In 1992 I left home and moved to Jerusalem for law school. Being on my own for the first time was an opportunity to revise and question many habits, including my nutrition. The impetus for becoming vegetarian came from a humiliating (but, in hindsight, funny) incident: in my first year of law school I dated a classmate who came from Jerusalem’s academic aristocracy. His family invited me to a famous gourmet steakhouse. I had obviously not grown up eating such fancy things and had no idea how to order my steak, so I thought well-done would be safe, and they proceeded to repeatedly ask me throughout the meal in concerned tones: “Are you sure your steak is not too dry?” That meal was the last nail in my carnivorous coffin; I eschewed animal flesh that evening when I came home.

Ours was not a kitchen-centered household, and my hard-working mom would bring me food from restaurants near the courts where she tried criminal cases as a defense attorney; so, being a serious person, I decided to teach myself how to cook and eat vegetarian by purchasing my first cookbook, Phyllis Glazer’s A Vegetarian Feast. I also discovered an amazing natural foods grocery store in a nearby kibbutz, Ramat Rachel, which was a complete revelation. It was there that I encountered whole grains for the first time, as well as exotic things like tofu (promoted as “soy cheese”); I come from fairly humble beginnings and did not grow up eating such foods. My new way of life was strange to my family, who were pained by my avoidance of meat and were puzzled by the whole grain thing (gradually, they all came around.)

My knowledge of nutrition was fairly limited at the time; the reigning theories of vegan and vegetarian nutrition were the now-debunked “food combining” and “complete protein” myths, which seemed like a whole lot of trouble. I had no concept of the extent to which the cruelty to animals permeated the dairy and egg market (I did buy “cage-free” eggs after visiting an army colleague’s home and being horrified by her family’s chicken coops.) And I had no idea how to stay healthy on a vegan diet; vegetarianism was already a pretty radical step considering where I came from. So, I was a lacto-ovo vegetarian, and remained such until getting to the States in 2001.

Arriving in America was a harsh blow to my health and digestive system. U.S. food was richer, more laden in chemicals, and far less fresh and healthy than its Israeli counterpart, and throughout grad school I suffered from debilitating stomach aches and miseries that would put me out of commission for days at a time. With the help of a wonderful nutritionist I met through my Chinese medicine studies at the Acupressure Institute, I did an elimination diet and eschewed bread and dairy; I immediately felt better. Since I didn’t quite know what to substitute it with, I went back to eating fish. Meat crept back into the menu several years later, when I was training for long marathon swims. I thought I needed the protein, but the whole thing never sat well with me, morally and ethically.

Everything changed in 2014, when I saw Judy Irving’s wonderful documentary Pelican Dreams and suddenly realized that everything was interconnected–the food chain, the ecosystem, the planet, our health, the health and welfare of our nonhuman friends–and that I wanted nothing to do with the animal torture industry. I came home that very evening and told my partner I was going to be vegan from now on (he joined me not long after and we’ve been happy and proud vegans ever since, raising a happy and proud vegan son.) I became involved with Direct Action Everywhere and started writing about factory farms and open rescue. It was also, as it turned out, an easy and convenient time to go vegan, because the next generation in quality nut cheeses and meat substitutes emerged.

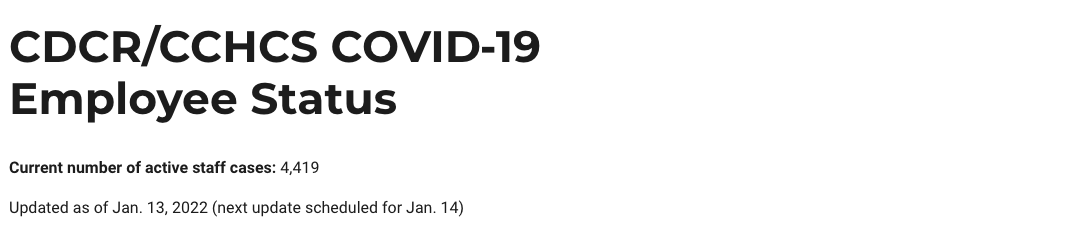

During the pandemic, we relied a lot on these substitutes, which were not only easy to procure and order in, but also psychologically soothing (salt and oil will do that.) My weight started creeping up to an alarming degree, and unpleasant, debilitating symptoms, which I had ascribed to perimenopause, became a way of life: relentless low-grade headaches, digestive problems, brain fog. Litigating the San Quentin case and advocating for incarcerated people during the pandemic took an enormous psychological toll, and my health continued to deteriorate. In March 2021 I fell in the street and could not get up – to this day I’m not sure if it was cardiac or something else. It was a sense of utter weakness and frailty. But at that instant, all the shame I had been feeling about my health decline turned into rage: I don’t deserve to live like this, I thought, I deserve a better life. The next day I bought all the vegetables and fruit I could think of and took a walk around the block. I juiced for 30 days, then added fresh salads, soups, and smoothies to the menu. The walks grew in length and became runs, I bought a bike, I started swimming again, I completed my lifeguard training. In March 2022, a year after I fell in the street, I completed the Oakland Marathon. At that point, all my symptoms were gone, my bloodwork cleared up, all my health metrics were transformed, and I lost 60 lbs, getting back to my high school weight. My swim and run times were, and are, better than ever in my life, and I continue seeing personal bests in the pool and on the trail.

Most of the inspiring success stories on the Forks Over Knives website involve folks who ate the standard American diet before shifting to a whole-food, plant-based plan. I’m here to tell you that it’s entirely possible to be 100% vegan and eat in a horribly unhealthy manner. I’m so glad I shifted to whole foods, juices, smoothies, chilled soups, and other vegetable-rich meals. I am sure that eating this way has saved my life. On social media, I frequent various vegan groups, and many of the posts involve a search for the perfect meat analog, faux egg, or rich cheese on a pizza; I very keenly recognize the feelings driving this quest in myself as well. It’s not just cravings from the animal-consuming days; it’s a sense of deprivation and righteousness. Whenever I crave something like this, I detect in my own thinking a sense that dammit, I’m doing the right thing here for the animals and the planet, I deserve this tasty reward.

I have found a way to set aside this righteous thinking pattern: I interrupt it by thinking, what I deserve is to feel splendid, wake up fresh and pain-free, and live many years to be with my son and to push myself to athletic heights. That’s my reward. The way to earn my “just desert” is through chilled green soups, delicious salads, and concoctions rich in healing greens. To learn more about nutrition, I’ve read up on the latest research on a variety of conditions, and taken my plant-based nutrition certificate from the T. Colin Campbell Center for Nutrition Studies, as well as the Forks Over Knives cooking course. I feel so wonderful now that I don’t want to ever not feel this way; I wake up every morning yearning for everyone to feel this way. It’s hard to describe how profoundly pleasing it is to go about my day with everything humming and working the way it should. I want the same for you, and for everyone else.