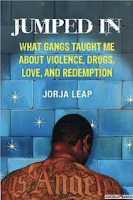

Jumped In, by UCLA gang anthropologist, educator, and activist Jorja Leap, follows her professional footsteps in researching gangs and establishing contacts with current and former gang members. Along the way, it weaves narratives from gang members’ lives with the story of Leap’s professional and personal development and struggle in conducting the research.

For many, Los Angeles gangs primarily mean bloods and crips (and the stories of those gangs are fascinating and important), but Leap walks us through neighborhoods and projects that are home to many hundreds of latino gangs, a geography that changes weekly on the streets. Making connections with gang interventionists who can provide her with introductions as well as safety, Leap interviews gang members, trying to assure them early on of her confidentiality (except in child abuse cases, which she is obliged to report.)

Her conversations with homies and homegirls reveal a wealth of details about gang life. For example, an entire chapter is devoted to gang tattoos and their significance, as well as the importance of tattoo removal for those interested in leaving gang life. Other chapters examine drug abuse, mental illness, personal histories of poverty and abuse, and the difficulties of changing one’s life around.

Among these chapters, Leap’s stories on women’s role in gang life, informed by intimate conversations with women on the ground, stand out. Her empathy for the women she interviews, and her genuine attempt to understand and help, are particularly touching, and she does a great job exposing domestic violence, which she considers the one unaddressed problem in gang intervention. Her narrative is nuanced enough to accommodate battering that victimizes men (a phenomenon often underreported and misunderstood). She handles the parallels to the abusive aspects of her own first marriage with subtlety and grace, understanding the class difference and respecting the common and unique features of the experience.

Another theme in the book is the strength of gang connections and the pull of street life. Here, the narrative is somewhat less successful. Leap rejects the oversimplification of the popular notion that “you can never leave the gang”, but her own interviews and examples confirm the immense difficulty of doing so, as people derive so much of their identity and community from the gang. Her upset at juries and district attorneys disbelieving change is therefore left empty, and the reasons behind it (beyond belief in this or that person’s innocence) unpacked.

Leap also speaks to the complex relationship between gangs and drugs, rejecting the notion that drugs are sold in corporate-like hierarchies, and instead revealing a less structured drug trade stemming out of poverty and lack of opportunity.

The book is on shakier ground where policy prescriptions are concerned, and when thrown together at the end of the book, they read a bit disjointed. Leap’s overall preference for long-term holistic solutions over emergency interventionism, of which she is ambivalent. The book oozes contempt for David Kennedy’s slick marketing of his “ceasefire” plan (“give me 50 million dollars and I’ll solve the gang problem”), but not a lot of actual arguments against it. In fact, Leap has respect for some forms of interventionism as heroic and important in acute situations. Where the book takes an unequivocal stance is in its justified support for the incredible work of Homeboy Industries and the relentless work of Father Greg Boyle.

This is not an academic book, and as such it offers a dimension seldom explored in academic texts – the experience of the researcher herself. Leap weaves her gang research journey with her personal life, including her candid examination of her second marriage to a widowed LAPD officer and adoption of his daughter. The account of the marriage unflinchingly explores the frictions between Leap and her husband over professional approaches to gang violence and danger on the job. Far from another self-serving “women can’t have it all” essay, this is an expose of a professional woman’s struggle to be respected, not only on the streets but at home, for what she does. There is also hope offered, for after Leap’s husband’s retirement from the LAPD, his approach becomes more flexible and he finds himself joining the efforts to rehabilitate gang members. Another way in which this personal approach might speak to researcher is its gentle exploration of the thin line between researcher and activist. Leap’s description of her subjects is refreshingly empathetic; she is deeply involved in their lives and spends her time not only evaluating projects, but writing grants and actually teaching life skills. At times, the contrast between her values and those of her subjects is jarring, but she handles it with grace and tact, honestly exposing her internal conflict for the readers.

All in all, Jumped In is an engaging read that makes you care about Leap’s friends and acquaintances on the street and confront our ignorance about gangs, but for rigorous, in-depth understanding of gangs we should read her academic publications.