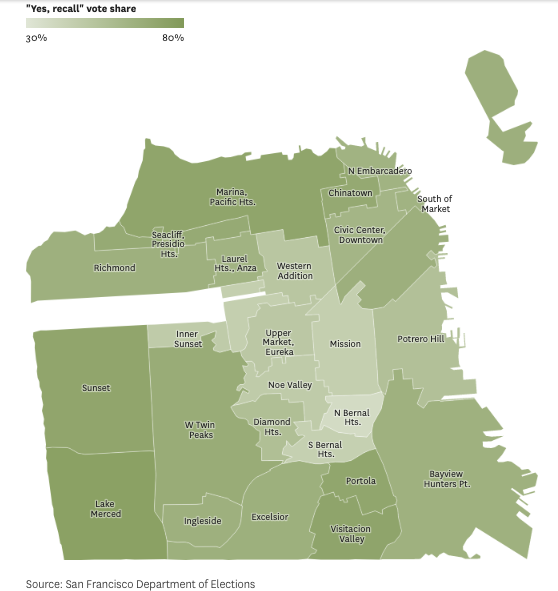

One of the defining features of the last election was the passage of a slew of propositions diverting funds away from the police department. Inspired by the vocabulary of movements (defund! abolish! dismantle!) but not always referencing this vocabulary explicitly, these propositions aimed at shifting the approach toward addressing social problems toward social services, mental health, and harm reduction approaches to narcotics.

But it turns out that things are more complicated than expected. The Chronicle’s Bob Egelko reports today:

As homicides rise throughout the Bay Area during the coronavirus outbreak, San Francisco police have reported 45 killings this year, compared with 41 for all of 2019. Black people, who make up less than 6% of the city’s population, accounted for nearly half the victims.

The 41 slayings reported in 2019 were San Francisco’s lowest total in 56 years. Police reported four homicides in January and February this year, but the numbers began to rise as the pandemic set in, even as most other crimes were declining. As residents grow more fearful, gun sales are also increasing and have reached record levels nationwide.

Homicides in the Bay Area’s 15 largest cities increased by 14% in the first six months of 2020 compared with 2019, The Chronicle has reported. In Oakland, with a population of 435,000 compared with San Francisco’s 896,000, killings totaled 79 as of mid-October, a 36% increase over 2019.

The homicide totals do not include any fatal shootings by police.

In San Francisco, police said, the victims of the year’s first 43 homicides included 20 Blacks, seven Latinos or Latinas, seven Asian Americans and six non-Hispanic whites, with the rest from other groups. The two most recent killings, a double homicide Nov. 18, are still under investigation, police said.

Indeed, the trend is the same in Oakland, and the political implications are too important to ignore. Earlier this month, Rachel Swan reported:

Heeding the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement, Oakland leaders committed over the summer to ultimately slash the Police Department’s budget in half, by about $150 million. The City Council created the 17-member Reimagining Public Safety Task Force to figure out how to meet this lofty goal to “defund the police.” They would write a draft proposal by December and present it to the council in March.

Then a wave of gun violence engulfed the flatlands in East Oakland, home to the city’s most impoverished neighborhoods. Homicides spiked. Policymakers — and even the most devoted reformers — had to confront a paradox: that the Black and Latino neighborhoods most threatened by police violence are also the ones demanding better and more consistent law enforcement.

Task force members agreed that police brutality against Black and brown people is too common, that gun violence needs to end and that the city needs more services to address the underlying causes of crime. But while advocates wanted swift, dramatic change, others felt conflicted. In neighborhoods with high crime and slow police response times, Black residents winced at what sometimes felt like preaching from outsiders.

A poll released last week by the Chamber of Commerce showed that, citywide, 58% of residents want to either maintain or increase the size of the police force. That figure climbs to 75% in District 7, an area of East Oakland where gunfire exploded this summer.

The reason I get a rash every time I hear the defund/abolish/dismantle refrain is that, years ago, I realized the fundamental problem with American policing: it’s not about too much or too little policing, it’s about the wrong kind of policing. I got there in three parts. First, I read Alexandra Natapoff’s fantastic article Underenforcement, which theorized the problem of too little policing and why it affects especially the neighborhoods where people assume there’s too much policing going on. Then, I read an interview with the wonderful David Simon, who spent the earlier part of his career as a crime reporter following the Baltimore homicide detectives (and writing this marvelous book.) He explained why the reward system for police officers incentivized stop-and-frisk policing and disincentivized crime solving:

How do you reward cops? Two ways: promotion and cash. That’s what rewards a cop. If you want to pay overtime pay for having police fill the jails with loitering arrests or simple drug possession or failure to yield, if you want to spend your municipal treasure rewarding that, well the cop who’s going to court 7 or 8 days a month — and court is always overtime pay — you’re going to damn near double your salary every month. On the other hand, the guy who actually goes to his post and investigates who’s burglarizing the homes, at the end of the month maybe he’s made one arrest. It may be the right arrest and one that makes his post safer, but he’s going to court one day and he’s out in two hours. So you fail to reward the cop who actually does police work. But worse, it’s time to make new sergeants or lieutenants, and so you look at the computer and say: Who’s doing the most work? And they say, man, this guy had 80 arrests last month, and this other guy’s only got one. Who do you think gets made sergeant? And then who trains the next generation of cops in how not to do police work?

Then, I read Jill Loevy’s heartbreaking Ghettoside. Loevy shows how the LAPD homicide detectives are unable to solve murders because witnesses won’t cooperate with them. What she says at the outset of the book (pp. 8-9) is so powerful, and so easy to obfuscate, that it calls for a long quote.

This is a book about a very simple idea: where the criminal justice system fails to respond vigorously to violent injury and death, homicide becomes endemic.

African Americans have suffered from just such a lack of effective criminal justice, and this, more than anything, is the reason for the nation’s long-standing plague of black homicides. Specifically, black America has not benefited from what Max Weber called a state monopoly on violence the government’s exclusive right to exercise legitimate force. A monopoly provides citizens with legal autonomy, the liberating knowledge that the government will pursue anyone who violates their personal safety. But slavery, Jim Crow, and conditions across much of black America for generations after worked against the formation of such a monopoly where blacks were concerned. Since personal violence inevitably flares where the state’s monopoly is absent, this situation results in the deaths of thousands of Americans each year.

The failure of the law to stand up for black people when they are hurt or killed by others has been masked by a whole universe of ruthless, relatively cheap and easy “preventive” strategies. Our fragmented and underfunded police forces have historically preoccupied themselves with control, prevention, and nuisance abatement rather than responding to victims of violence. This left ample room for vigilantism—especially in the South, to which most black Americans trace their origins. Hortense Powdermaker was among a handful of Jim Crow–era anthropologists who noted that the Southern legal system of the 1930s hammered black men for such petty crimes as stealing and vagrancy, yet was often lenient toward those who murdered other blacks. In Jim Crow Mississippi, killers of black people were convicted at a rate that was only a little lower than the rate that prevailed half a century later in L.A.—30 percent then versus about 36 percent in Los Angeles County in the early 1990s. “The mildness of the courts where offenses of Negroes against Negroes are concerned,” Powdermaker concluded, “is only part of the whole situation which places the Negro outside the law.” Generations later, far from the cotton fields where she made her observations, black people in poor sections of Los Angeles still endured a share of that old misery.

This is not an easy argument to make in these times. Many critics today complain that the criminal justice system is heavy-handed and unfair to minorities. We hear a great deal about capital punishment, excessively punitive drug laws, supposed misuse of eyewitness evidence, troublingly high levels of black male incarceration, and so forth. So to assert that black Americans suffer from too little application of the law, not too much, seems at odds with common perception. But the perceived harshness of American criminal justice and its fundamental weakness are in reality two sides of a coin, the former a kind of poor compensation for the latter. Like the schoolyard bully, our criminal justice system harasses people on small pretexts but is exposed as a coward before murder. It hauls masses of black men through its machinery but fails to protect them from bodily injury and death. It is at once oppressive and inadequate.

The crux of the matter is something that has been tragically true for decades, but “my side” of the criminal justice debate is always too reticent to mention: African American people–the people whom “defund” initiatives are purporting to protect–are vastly overrepresented as both homicide perpetrators and victims. Time after time I see mental and linguistic gymnastics in academic and journalistic circles pretzeling around this simple, true statistic (note the quotes above from solid, responsible journalists, focusing only on victimization.) I know there are good intentions behind this–the fear to stereotype–and I also know there are performative reasons: in the era of Kendi and DiAngelo reeducation camps in our campuses, no one wants to appear racist. We are repeatedly admonished that asking the right question (“what about black-on-black crime?”) is in itself racist, so how are we ever going to get any answers? The thing is, there is an obvious explanation for this, and it’s not racist at all: When one lives in poverty and is consistently treated as a second class citizen, and when legitimate opportunities to thrive are not available, a larger proportion of the population will recur to illegitimate ones.

This is so obvious that everyone I speak to behind bars, when reflecting about their own lives and how they ended up in prison, say the same thing: recurring to violence as part of the drug trade is situational and comes from a very diminished repertoire of opportunities and choice. As James Forman explains here, is much easier for “my side” of the debate to focus on drug offenses, where we know that white and black people use and sell at about the same rates, and explain the disparities by overactive stop-and-frisk policing. But what do we do about explaining disparities in violence? Overpoliced poor neighborhoods do not explain disparities in bodies on the ground. It was therefore eye opening to read Scott Jacques and Richard Wright’s Code of the Suburb. In a shorter article, Jacques and Wright explain why it is that suburban, middle-class, white drug dealers don’t get mixed up in homicides: not only were they raised in the conflict-avoiding “code of the suburb”, but they knew that they had bright futures ahead of them and the stakes were too high:

Compared to their urban counterparts, it was easier for the suburban dealers to give up dealing because they didn’t really need the money. Their parents were able to provide for them, so for these teens, dealing was never meant to be a career. It was just another phase on their way to becoming successful adults, which they had no intention of jeopardizing.

In the 1950s, studying juvenile crime was all the rage among criminologists. One promising avenue was the opportunity theory developed by Cloward and Ohlin. They argued that the kind of crime one recurs to–not only whether or not one starts engaging in criminal activity–depends on what kind of opportunities are available in one’s neighborhood in terms of resources, know-how, role models, etc. Some of my colleagues have made a name for themselves trashing Cloward and Ohlin and retroactively branding their theories as racist (again, following the principle that any focus on crime committed by people of color that does not explain it away as discriminatory policing is racist.) The effort to take what was a solid step forward and rebrand it as reactionary and outside the realm of the sayable reminds me of Mark Twain’s saying, “the radical of one century is the conservative of the next. The radical invents the views. When he has worn them out, the conservative adopts them.” But if you read Jacques and Wright, you have to conclude that, in basics, what Cloward and Ohlin said was so spot-on that it still stands: the same systemic racism that produces discriminatory policing also produces differences in violent crime perpetration rates. And the tragedy is that, no matter how you look at it, it’s poor people of color who lose. They are hounded and humiliated by paint-by-numbers policing that doesn’t solve crimes, they are themselves victimized by violent crime at higher rates, and because their uphill battles are not solved from the root in this uncaring, hypercapitalist society, they also recur to crime at higher rates. All these things come from the same roots, but somehow saying the first two is fine, while saying the third out loud runs the risk that your colleagues will treat you as if you have cooties.

I think we’re seeing a refreshing change, though, and more folks–like Simon, Loevy, Forman, Pfaff, Jacques and Wright, and Natapoff are willing to point out that the problems caused by poverty and deprivation cannot be brushed away just because it’s inconvenient to discuss them. Recently, they have been joined by David Garland, whom no one can suspect of being some sort of right-wing reactionary nut. Lisa Kerr summarized the main points in the following tweet thread:

As always, fascinating keynote from David Garland at @CCR_UofA Prisons and Punishment conference this morning. He started by making clear that we should not avoid fact of racial difference in homicide / violent crime rates in the US (in both commission and victimization).

Conservatives repeat and liberals avoid this data – but that’s a mistake. These real differences have nothing to do with intrinsic characteristics. Must ask: how does this fact pattern emerge? Segregation, economic exclusion, absence of social services, deep poverty.

Garland is also clear that policing operates in a more dangerous environment in the US than in other countries, due to guns. Police at work are killed at a higher rate, as are civilians by police.

Central claim was that the relaxation of Democratic commitment to economic politics, after New Deal, in favour of identity politics, has had bad effects. Plus: we should spend more time calling for economic justice, less time calling for defunding police / abolishing prisons.

Garland says that “Defund Police” is “a slogan that can’t mean what it says.” No modern nation has abolished police, would mean (1) private security for rich (2) poor communities exposed and vulnerable.

We should be saying “Defund the Rich.” Tax more to fund police, fund social services and safety net, and transform the police: abolish militarization and improve accountability mechanisms.

Notably, someone asked, can’t we do ‘all of the above’? Garland is firm that “Defund Police” is very ill-conceived and has benefited Republicans, even as Democrats worked hard to distance themselves from it.

These tweets don’t do the talk justice. Be sure to watch. (I was transported back to graduate school when I had the ridiculous good fortune to learn from Garland for several years. I have craved his perspective even more in these difficult months.)

Watch the whole thing:

What we need is not more policing or less policing. We certainly don’t need slogans. What we need is to rethink the very nature of policing and rebuild policing from the ground up. How we promote and reward police officers must change to disincentivize stop-and-frisk abuses and incentivize crime solving–for everyone’s sake.