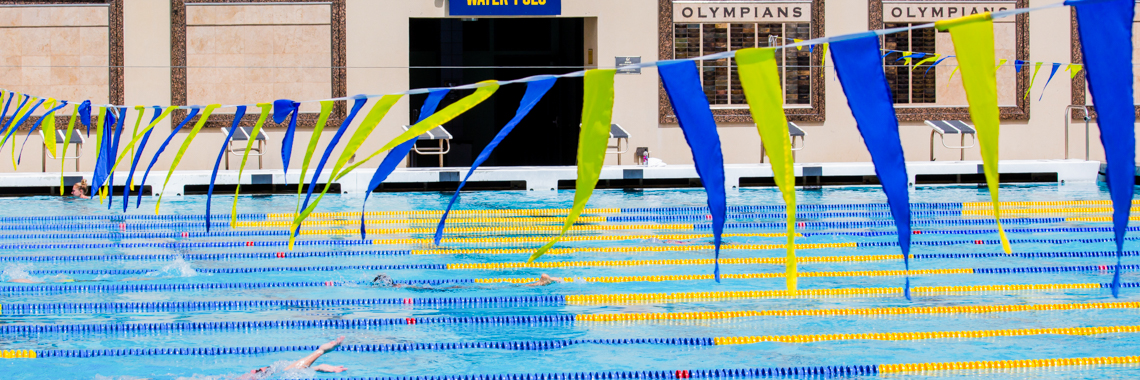

This spring brought in its wings a mountain of work: in addition to my full-time Hastings position, I guest-taught across the bridge at my alma mater, UC Berkeley. I accepted the overload job for various reasons, financial and others, but in addition to the academic joys of being near many old friends (and especially my beloved and admired mentor) and resuming old professional conversations that I enjoy, there were immense athletic joys: every day I was there, after class and office hours, I would revisit my old stomping (splashing?) grounds and swim a good workout on campus. With my favorite facility, Hearst Pool, closed, I sometimes swam in the gorgeous Golden Bear pool, surrounded by a forest and almost always empty, but most of the time I swam at Spieker Pool, the enormous Olympic-sized facility that is home to Cal’s celebrated swimming and diving teams. Oftentimes over the years, when I swam there, the Cal women’s team would be training in adjacent lanes; I was starstruck by all the fantastic athletes I cheered during Olympic games and world championships and concluded that, if I was managing one lap to every two of Missy Franklin’s, then I was not too shabby.

Like many Bay Area swimmers, I had enormous respect for Cal’s legendary champion, Natalie Coughlin; I read her biography, Golden Girl, which highlighted her special working relationship with coach Teri McKeever. Both women rose to prominence on parallel tracks: Natalie earning medal after Olympic medal, Teri becoming the first woman to coach at an Olympic level. In the book, Teri is presented as a thoughtful, considerate coach, who treats Natalie like the adult that she is, by comparison to Natalie’s prior coach at the Terrapins team. Teri is also presented as sensitive to the needs of the teammates as whole young women, often counseling them on personal and interpersonal problems.

Which is why it came as quite a shock to read in the Mercury News and in the OC Register an exposé revealing serious allegations of bullying and abuse against McKeever from several swimmers:

[I]n interviews with SCNG, 19 current and former Cal swimmers, six parents, and a former member of the Golden Bears men’s team portray McKeever as a bully who for decades has allegedly verbally and emotionally abused, swore at and threatened swimmers on an almost daily basis, pressured athletes to compete or train while injured or dealing with chronic illnesses or eating disorders, even accusing some women of lying about their conditions despite being provided medical records by them.

The interviews, as well as emails, letters, university documents, recordings of conversations between McKeever and swimmers, and journal entries, reveal an environment where swimmers from Olympians, World Championships participants and All-Americans to non-scholarship athletes are consumed with avoiding McKeever’s alleged wrath. This preoccupation has led to panic attacks, anxiety, sleepless nights, depression, self-doubt, suicidal thoughts and planning, and in some cases self harm.

Following the publication of the allegations, as the Mercury News reports this morning, Berkeley swimmers walked out on McKeever on this morning’s practice.

I found myself extremely upset at learning all this; it comes in the heels of Mary Cain’s exposé of running coach Alberto Salazar’s abuse (she thoughtfully reflects on her time training with the Nike team in this great episode of the Rich Roll podcast and in this NY Times video.) We are all still collectively reeling from the sexual abuse that Simone Biles and others suffered at the hands of Larry Nassar, and from the neglect–no, dereliction of duty–on the part of their coaches and sports association to offer them any help. These latest scandals brought home the understanding that U.S. coaches and mentors were perpetrating the same horrors as the infamous Romanian and Russian coaches. Which, as someone who teaches and mentors people at these age brackets (young adults), makes me wonder – what is the meaning, or the purpose, or the appropriate concoction, of tough love?

It’s hardly disputable that the current generation of young students/trainees/athletes have a strong culture of bringing into the light things that previous generations believed should be suffered in silence. I found this interesting article about the attributes of Gen Zers as students instructive and useful. This trait, of not tolerating abuse/indignity, has both lights and shadows. At its worst, it creates a grievance mentality that encourages people to marinate in their traumas and difficulties without fostering the resilience they need (and that previous generations seemed to possess to a greater degree) to overcome them. But at its best, it makes some of us older folks question whether we should have spoken up, rather than remain silent when we suffered similar or worse harm at the hands of the people who were supposed to teach or mentor us.

As I write this, I vividly remember a whole litany of small and medium-sized cruelties that were inflicted on me during my youth and adolescence, starting with my school’s ignorance/inaction at the sadistic and systematic bullying experiences I went through between the ages of 9 and 14, continuing with the terrifying and inhospitable (albeit publicly admired and celebrated) professors and intellectuals who taught us in law school, and then with the gallery of commanders and trainers who used us, in the army, as their psychological punching bags. If anything, I marvel at the fact that the 1980s and 1990s, when all this happened to me and around me, were years in which we gradually developed sensitivity to sexual harassment, while ignoring all other forms of harassment that were still happening, unopposed, in plain sight. We regarded all that stuff as rites of passage and fodder for our hindsight comedy about the hazing we received. The thing to do, our boomer parents taught us on the rare occasion that we revealed our unhappiness to them, was to laugh it off and develop tougher skins. And I can’t say that this advice was completely misguided: later in life, when a staff member at Hastings raised her voice at me about some administrative matter or other, I calmly replied, “Girlfriend, I have been yelled at by people much scarier than you, so I propose you lower your voice and think twice about opening your mouth again.” For me, the experience of suffering was also a gateway toward empathy and compassion: I have never been incarcerated, isolated, or on death row, and I’ve never been assaulted in prison or neglected medically, but I sure as hell know what it’s like to be lonely, hated, disbelieved, and frightened, and I feel kinship with anyone who has shared this ember of the human experience, even if superficially their lives look very different to mine. At 10 years old, I wrote in my diary, “because of what is being done to me, I vow to spend a lifetime helping the helpless and the weak against the powerful bullies.” And I hope my life’s work delivers on at least some of this promise.

Perhaps my ability to grow a useful, and hopefully beautiful, lotus out of the mud comes from sheer good fortune: I just lucked into being genetically predisposed toward happiness and high energy and into having strong psychological muscles. Surely, at least some of my fellow Gen Xers may have emerged psychologically bruised from the roughness with which so many of us were handled. This makes me wonder whether the appearance that the Gen Zers we teach seem considerably more anxious, depressed, and psychologically brittle than us has more to do with their willingness to open up and report about their struggles than with their personalities. But it also has to do with the planetary anxiety (climate crisis, financial crises, political endgame horrors, soul crushing school shooting tragedies) that has characterized their formative years. Either way, the fact is that many of us teachers and mentors encounter young folks who struggle with very powerful demons–depression, anxiety, and others–and that raises serious questions about the extent to which great results can be coaxed out of people through “tough love.”

It’s important not to confuse “tough love” with an uncompromising approach to achievement, or even excellence. I staunchly believe that, by lowering standards, we are misguidedly providing a disservice to the people we try to help. I’ve seen this operate not only in my law school teaching, but also at Balboa Pool, where I work as a lifeguard. Some of my fellow lifeguards teach the Red Cross swim curriculum and are very adamant not to pass children to the next level unless they demonstrate having actually acquired the necessary skills. “They are taking my class,” said one of my colleagues, “not so that their parents will like me, but so that they will know how to swim,” which is not some fancy unimportant frivolous accomplishment: it is an essential lifesaving skill. When the big wave comes for you, you either swim or you don’t. Providing you with the feel-good illusion that can perform a task when you actually cannot is not helping you go forward in life. Similarly, giving you a diploma and a license to practice law when you are incapable of solving other people’s problems with knowledge and confidence is doing a disservice not only to you, but to your clients.

The issue I’m tackling here is quite different: it’s not so much about the standards but about the path toward achieving them. It looks like, at least in athletics (and perhaps in law schools – remember Prof. Kingsfield?) there is a dying breed of old-school coaches and instructors who strongly believe that the way to greatness–Olympic medals, world records, you name it–necessarily requires “toughening people up” through being mean to them. I find myself agnostic: surely some level of toughness and resilience is an important quality to cultivate in people who are aiming at performing and achieving at a high level. But does this really extend to a need to insult and humiliate? The public belittling and verbal punching doesn’t seem to produce the right results in this generation, but did it really prove successful in previous generations? Or did people like Natalie Coughlin, Dana Vollmer, and others accomplish incredible feats despite–rather than because–an atmosphere of toughness and abuse? Could it be that the successful folks were not the one on whose heads the cruelty was rained?

If, with the exposés of Salazar, McKeever, and others, the breed of “tough love” or just “tough” coaches is dying, we certainly have not done enough thinking on whether, and how, to get great results without the great cruelties and indignities. If it is possible, then what is the best model for this? I was very lucky to have, in grad school, the mentorship of Malcolm Feeley, who never once mistreated me, always regarded me as his protégé and friend, and always shone in my skies like a good fatherly sun. To this day I can always count on his steady guiding hand and good advice, and if I have achieved anything in my professional life, it was because, rather than despite, his infinite generosity and kindness. So I know that it can be done, and if a Malcolm-esque model of mentoring could be scaled up to athletics, the world would be better. This, of course, assumes that there’s nothing unique to sports that requires that cruelty be added to the cocktail of instructive styles and methods.

But let’s assume, for a dark teatime of the soul, that it does. Let’s assume that the medals and world records and all that are fueled, to some extent, by the cruelty. That there’s some demonstrable correlation between calling people names and publicly humiliating them and these same people running or swimming very fast and winning races. Do we really care about results so much that we are willing to accept any method for achieving them? Perhaps we’re not there yet. As my friend Aatish suggested in a conversation about this today, “the spectacle demands the next record being broken. No one is going to be all like – oh hey, it’s cool that the mile times will all get slower because now we’re being more ethical.”

And perhaps the same question applies to law school. In the above-linked piece that defends Prof. Kingsfield, Michael Vittielo writes, “Few commentators have asked whether law students are as well prepared today as they were thirty years ago, now that they graduate from far more student-friendly law schools, or whether they are less cynical if they attend law schools where their professors solicit their personal views.” If empirical evidence an be provided that law students are less well prepared now than they were in those rough Socratic method years–can it still be said, “okay, but we’re willing to sacrifice some preparation/proficiency because we don’t want to publicly humiliate our students anymore”?

A strange analogy comes to mind. During the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Speedo pioneered a techsuit called the LZR racer, which was proven statistically to have contributed to the many world records that were broken in the pool. Now, when looking at the record book, all records and results achieved by a swimmer wearing a LZR racer are marked with asterisks. If the analogy isn’t clear, let me spell it out. As more and more evidence of cruelty toward and neglect of young people in sports coaching surfaces, and as more and more of us find it abhorrent and unconscionable to treat people this way even if it produces results, will there ever come a time in which records accomplished partially as a consequence of humiliation and abuse will be marked with an asterisk for posterity, and will no longer be an accomplishment we are willing to tolerate?