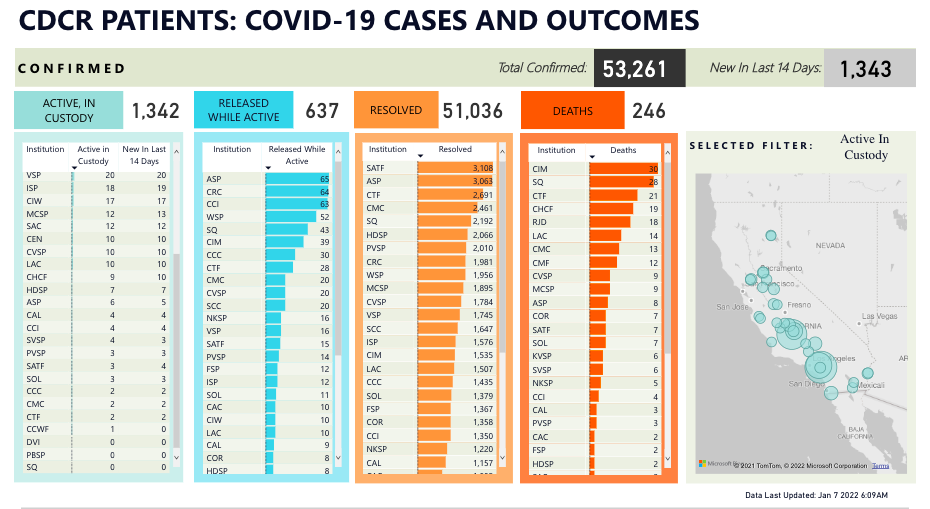

At first glance, today’s COVID-19 numbers for California prisons appear to be a grim reprise of the two previous outbreak waves: thousands of cases, with major outbreaks in several facilities. Clearly, we have learned nothing from the last two years, which led to infections among more than half of the prison population and to 246 deaths; Governor Newsom’s recent reversal of 80-year-old Sirhan Sirhan’s parole bid indicates that politics and optics, rather than pragmatic public health and public safety considerations, are standing in the way of sensible choices. But upon closer inspection, this third wave features another cause for alarm: in addition to the 4,069 active cases among incarcerated people, there are currently 4,570 active cases among prison staff, and in 20 prisons, more than 100 staff members are currently infected.

The reason is not particularly mysterious. Throughout the last two years, California’s prison guards’ union (the CCPOA) led a dogged fight against mandatory vaccination for its members. For many months, the federal district court hearing the case adopted a conciliatory, welcoming approach, appeasing the guards and turning to gentle persuasion methods; these have proven useless in raising the vaccination rates among the staff. Finally, after the COVID catastrophe ravaged prisons (and several months too late to save lives) Judge Tigar ordered a vaccine mandate; the guards, the prison authorities, and Governor Newsom are opposing the mandate and their appeal is pending before the Ninth Circuit.

Whether prison guards refuse to get vaccinated due to indifference, COVID-19 denialism, or misguided politicization of healthcare, is pure speculation. But in their appeal, opponents of the mandate raise concerns that requiring vaccinations might lead to mass resignations of prison guards, which in turn would result in understaffed prisons. This scenario was feared, but failed to realize, in many other employment sectors with mandates, where vocal protestations and threats of resignation gave way to vaccination compliance. Indeed, the opponents’ stance is generating precisely the scenario they worry about: it turns out that, when thousands of people are sick at home, prisons become understaffed.

The irony of the situation might be completely lost on prison authorities, but it has an even darker side. Even if the threat of correctional officers’ resignations were real, and graver than the very real understaffing generated by the spike in staff cases, we must ask ourselves why courts and government officials so stubbornly cling to the idea of overcrowded prisons as a public good. If it is impossible to hire and retain correctional staff who can provide a standard of care that complies with minimal Eighth Amendment requirements, then it is impossible to incarcerate as many people as we do. We must reckon with the fact that we cannot, lawfully and constitutionally, house, clothe, and feed more than 100,000 people—a quarter of whom are over 50 years old—if the staff entrusted with their care cannot be bothered to take minimal precautions to protect their captive wards from disease.