My two biggest research interests–criminal justice and animal rights–come together in Karen Morin’s new book Carceral Spaces, Prisoners and Animals (New York: Routledge, 2018.) Morin, a geographer by discipline, applies insights from carceral geography to both human and nonhuman confinement contexts.

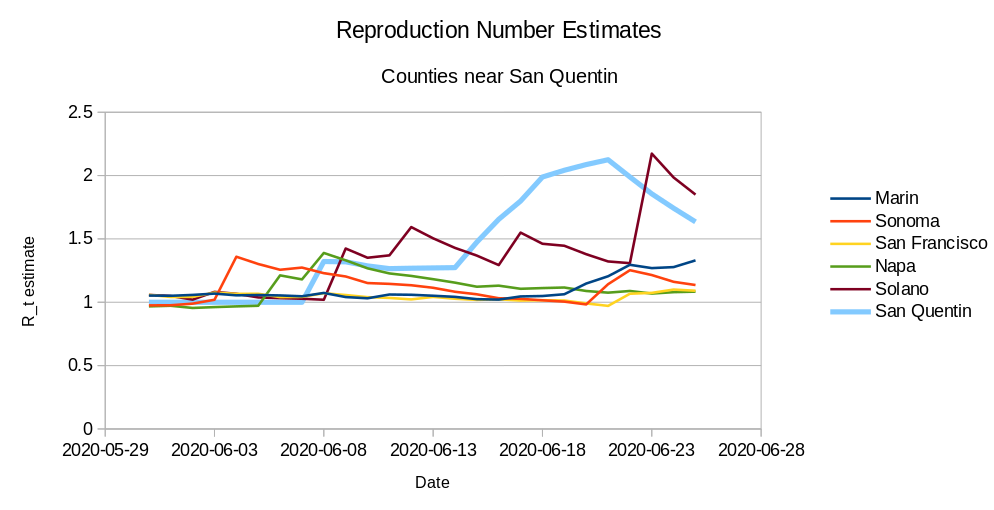

Carceral geography is a growing area of scholarship that examines prisons through a lens of spatiality. Building on work by Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben, carceral geographers problematize the overly simplistic notion of prisons as carceral spaces, arguing that prison boundaries are porous and that carceral ideologies of domination through confinement permeate spaces beyond the prison–beyond the formal dichotomy between “inside” and “outside.” Some themes studied by carceral geographers include spaces within prison and how they affect the experience of incarceration (“public” and “private” spaces within the prison; the impact of prison on the body); the interface between prisons and surrounding communities (prison towns, family members, transportation); mobility within and between prisons; and prison architecture and design. Carceral geography is directly relevant to my current research project, which is a book in progress about the COVID-19 catastrophe in California prisons; I rely a lot on the idea of prison permeability, which brings together notions of carceral boundaries, logics of opportunity (for people and for the virus,) insights from situational crime prevention, and miasma theory. In addition to this, I’m deeply interested in animal rights, and am working on a project involving the criminal prosecutions of animal rights activists who break into factory farms to release suffering animals.

In many ways, my interest in liberating nonhuman animals is an obvious extension of my interest in alleviating suffering in prisons. But the comparison is socially fraught from many directions. I often hear prison reform activists and abolitionists criticize prisons for treating people “like animals,” as if treating animals this way is fine; I’ve also heard animal rights activists criticize experimentation on animals, proposing to experiment on prisoners instead (Justin Marceau criticizes the myopic assumptions of the latter phenomenon in Beyond Cages.) I’ve also had to contend with people who find the comparison deeply offensive. Morin is well aware of these emotional and political landmines and writes:

I recognize though that the politics and ethics of making comparisons between racialized and classed human lives and that of nonhuman animals in respective carceral spaces can be problematic and fraught. It is challenging for humans who are embedded in violent, racialized, and criminalized human histories and spaces to not be offended by posthumanist comparisons to animal suffering. As noted above, the category of ‘human’ is contested in any case, and it is important to not move too quickly ‘beyond the human’ without acknowledging the continued exclusion of many human lives from full incorporation within it. And yet thinking particularly about race and animals together is important, precisely because of the way that racialized people have been and continue to be animalized in carceral spaces (Chapter 3). Moreover, the carceral logics of domination are intertwined across human and nonhuman groups. To take one more example, as Deckha (2013b) has shown, animal anti-cruelty legislation has the double effect of selecting certain animals for protection while targeting the behaviors of certain minoritized populations of people as deviant and transgressive. Meanwhile, industrial practices involving the dominant culture – as well as the abuse and killing of most animals – remain immune from critique.

Morin, Karen M.. Carceral Space, Prisoners and Animals (Routledge Human-Animal Studies Series) (p. 15). Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

This avenue is deeply productive, not only because the analogies and similarities are analytically interesting, but because solidarity across movements is essential for success. Morin’s analysis ties together the prison-, agricultural-, and medical industrial complexes, showing the intricate connections between them and the profit logics that underpin them.

Morin’s book proceeds to analyze a series of contexts in which she sees parallel developments between human and nonhuman carceral spaces. She compares execution chambers and slaughterhouses, discussing the notions of “humane” slaughter and of death sentences that are supposedly not “cruel and unusual.” She discusses the intersection of the medical and carceral spaces in the context of medical experimentation. She even asks difficult questions about prison boundaries when discussing zoos and supermax facilities. The book also makes an important contribution to two seemingly unrelated growing literatures: the one about forced labor in prisons and the one about the possibility and structure of labor rights for nonhuman animals. Throughout these topics, Morin shows deep sensitivity to the broader social structures that allow cruelty to persist.

My favorite part is Morin’s comparative analysis of prison towns and cattle towns. She shows how the introduction of an exploitative industry into a “company town” shapes the economy and the tenor of the entire town, without granting much in the way of economic benefit to the town itself (by contrast to the industry that exploits the town.) Morin doesn’t explicitly say this, but a big thing here seems the creation of a municipality that is collectively impermeable to compassion, which I think is a serious issue even when the industry is profitable.

We often talk about dehumanizing conditions in prisons. But perhaps the question is not whether or not we’re all human; the question that should matter is whether we are sentient and whether we suffer. A few years ago I read Michael Dorf and Sherry Colb’s Beating Hearts, which compares the logics of sentience underpinning the pro-life and animal rights movements and finds a way to reconcile them into a cohesive pro-choice and pro-animal perspective. I think there’s a way for advocates and activists to find peace with Morin’s comparison in a way that allows them to support both movements.

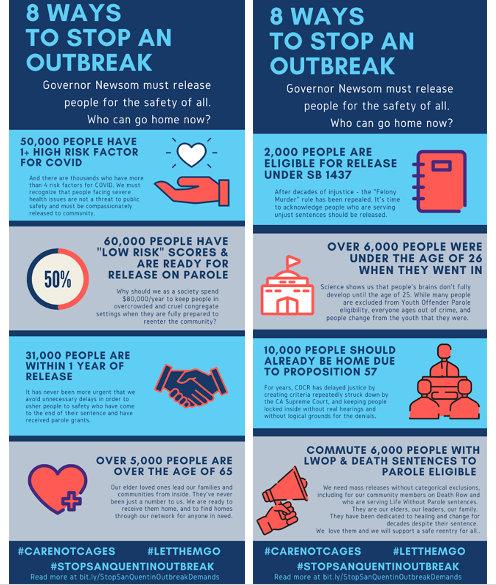

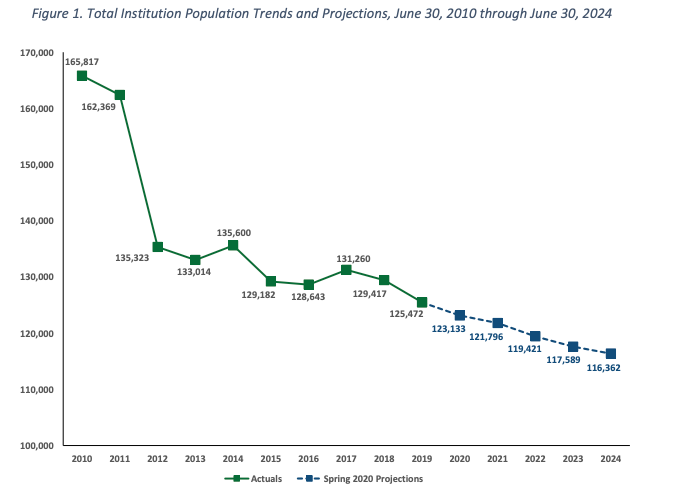

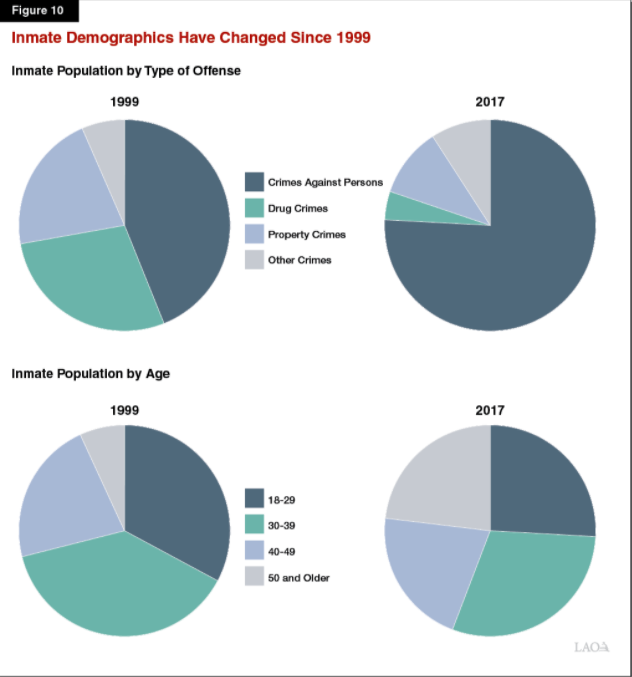

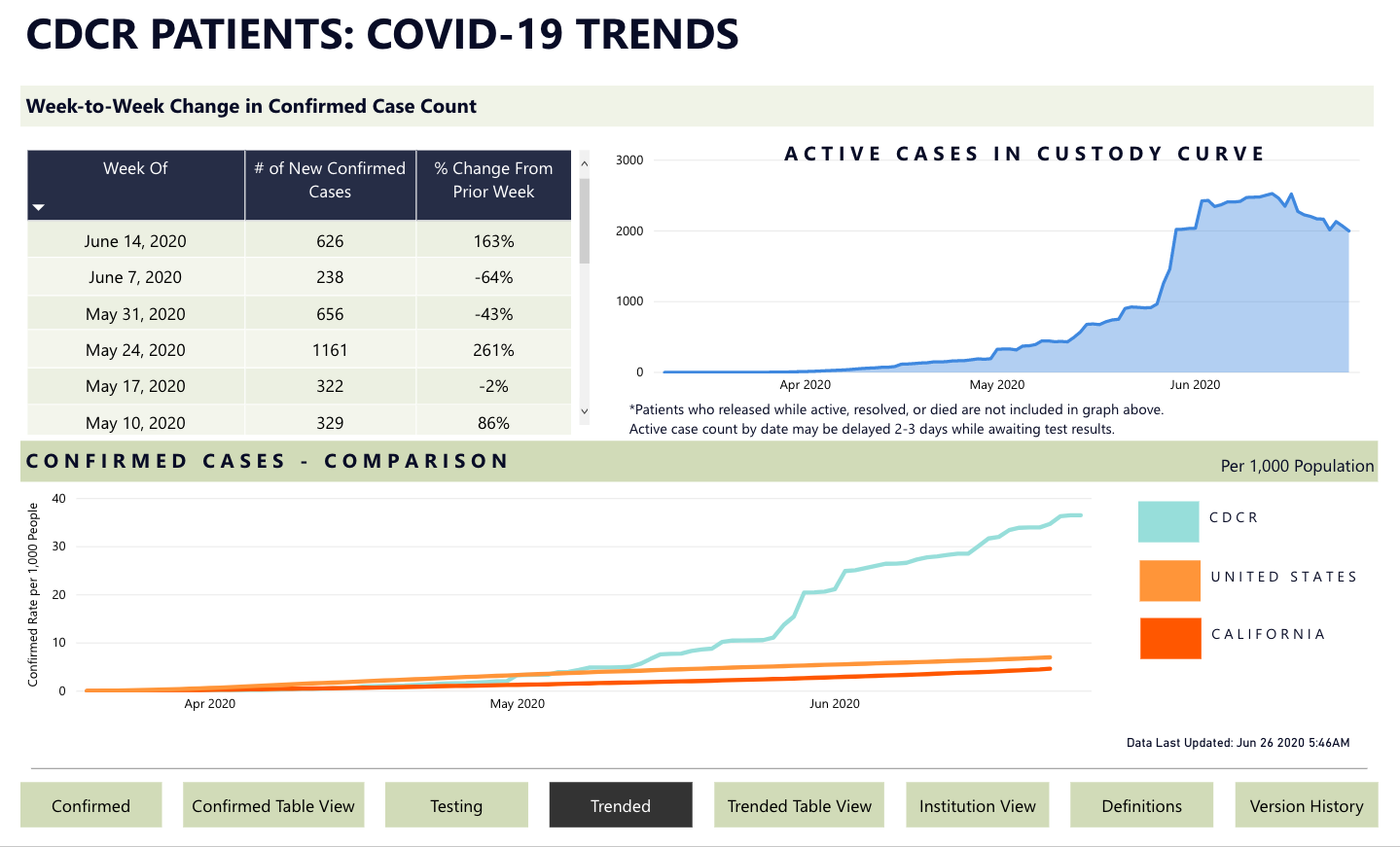

Morin admits that she has not analyzed all the scenarios that her comparison speaks to, and I found at least two that I would like to read future works on. The first has to do with the concept of overcrowding. Morin discusses issues of caging in depth, but the book does not delve into the movement toward humane farming and “cage-free” chicken facilities. Now a major selling point for eggs and for pig meats, the notion of no-cage or no-crate is deeply misleading, and some states, such as California, use various parameters to try and measure overcrowding. I’ve seen parallel developments in the context of prison population reduction orders. It’s no big secret that I think the measuring yard used in Brown v. Plata–percentage of design capacity systemwide–was deeply shortsighted, and a more careful calculation of minimal per-person area, as in other countries, would have helped us mitigate the COVID-19 catastrophe we’re experiencing right now.

The second issue I would want to read more about has to do with movement strategy, and with the reform-versus-revolution debate in the prison advocacy community. There is a parallel debate–quite a heated one–in the animal ethics community, between animal welfarism and animal liberation. Movement strategy and tactics, attention to incremental reform, and the use of the criminal justice process to challenge cruelty and obtuseness are relevant to both movements, and I think there’s more room to write about this.

These two issues notwithstanding, the book makes a fascinating read. Unfortunately, Routledge has priced it quite prohibitively, but prospective readers should know that you can rent it from Amazon for a reasonable price.