In my previous writings about the COVID-19 prison disaster (especially here and here), I relied on Ben Bernanke’s famous “triggers and vulnerabilities” model. I explained that the virus happened on a fertile Petri dish of neglect, both preceding and following the Plata litigation. But it’s just occurred to me that there’s a better way of explaining why the problem lies not only with the prison healthcare crisis that preceded Plata, but also with the Plata remedy itself: Criminal justice reforms in CA (through litigation as well as legislation) are often like homeopathic remedies: a low-concentration of the exact problem they purport to solve. The crisis we are facing now is merely an exaggerated example of the futility of homeopathic criminal justice reform.

Homeopathy, the creation of Eighteenth-century physician Samuel Hahnemann, follows an idea known as the Law of Similars – the idea that, if exposure to substance X causes symptom Y in a healthy person, substance X can cure symptom Y in a person where they occur naturally as part of a disease process. For example, exposure to onions causes an itchy, stinging sensation in the eyes; therefore, the homeopathic remedy for hay fevers or head colds accompanied by such sensation is a low-concentration formula of onion.

I’ve come to see criminal justice reform initiatives in California as low-concentration forms of the underlying problems they purport to solve. The COVID-19 “relief” policies sold to us by the Governor and CDCR are a case in point.

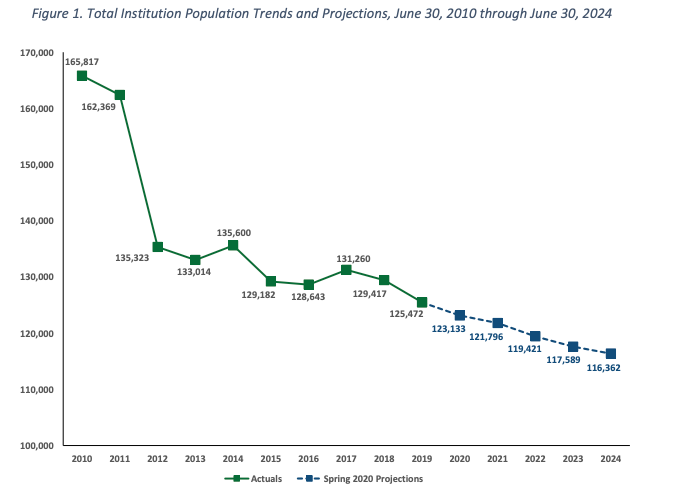

The problem we had to solve was a giant, bureaucratic correctional monster, which we could not wrangle. The Plata solution: we made it more complicated by breaking it into 59 monsters that have an equally unwieldy, though different, structure. We’re now dealing with the ramifications of this homeopathic preparation: inscrutable BSCC reports on jails alongside journalistic exposés of serious outbreaks; four months of delay before numbers were even available; traffic between jails and prisons that is unpredictable and difficult to regulate.

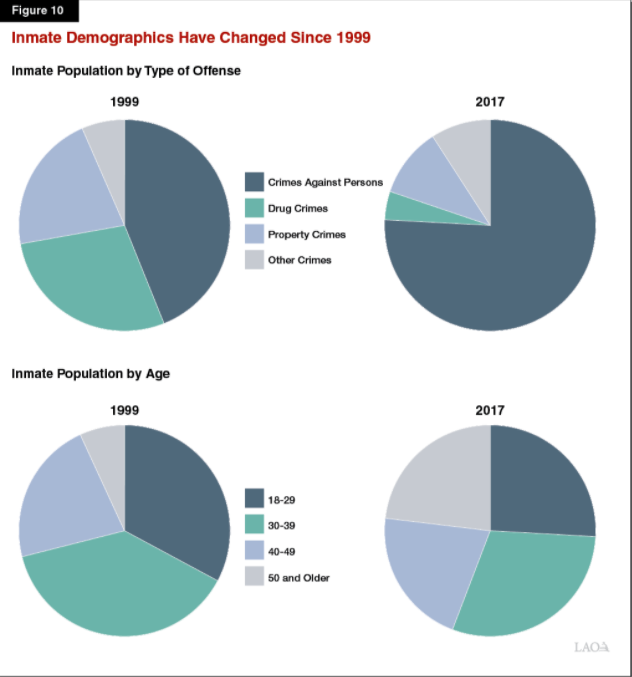

The problem we had to solve was the rate (and percentage of the general prison population) of aging, infirm people serving interminable sentences. The Plata solution, the Prop 47 solution, the Prop 57 solution: reinforce the notion that these people belong in prison by designing all releases around the issue of nonviolent offenders. While removing people from prison (diluting them) this, ironically, increases the concentration of aging and infirm people in prison so that they are the ones exposed to healthcare scandals.

The problem we had to solve was a bloated correctional apparatus, whose provenance was decades-long oversensitivity to victim pressure groups advancing a monolithic vision for alleviating their plight: Monstrous sentencing policies. The solution we’ve devised for COVID-19? Anticipate the sensitivity and address it by avoiding releases of people convicted of violent crime.

The problem we had to solve was a “correctional free lunch”, in which people in the community were largely unaware of the costs of our correctional system because these were concentrated in large facilities in rural and remote areas. The solution? Now we encourage community-prison alienation through jurisdictional jockeying for position between county health officers and the prisons that are literally located amidst these counties and irrational fears that releasing people will infect the community (the opposite is true: incubating the disease in prisons is much more risky for communities.)

As we’ve seen in the COVID-19 release plan (before and after its implementation), and just like homeopathic formulas, diluting the problem results in obtaining a placebo at best, and a worsening of the problem at worst. The logic of the Law of Similars is supposedly an appeal to the idea of a “natural law” principle, but actual science refutes this: what makes sense is to treat an ailment with an antidote, not with a diluted version of the same ailment. The antidotes are obvious to me: Thin out the monster by locking fewer people up in fewer places. Do not lock up aging, sick people. Give victims/survivors better roles than the world curators of what should happen to offenders.

Which brings me to why I think the analogy matters. As I’ve explained elsewhere, I don’t think this is some evil, sadistic ploy at work here. I think what’s stopping state and prison officials from applying the antidotes is institutional intransigence and fear. Homeopathy itself was borne of Hahnemann’s disgust with the medicine practiced during his era: bloodletting, leeching, purging, etc. By contrast to these harmful measures, the delicacy of the diluted solutions was mellow and reassuring. Here, too, there’s immense fear of what would happen if drastic measures were taken. I saw this logic at the recent federal Plata hearing (though, admittedly, the PLRA plays an important role here, too) and also at the two state courts. We don’t like drastic solutions and purging; better to drink a Bach Flower distillation.

Ashley Rubin’s forthcoming book The Deviant Prison looks at why the Pennsylvania incarceration model, practiced at Eastern State Penitentiary, persisted long after it was proven not to work. I see the same form of institutional obstinance at work here. And, by contrast to Eastern State, this is perpetuated because homeopathic criminal justice reform has become the habitual, accepted mode of doing things. It might be sobering to realize that homeopathic preparations are the only category of alternative medicine products legally marketable as drugs. Quackwatch explains that this situation is the result of two circumstances. First, the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which was shepherded through Congress by a homeopathic physician who was a senator, recognizes as drugs all substances included in the Homeopathic Pharmacopeia of the United States. Second, the FDA has not held homeopathic products to the same standards as other drugs. Today they are marketed in health-food stores, in pharmacies, in practitioner offices, by multilevel distributors, through the mail, and on the Internet. I think that our habituation to homeopathic criminal justice reform has created a similar situation, where we are willing to accept these placebo solutions because the ideas that drive both the problems and the solutions have been so hammered in, that we can’t imagine anything else.