For the first time since Fall 2019, I got on a plane on Monday and flew to New Orleans; Professor Adam Feibelman very graciously invited me to participate in the Workshop on Law and the Economy, and I had the opportunity to present Fester to people who read big chunks of it, including the introduction and Chapter 4. Having recently presented Chapter 6 at Case Western, I’m pleased that the book is beginning to take shape, but I still feel that the story is unfinished.

Part of this feeling comes from my bitter disagreement with Judge Howard’s final ruling in our San Quentin cases, according to which relief is moot because the vaccines “changed the game.” A recent study conducted at a federal prison involved daily testing of vaccinated and unvaccinated residents. It’s a rather small study – 95 participants, 78 vaccinated and 17 not fully vaccinated – but it disturbingly found “[no] significant differences. . . in duration of RT-PCR positivity among fully vaccinated participants (median: 13 days) versus those not fully vaccinated (median: 13 days; p=0.50), or in duration of culture positivity (medians: 5 days and 5 days; p=0.29)”, though “[a]mong fully vaccinated participants, overall duration of culture positivity was shorter among Moderna vaccine recipients versus Pfizer (p=0.048) or Janssen (p=0.003) vaccine recipients.” Since we know this is not the case outside prisons–and with the obvious caution that the study was small and limited in time–we can’t say anything resolutely except feeling some unpleasant doubt about vaccination as the be-all, end-all strategy of contagion prevention in enclosed spaces. It is important and vital, and at the same time, only one piece of the distancing/masking puzzle that curbs infections. This is particularly important with the advent of the Omicron variant, which is already prompting travel bans and ravaging the economy. If Delta is anything to go by, we should be seeing Omicron cases pop up behind bars before too long.

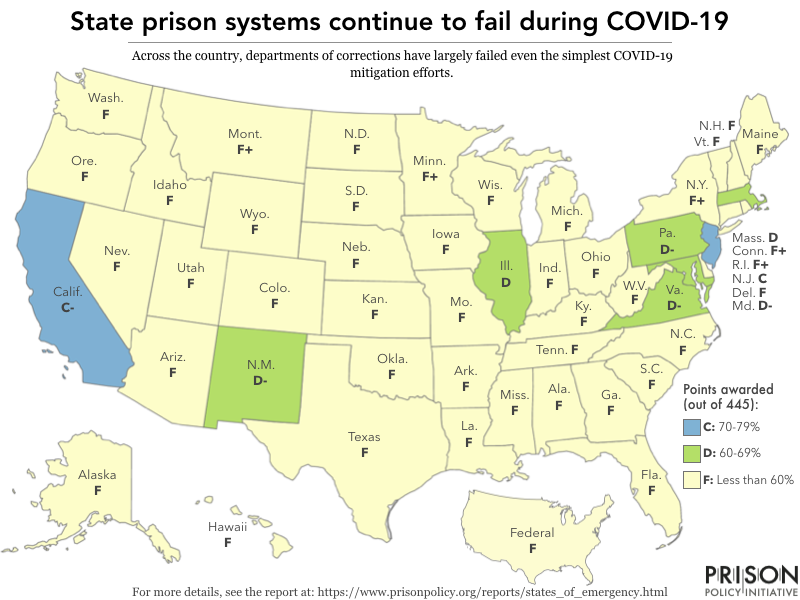

Another reason I feel the FESTER story is unfinished is that I’ve been focusing solely on California in my own work, and it is only now that I’m seeing how the catastrophe of neglect and indifference that played out here is not the absolute bottom. Prison Policy Initiative recently published States of Emergency, wherein they grade the states based on their prison pandemic performance using a multifactor index comprised of population reduction (up to 130 points), infection and death rates (up to 145 points), vaccination efforts (up to 115 points) and basic policy changes to address needs, such as free phone and video calls, masks, and hygiene products (like soap), required masks for staff and mandated regular staff testing, and eliminated medical co-pays. (maximum 115 points). Amazingly, California gets a C-, putting our state at the top of prevention efforts, while most states get an F.

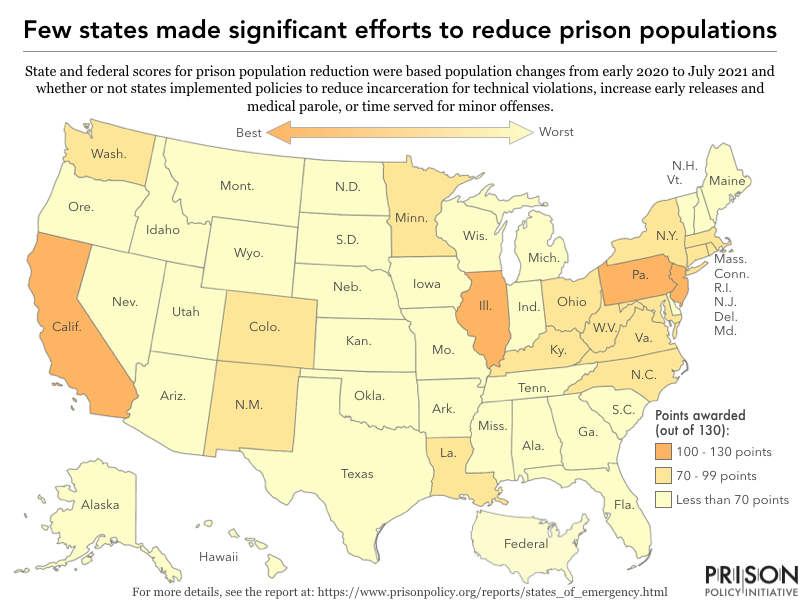

Even more amazingly, the report places us at the top in the category of population reduction, despite the fact that the summer releases involved a “push out the door” to people nearing the end of their sentences, excluded precisely the high-risk people who were most in need of protection, and created no more than a temporary population dip that has now been completely eclipsed.

You can see in the bottom graph why I find these high marks puzzling. First of all, please keep in mind that the Y-axis in this graph is not zero, which would put the summer dip, that looks huge in this graph, in stark perspective. More importantly, note that we are, again, at over 100% capacity, just as the Omicron variant knocks on our door and current outbreaks are already registered in several CA prisons and jails.

It was interesting to talk about this at Tulane, because Louisiana prisons and jails are notorious; friends of mine are uncovering in-custody deaths and fighting against inhumane treatment of people with disabilities behind bars. What I wanted folks to take away from our conversation was that red states have not cornered the market on myopic frameworks driven by quarantinism and by the myth of carceral impermeability. We had a great conversation and I enjoyed my visit.

The logistics of my trip were complicated by a serious and upsetting foot injury; I’m training for the Oakland Marathon and, 9.5 miles into an 11-mile practice run, I tripped and badly sprained my ankle to the point that I can’t put weight on it. If nothing else, the experience taught me is that, much like the Zen koan about the tree, if a person falls to the ground in excruciating pain in Glen Canyon and screams at the top of her lungs, absolutely nothing happens, and the person has to somehow crawl on hands and knees for twenty minutes to get out of the forest and seek help. This has thrown doubt not only on my ability to recover in time to safely train and complete the marathon, but also on my multisport fitness regime in general; whaddya know, it turns out one uses one’s ankles quite a bit when swimming and cycling. I’ve managed to figure out a way to start and stop my bicycle while wearing my immobilizing boot, but it feels a bit scary and unsafe to be out there cycling with this vulnerability, and having three energetic little ones (one human, two felines) at home bouncing around my limbs is warming my heart but making feel brittle and guarded.

As is always the case when traveling, I learned lots of interesting things that have nothing to do with work. I talked to business owners about their tentative plans for Mardi Gras and discovered that, throughout the year and a half that we taught online at Hastings, Tulane held class in person (!!!) by implementing an aggressive testing regime and renting rooms at empty downtown hotels to quarantine students who tested positive at the university’s expense. Ah, what an excellent epidemiology department and a grand endowment can do! But even if we had such resources at Hastings, I think the politics of pandemic management in California (the sanitationist part, anyway) would have impeded us from holding classes in person. And I’m also sure that what looks now, in hindsight, like a great triumph at Tulane (and rightly so), must’ve felt uncertain and stress-inducing to students, staff, and faculty alike.

I also got to hear some jazz, eat extremely well, see a wonderful exhibition at the Newcomb Art Museum, and hobble around the French Quarter in my immobilized boot. I’m very grateful to my gracious hosts and to the students, who wrote interesting and provocative response papers about FESTER that I’m sure will be useful as I gear up toward a winter of aggressive progress on the manuscript draft.

No comment yet, add your voice below!