This morning at the Western Society of Criminology Annual Meeting I’ll present Chapter 6 of our upcoming book FESTER, which I’ve tentatively titled The House Always Wins. In this chapter we show how, in both federal and state litigation for COVID-19 healthcare, prison authorities and the guards’ union run jurisdictional circles around the prisoners and their advocates, playing forum battles and jurisdictional whack-a-mole. This morning brought in its wings a fresh example of the same situation: on February 1, Judge Tigar (who also presides over the COVID class action Plata v. Newsom) granted the current and former federal receivers of the prison healthcare system (Clark Kelso and Robert Sillen) a motion to dismiss a class action involving the valley fever outbreak of the mid-2000s. Sillen was appointed Receiver on February 14, 2006, effective April 17, 2006, and was fired by Judge Henderson after two years (it later turned out that Sillen and his employees were overpaid to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars.) Kelso was appointed his successor on January 23, 2008, effectively immediately, and is still occupying that position.

The installment of the receivership created an uneasy division of labor between CDCR–a state department–and the federally-appointed Receiver, who was now vested with the authority to oversee and manage healthcare in prisons as well as with the powers of an officer of the (federal) court. Here is what happened next, which Judge Tigar quotes directly from the Ninth Circuit decision:

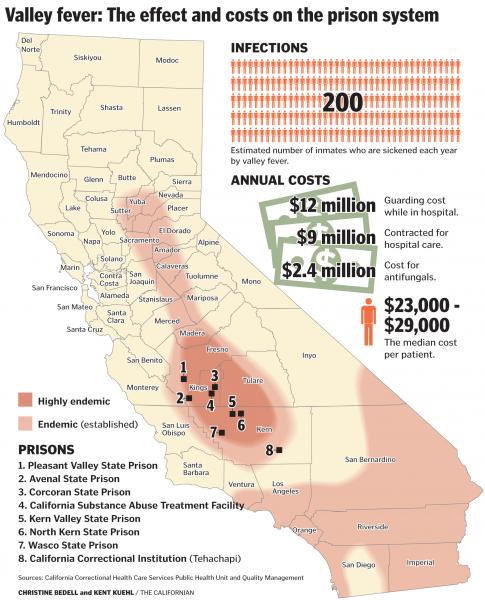

In 2005, California prison officials noticed a “significant increase” in the number of Valley Fever cases among prisoners. The federal Receiver asked the California Department of Health Services to investigate the outbreak at Pleasant Valley State Prison, the prison with the highest infection rate. After its investigation, the Department of Health Services issued a report in January 2007. It stated that Pleasant Valley State Prison had 166 Valley Fever infections in 2005, including 29 hospitalizations and four deaths. The infection rate inside the prison was 38 times higher than in the nearby town and 600 times higher than in the surrounding county. According to the report, “the risk for extrapulmonary complications [was] increased for persons of African or Filipino descent, but the risk [was] even higher for heavily immunosuppressed patients.” The report then explained that physically removing heavily immunosuppressed patients from the affected area “would be the most effective method to decrease risk.” The report also recommended ways to reduce the amount of dust at the prisons. After receiving the health department’s recommendations, the Receiver convened its own committee. In June 2007, the Receiver’s committee made recommendations that were similar to those from the health department.

In response, a statewide exclusion policy went into effect in November 2007. The inmates who were “most susceptible to developing severe or disseminated cocci” would be moved from prisons in the Central Valley or not housed there in the first place. The prisons used six clinical criteria to identify which inmates were most likely to die from Valley Fever: “(a) All identified HIV infected inmate patients; (b) History of lymphoma; (c) Status post solid organ transplant; (d) Chronic inmmunosuppressive [sic] therapy (e.g. severe rheumatoid arthritis); (e) Moderate to severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) requiring ongoing intermittent or continuous oxygen therapy; and Inmate-patients with cancer on chemotherapy.” Inmates were not excluded from the Central Valley prisons based on race. The Receiver refined the exclusion policy in 2010 and created a list of “inmates who [were] at institutions within the Valley Fever hyperendemic area that [needed] to be transferred out.” The record does not indicate that the 2010 policy excluded inmates from the outbreak prisons based on race.

In April 2012, the prison system’s own healthcare services released a report examining Valley Fever in prisons. The report concluded that despite the “education of staff and inmates” and the “exclusion of immunocompromised inmates,” there had been “no decrease in cocci rates.” The authors found that Pleasant Valley State Prison inmates were still much more likely to contract Valley Fever than citizens of the surrounding county. From 2006 to 2010, 7.01% of inmates at Pleasant Valley State Prison and 1.33% of inmates at Avenal State Prison were infected. By comparison, the highest countywide infection rate was 0.135%, and the statewide rate was just 0.007%. From 2006 to 2011, 36 inmates in the Central Valley prisons died from Valley Fever. Prison healthcare services also found that male African-American inmates were twice as likely to die as other inmates. Each year, about 29% of the male inmates in California are African-American, but 50% of the inmates who developed disseminated cocci between 2010 and 2012 were African-American, and 71% of the inmates who died from Valley Fever between 2006 and 2011 were African-American.

Following this report, the Receiver issued another exclusion policy –one that would effectively suspend the transfer of African-American and diabetic inmates to the Central Valley prisons. The state objected, but the district court ordered the prisons to comply with the new exclusion policy.

Hines v. Youseff, 914 F.3d 1218, 1224-25 (9th Cir. 2019)

In Hines, incarcerated people infected with valley fever attempted to sue CDCR officials for mismanaging the outbreak; the lawsuit failed due to qualified immunity. The officials prevailed because they followed the orders of the Receiver. This week’s decision dismissed a similar lawsuit against the Receiver.

The valley fever victims argued, on the merits, that the Receivers were neglectful in their preventative approach; the Receivers countered that, as officers of the court, they have quasi-judicial immunity. The plaintiffs attempted a sophisticated attack on this argument, claiming that the Receivers should not have directed CDCR’s preventative policies, and that their mandate was limited to providing medical care. The argument failed: Judge Tigar found that “prevention of disease is, and always has been, within the Receivers’ jurisdiction.”

Ironically, it is precisely this wide mandate that aided the Receivers’ success in dismissing the case. Because they were acting within their authority, writes Judge Tigar, and because said authority is quasi judicial, they can enjoy immunity. Weirdly, “Plaintiffs do not argue that the other exception to judicial immunity – for actions “not taken in the judge’s judicial capacity” – applies here”—I think that’s precisely what I would have argued in this case, as Sillen and Kelso were acting as medical officials rather than judicial ones.

If this seems overly technical, it’s because it is. As I observe in chapter 6 of FESTER (more to come on that in the next few days), the particular gymnastics of each courtroom failure are less important (albeit technically interesting.) What’s important to observe is that the Byzantine nature of California’s correctional healthcare system, which, ironically, stems from the effort to create patchwork remedies for the system’s own ineptitude, then stands in the way of recourse for this very ineptitude.

***

Hat tip to Allison Villegas, who sent me this decision.

No comment yet, add your voice below!