Ruthie Gavison taught us a 1964 case, The AG vs. Bash. In the 1950s and 1960s, it was not uncommon for people to toss old refrigerators in their back yards, and in those days, there was no way to unlatch a refrigerator door from the inside. You can guess how tragedy ensued: children found their way to Bash’s yard, locked themselves in a fridge and died. Bash was convicted of manslaughter and appealed all the way to the Supreme Court. His argument was that many reasonable people did the same thing, so his behavior did not fall beneath the standard expected from the “reasonable man.” The Israel Supreme Court denied him relief: the reasonable man, they said, was not a statistical creature, but a creation of the Court, sometimes behaving better than actual people–in order to use the law (at Bash’s expense) to raise standards of caution and prudence. As Prof. Gavison pithily summarized it, on our very first jurisprudence class, “justice and law are two separate things.”

Ruthie was a formidable person. I admired and feared her throughout law school, even when I worked with her as a teaching and research assistant. When she prepared an assignment for the students, or led us through Socratic inquiries, she was always hundreds of steps ahead, and seemed to have little patience with us for not catching up fast enough. I was under the impression she didn’t know who I was at all, but then she wrote me a gorgeous recommendation letter. It wasn’t effusive, but it showed that she saw me, and I was thrilled; I was young, and being liked was important to me. Which is another reason I admired Prof. Gavison: she did not care at all about what people thought of her. At our Dean’s List reception, she showed up wearing a ratty orange sweater, a white-and-blue striped shirt, sweatpants of an unidentified color, and neon pink sneakers. I will remember that outfit for the rest of my days. It wasn’t gender bending, it wasn’t styled to achieve some sort of androgynous effect–it was just whatever was most convenient to grab from the closet before she left, and it was obvious that, even though it was startling, it was not deliberately curated to startle. I almost fainted from admiration–whaddya mean, a person can live in the world and wear whatever the heck they wanted and not give a fig about how they looked? Prof. Gavison was the first woman I knew whose ego was not embroiled in her looks. She had seemingly gotten all that completely out of the way. The early 1990s were fairly prudish, and I arrived in law school without much awareness that a variety of sexual orientations and presentations was on the menu–these were still considered juicy details that would be whispered behind people’s backs–but Prof. Gavison just lived her life as she pleased. At the time, she had a partner (I think I met her once at their home) and her son, Doron, was 3. I was unclear on the details, but Prof. Gavison just did whatever she thought was best, without apology or embroilment in identity politics or conversations about authenticity. That someone could live like this–do whatever the hell made sense to them without minding anyone else’s opinion–was a revelation to me and had a profound impact on the shaping of my own personal life.

This basic authenticity and utter divestment from bullshit characterized Ruthie’s intellectual legacy, too. When I was still in law school, Prof. Gavison was considered part of the lefty intelligentsia; she founded Israel’s Civil Rights Association (ACRI) and was its chairperson for a long time. Later in life, she took several steps to the right, publicly espousing positions that were far from fashionable in her milieu. But Prof. Gavison was never interested in being fashionable; she didn’t even seem to take pleasure in the identity of a contrarian. The simplistic tropes du jour were like a foreign language to her; she was not on-brand or off-brand–she didn’t have a brand. She just thought deeply about her opinions, formed them, and argued for them, because she believed that was right. There was no lying, obfuscation, linguistic niceties, or any adoption of fashionable terms and tropes to belong or to avoid offending. There was also no deliberate unkindness or petty politicking. If she thought it, she said it. And even if you didn’t agree with it all, it was always memorable.

Perhaps the most important influence that Prof. Gavison’s immense public intellectual career had on my own work was something she said at a criminology conference in Jerusalem in 2000 (I listened to every word because I was doing simultaneous interpretation for two people who would later become my mentors and then my friends, Malcolm Feeley and David Nelken; they were visiting Israel and attended the conference.) We were talking about victimology and victims’ rights, and everyone was bending over backwards to acknowledge suffering and hardship and grief. Prof. Gavison took the podium, and said, “the first and foremost thing that is owed to victims is that they stop being victims as quickly as possible.” This struck me like lightning, because even twenty years ago, before the current obsession with positionality and personal biographies, victimization as an identity mattered a lot, especially in the context of casualties of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. To stand on a podium and say plainly, without meanness but without polite caveats, either, that clinging to victimization was not the way to go, was revolutionary and brave. She got skewered for comments like this later in life, as heralds of #metoo permeated public discourse and social media became “a thing”, and her comments about self sufficiency and moving on were taken as victim-blaming. But she was never unkind or disdainful. Her recent post against overcriminalization in sex offenses is the epitome of genuine compassion–truly caring about people’s best interests without weaponizing or infantilizing them or turning them into a morality tale. For her, it wasn’t about blame; it was about what made the most sense, and if anyone wanted to take it personally or make political capital off of victims or perpetrators, that was their problem.

I probably would never have written Yesterday’s Monsters if I hadn’t been raised, intellectually, by Prof. Gavison. It is a difficult moral and personal hurdle, to speak or write publicly against the hagiography of victims, especially vocal victims of a heinous, high-profile crime. It takes guts, and I’m not as blasé as Prof. Gavison was about people’s reactions to my work. While I was working on the book, I agonized over whether I was overly harsh on the Tates. It has never been my intent to hurt victims, as it has never been Prof. Gavison’s intent to do so, but causing them anguish was not a consequence I could discount. Moreover, there was the concern that any call for compassion involving the Manson family would fall on deaf ears and draw fire for the worst reasons. Mean comments or one-starred reviews on Amazon from people who sanctify victims as the unquestioned owners of retributive discourse were always a possibility. When I was publicly speaking in support of death penalty abolition, I caught a lot of flak, including death threats, from people on this (the irony of threatening a murder while arguing for capital punishment for murderers was obviously lost.) But Prof. Gavison had taught me to look at the bigger picture. Having one’s life upended by violent crime is not a choice people make, and people will feel about it however they will feel. Their feelings are their feelings. They are valid by virtue of being part and parcel of the human experience, and they are in each of us. But it does not directly follow that public policy should enshrine these feelings as the be-all, end-all of morality, and it does not follow that the best way to honor these emotions and give them room is the criminal process. The acknowledgment that people are who they are, and that one’s policy suggestions need not coddle nor confront their basic way of being, is something I’m still learning. But as I age, I care a lot less what people think, and I see through performative games quickly enough to get to the point.

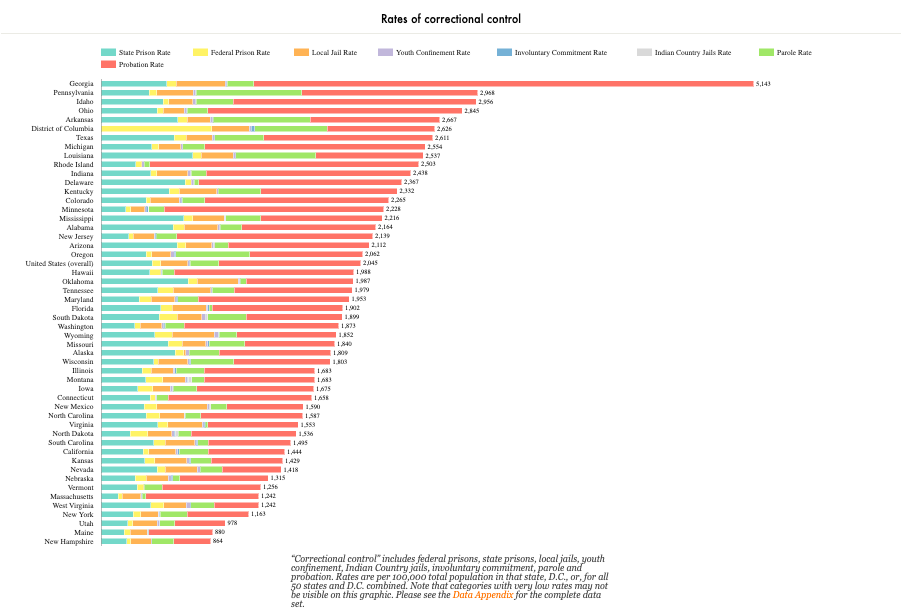

I got the news of Ruthie’s passing shortly after reading Jason Fagone’s phenomenal article in the Chron yesterday, in which he unflinchingly looks at the numbers and offers a practical roadmap to cutting half of California’s prison population. This is the first time I’ve seen a mainstream newspaper treat this eminently sensible policy suggestion seriously, and rather than present it as some sort of radical idea, wrapped in a lot of “dismantle” and “defund” and “abolish” lingo, chart a roadmap illuminated by decades of robust empirical work. It’s not nuts. It’s the way to guarantee minimal standards of care without putting public safety in peril. One of the commenters (I couldn’t resist) said something like, “next thing they’ll suggest releasing the Manson family.” It’s to Prof. Gavison’s credit that, as her student, I read this, shrugged, and thought, “funny they should mention that.” Ruthie taught me jurisprudence, law and society, and law and politics, but the most important thing she taught me was that grownups should not be afraid of monsters.

Prof. Gavison was, and will always be, a shining beacon of authenticity and truthfulness. It deeply saddens me that we have lost her clear, courageous voice, when such voices are so essential. What is remembered, lives.