On July 9, 2020, the #StopSanQuentinOutbreak coalition held a press conference outside the prison gate to draw attention to the medical crisis behind bars. The five weeks that preceded the conference saw the COVID-19 case count in the facility grow from zero to more than a thousand, and when we held the conference, people were already dying. Many people spoke at the conference–family members, formerly incarcerated people, doctors, experts, politicians.

The picture above is from the press conference. On the right side of the picture is then-Assemblymember Rob Bonta, who spoke very movingly and urgently about the need to have Gov. Newsom visit the prison and release people. Bonta’s speech was quoted in the Guardian:

“We are in the middle of a humanitarian crisis that was created and wholly avoidable,” said the California assembly member Rob Bonta at a press conference in front of San Quentin state prison on Thursday.

“We need act with urgency fueled by compassion,” he added. “We missed the opportunity to prevent, so now we have to make things right.”

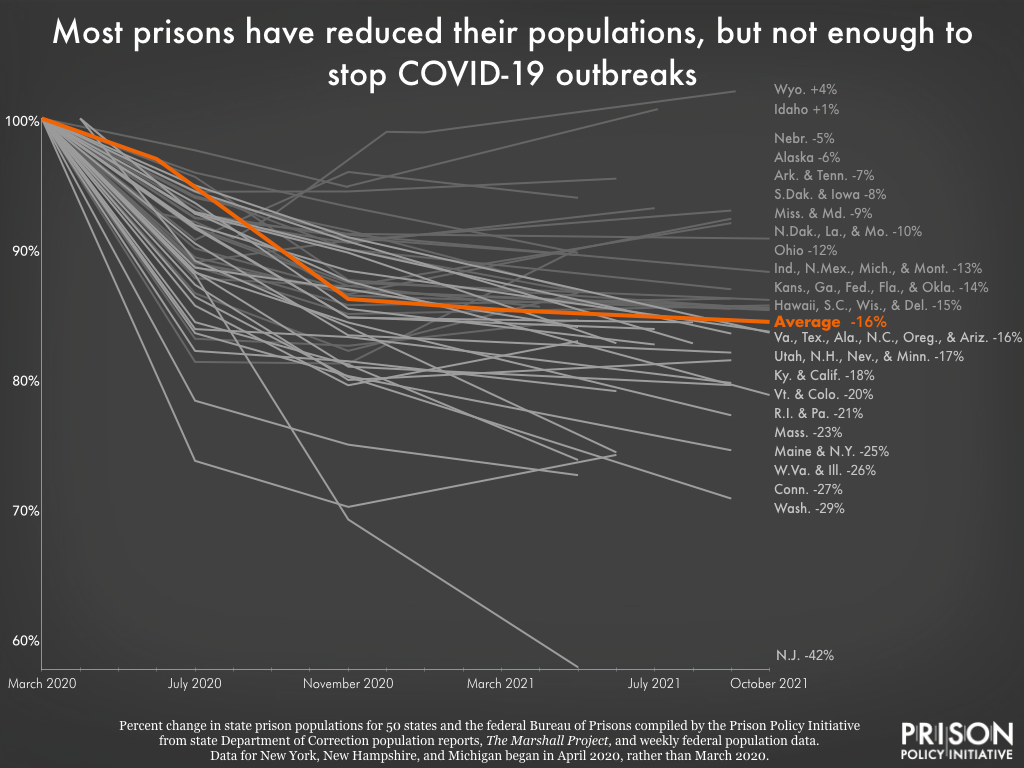

Fast-forward a year and a half, and Bonta, now California’s Attorney General, is appealing Judge Tigar’s order to vaccinate the guards in CA prisons. The staunch resistance at CDCR and at the Governor’s mansion to the idea of letting old, sick people be released back to their families–purely for optics reasons, as they pose little to no risk to public safety–resulted in a paltry an ineffectual release policy (as I predicted the day it was announced) and, also predictably, in a complete abandonment of the release plan as soon as vaccination emerged on the horizon. Within the activist/advocate community, this presented a problem: while vaccines would slow down, or even end, the COVID-19 crisis, they would not prevent future contagions, which are sure to come given the prison infrastructure, medical understaffing, and chronic neglect and indifference. At the time, when talking to a friend, I said we had to get on the vaccine bandwagon; the fight to save lives now was as important as the fight to save more lives in future years, and we certainly could not afford to let go of the call to make the prison population a top vaccination priority.

Despite some governmental hiccups, and despite the prevalence of ignorant arguments that combined deservedness with medical care, people in correctional facilities educated themselves about the benefits of vaccination and, thankfully, accepted the vaccine at rates exceeding the general population. The credit for this success goes first and foremost to the correctional residents themselves, who had to sift their way through mountains of disinformation from custodial staff and their own mistrust of anything coming out of the authority that caused the outbreak in the first place. It also goes to formerly incarcerated people who encouraged their friends to do the right thing, and to AMEND for targeting correctional populations with excellent, 100% reliable medical advice. It certainly does not go to the government, which deprioritized prisons throughout the process.

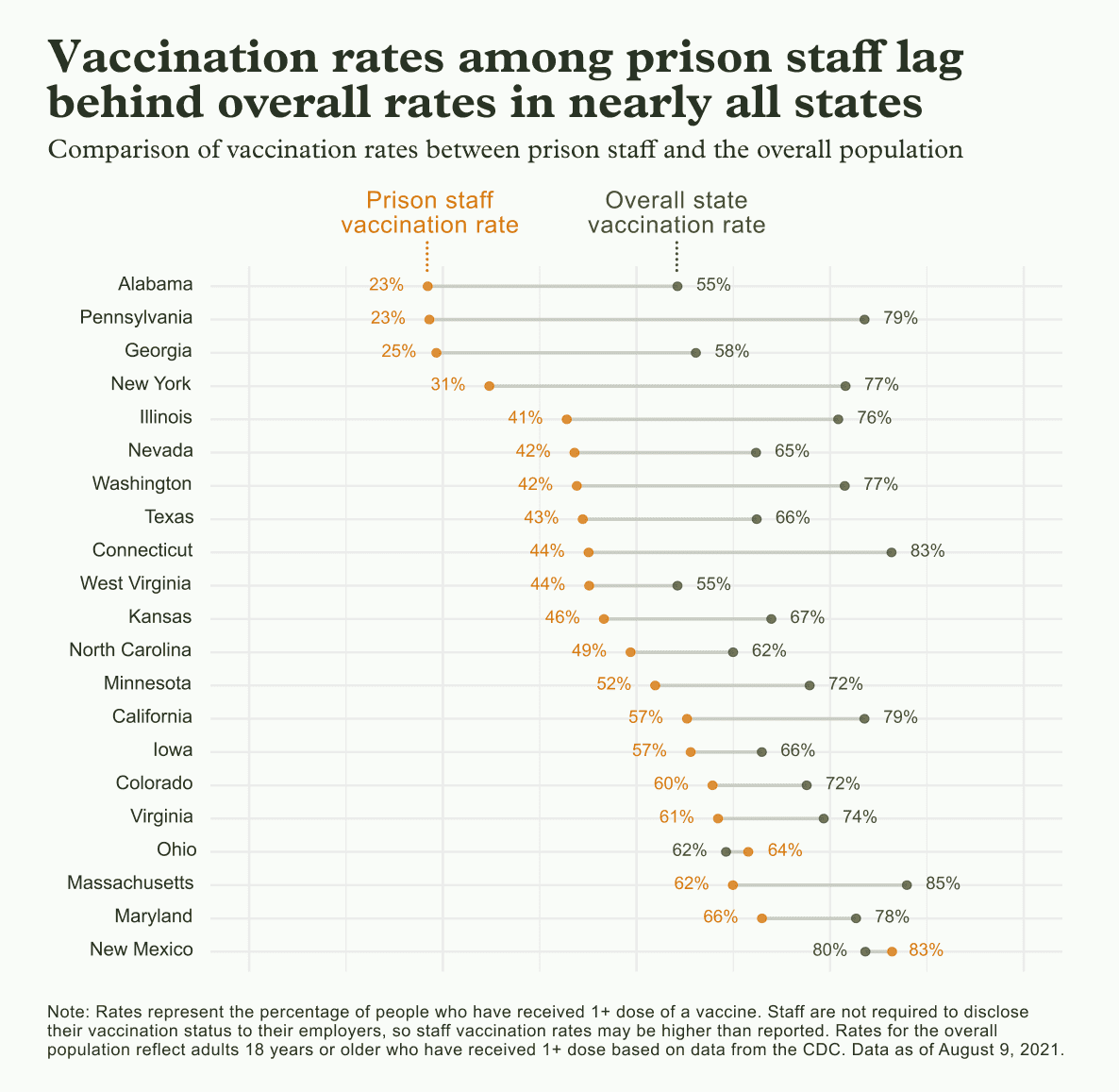

More seriously, the staff is still the problem: custodial staff nationwide are still refusing vaccines at mind-boggling rates.

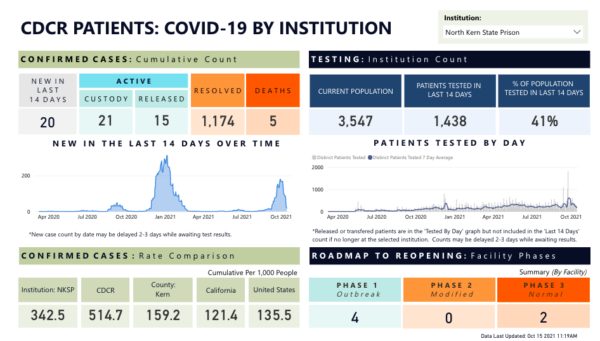

In short: Even though the fight to release people is still as urgent and relevant as it was in the summer of 2020, virtually nothing has happened on that front that would make a difference during this pandemic or the next one. Jail populations are back up to pre-pandemic levels; California prisons, which are still overcrowded despite a 18% population reduction, are now responsible for 7 out of the top 10 largest COVID-19 prison clusters in the country.

Against this backdrop–the most important and pressing measure for contagion prevention basically abandoned–the litigation battle lines have been drawn at a much more modest expectation: staff vaccination. As a legislator, Bonta called for the more thorough system fix; as part of the Newsom administration, his employees are defending indefensible arguments and making absurd excuses to shirk responsibility even for the truly modest goal of protecting the lives of staff and incarcerated people.

Bonta/Newsom’s zealous appeal against this modest goal (essentially an incomprehensible support of Trumpist anti-vaccine drivel coming out of the Proud Heroes of the Resistance! or is it?) is even more absurd when compared to the Newsom/Bonta perspective on mandating vaccines in schools, considerably less dangerous settings than correctional facilities from an epidemiological standpoint. Indeed, some anti-maskers are calling Newsom/Bonta to task for forcing them and their kids to vaccinate when they are not imposing such duties in prison (even a broken clock shows the correct time twice a day.) Bonta’s response when a CalMatters journalist confronted him with the hypocrisy? “I have a client” (i.e., CDCR) and “you’ll have to take it up with my client.”

Which brings up an important question: What, actually, is the Attorney General’s job? Is the AG wearing two separate hats when supporting legislation/regulation and when litigating? Can the government speak out of two sides of its mouth on, essentially, the same matter of scientific/medical validity? When litigating in court, is the AG no more than a hired gun for a “client” (the government) with no obligations to support what’s right? Does the AG stop working for us when he works for our government? When protecting anti-masker prison guards, does the AG stop being a public official, holding office for the benefit of all Californians, and become CCPOA’s Tom Hagen?

Here are two instructive scenarios from recent CA history. In the first one, then-Governor Jerry Brown and then-AG Kamala Harris were called upon to defend a new amendment to the CA constitution, otherwise known as Prop 8 (“marriage is between one man and one woman”). You may recall their position then: Harris declined to defend Prop 8 “because it violate[d] the Constitution. The Supreme Court has described marriage as a fundamental right 14 times since 1888. The time has come for this right to be afforded to every citizen.”

Let’s recap: The Eighth Amendment guarantees freedom from cruel and unusual punishment, which in the context of prison conditions means that deliberate indifference to a serious health and safety risk is violative of the Constitution. We now have a ruling that having unvaccinated staff at CDCR facilities is a violation of the Eighth Amendment. AG Bonta, why would you defend this in federal court?

In the other instructive scenario, Harris, again as Attorney General, appealed Jones v. Chappell, a federal court decision that held the death penalty unconstitutional because of the delays. At the Ninth Circuit, they prevailed on a narrow, technical ground–the district court had applied a “new rule” at a habeas proceeding (for my explanation of this technical legal point, see here.) On principle, I still maintain that it was wrong of Harris to appeal the decision (here‘s a summary of my position on that matter.) It was an illustration of a tail-wagging-the-dog scenario: Harris walked away from that incident remembered for upholding a technical retroactivity ruling, rather than for dismantling our dysfunctional and monstrous death penalty. But at least there was some doctrinal support for that position.

This is not the case here: we have a ruling that is not only correct (and extremely narrow) on a policy level, but also on a legal level. Bonta and Newsom know full well that their position is morally and legally indefensible. Why, then, are they appealing, and is this a fulfillment of the AG’s ethical obligations?

Moreover, even accepting Bonta’s peculiar distinction between his role in legislation and in “client” representation, even the most zealous and unprincipled gun-for-hire private attorney will have situations in which it will be necessary to sit down with the client and explain that a position that the latter wants to advance in court is untenable (e.g., there’s no hope for an insanity defense because the defendant is sane; there’s no self-defense because there’s ample proof that the defendant shot someone in the back for profit with no provocation whatsoever.) In situations in which the client insists on a particular line of legal argumentation, lawyers who cannot pursue that line with a straight face need to withdraw from representation. It is long past time for Bonta and his employees to have a come-to-Jesus conversation with their “clients” and explain that vaccinating the staff is a minimal, modest expectation, barely enough to pass the already eroded Eighth Amendment standard, and that balking at it is not a move that the AG’s office can support.