Like many people of good conscience, I was angry and upset to hear the news last night. The acquittal of George Zimmerman, while not wholly unexpected given the trial coverage, has been a punch in the stomach for those of us who saw race relations in America dramatized yet again in this incident. It is also hard to see this as an isolated incident, and those of us who experienced frustration and rage at the verdict of Johannes Mehserle, who shot Oscar Grant in front of dozens of onlookers are even more enraged and hopeless today.

Which is why this post is a hard one for me to write. Because I have hard things to say, and they will not heal our broken hearts or silence our voices from crying out in indignation today. But maybe they are still worth saying.

Legal Truth and Factual Truth

We all know this, but it bears repeating: Criminal law doctrine–stripped of all realities and considerations and constraints and group effects–allows convicting people only if the evidence supports their guilt beyond reasonable doubt. What that means, exactly; whether it allows for majority decisions; whether jurors understand how to quantify it; and how it relates to actual innocence is a different question. But finding someone not-guilty at trial is not a factual statement that the person did not commit the crime. Also, which is less obvious, finding someone guilty at trial is not a factual statement that the person committed the crime. The legal system would have us believe that it takes legal guilt seriously. That is, that it hopes that legal guilt will approximate, as much as possible, factual guilt. And much of the premise behind the post-Warren court’s chipping away at the Bill of Rights was exactly that: No one wanted factually innocent people to go to prison, but we weren’t all that excited about the factually guilty going free. The legal system and the rule of law rely on legitimacy from the public, and to garner that legitimacy the façade of truth in convictions has to be maintained.

But deep down, the system knows it makes mistakes. Dan Simon’s In Doubt, which analyzes the causes of wrongful convictions, cites the astonishing statistic that we may be wrongfully convicting up to 5% of all people found guilty at trial. We acknowledge this to the point that habeas proceedings have an “actual innocence” exception to the cause and prejudice rule. Part of the reason for this may be that Doreen McBarnet is right, and that the system is inherently biased toward conviction. Throw in one more important factor: Six jurors is a lot less than twelve, which makes not only for cheaper trials but also for an increased tendency to come to a guilty verdict in weak cases. So, six people came to an unpopular decision, and we may disagree with them. But I certainly do not envy them. I have, perhaps, an inkling about the political culture these folks will be going back to this morning, but I still think it’s going to take a lot of guts to explain this legal decision to people who don’t believe the factual assertions behind it.

Facts and Symbolism

Do you know what happened in that Florida gated community the morning that George Zimmerman killed Trayvon Martin? And by “know”, I mean, are you absolutely certain of what happened? And can we be certain at all? I wasn’t there, and neither were you. And even if we were there, or saw a video, we could not be sure.

But you and I have a fairly good idea in our heads, and that idea differs from what six Florida residents decided yesterday. We listened to the tape, and we know that Martin was not armed, and we think that Zimmerman, who was motivated by hypervigilance and racial animosity, shot a defenseless man. And my fear this morning has been that we are allowing the symbolic value of this incident, as we did when Oscar Grant was shot, to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of what happened.

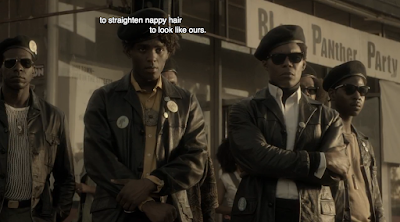

The much-awaited movie Fruitvale Station (trailer above) opened yesterday in Oakland theaters. I didn’t see it, but am planning to do so soon; yesterday I had a chance to talk to some people who saw it, and one of them told me that a relative who came with him wanted to know, at the end of the film, whether it was “romanticized.” Films are never an accurate description of the truth, because the truth is messy and does not make for a neat and coherent story. But the story in the film resonates very strongly with those of us who were in Oakland the night of the protests, because it epitomizes what we know and believe is true, namely, that racism is alive and well in America. This feeling would be valid whether or not Mehserle reached to the taser or Zimmerman was attacked by Martin. Because it goes to the heart of a problem, and not to the details.

I read some reviews of Fruitvale Station, which were for the most part laudatory. One of the few exceptions was this piece of drivel by the NY Post’s Kyle Smith. You don’t really need to see the movie to learn something from this review–namely, that Smith doesn’t see Oscar Grant as a human being worthy of life and dignity. To him, Grant is merely a “criminal” and a “recent San Quentin resident,” the “only remarkable aspect” of whose life “was its end.” I suppose that for Smith, as for many people (and, judging from his words to the 911 operator, for George Zimmerman), human life doesn’t have intrinsic value when the person living it has darker skin and a criminal record. I don’t think any of us needs to canonize Grant or even Martin to understand this terrible truth (even though an unarmed honor student is, perhaps, easier to canonize.) That their lives and deaths are a morality tale about the fragile concept of sanctity of life in America for black and brown men is important enough. They don’t have to be all good and flawless. No one is. Even the people we have canonized, like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., were real human beings with flaws and weaknesses. And when we wear the hoodie, we are not, perhaps, making a factual statement about an interaction we didn’t witness, but about its symbolic meaning.

A Racialized Criminal Justice System

Perhaps the resentment about Zimmerman’s verdict comes not from this place of truth and symbolism, then, but from a bitter acknowledgment that a black defendant would not have received this careful consideration, determined defense work and benefit of the doubt. It is one more data point on our chart of racial inequities in the system. When we decry the correctional binge that has bloated America’s prisons for the last four decades, we highlight the obvious racial aspect of it. Some of us go to the extent of referring to the incarceration system as the new Jim Crow.

As James Forman reminds us, however, the picture is more nuanced. A growing number of white people are criminalized, incarcerated, and their lives savaged by the meth plague, much as the not-imaginary crack epidemic savaged African American communities in the 1990s. Black and brown young men are incarcerated at much higher rates, but the white population is rising steadily as well and possibly faster. Contrary to what we believe, the prison inflation is not solely or even predominantly due to nonviolent drug crimes; violent crimes play a big role, and African Americans perpetrate more of those crimes, which are less open to interpretation. All of this does not mean that the criminal justice system is not racialized or that racism does not exist. Of course it does. But the roots of racialization may be much deeper than merely incarceration rates or stop-and-frisk practices, and go back in history to a place of coercion, slavery, torture, and the resulting deep-reaching inequities. Convicting a white man who killed a black man, no matter how enraged his particular story makes us feel, would not do anything to fix this. It would merely add one more inmate to the population.

The Empty Promise of Punitivism

Why would convicting Zimmerman not make us feel better this morning? Some of us, especially Trayvon Martin’s family, would perhaps find some comfort in a conviction. Even this is not a certainty. Tragically, a conviction will not bring Trayvon back to them, or to any of us, and the anguish and despair experienced at the loss of a loved one is a personal experience that takes its own course toward healing.

And what about the rest of us? Would a conviction make for a better tomorrow? Let’s, indeed, imagine an alternative universe, in which a guilty verdict sends Zimmerman to prison. The racialized lines formed around the trial will accompany him to prison and intensify there. There is no truce or hunger strike in Florida, and Zimmerman is embraced by the Aryan Brotherhood, fueling whatever racial ideas he has about the world and crystalizing them forever. Vilified by some and canonized by those who believe in maintaining the racial caste system in America, Zimmerman would become one more pawn in the battles fought across racial lines in the criminal justice system.

Many of the good, angry, upset, frustrated people who will be in the streets this afternoon protesting spend much of their time protesting the excesses of our prison system. If we believe, generally, that the hyperpunitive character of America’s incarceration project is destructive, dehumanizing, and ultimately counterproductive, then sending one more person, deserving as he may be, to this system is no cause for rejoice.

So, a guilty verdict would not send me frolicking in the streets. It would push me into solemn contemplation of the futility of remedying years of slavery, lynching, discrimination, with one “right” act. And mostly, into contemplation of the immense well of suffering that is to become Trayvon Martin’s family’s life for many, many days to come. Healing doesn’t come from a guilty verdict.

Where Healing Comes From

Nothing good comes from punitiveness, and it will not change what we know or think about the world. Healing comes from taking the rage and hot, burning energy we all feel this morning, and channeling it toward sentiments that produce effective change. It comes from taking a hard look at the immense resources we spend in maintaining a carceral colossus and investing them in educating a new generation of people who do not hate, suspect and judge others based on the color of their skin. That is the commitment I’d like to see renewed today, after our anger subsides and we start asking ourselves where to go from here.

Healing comes from a deeper understanding of the role of implicit biases in our own lives. From asking ourselves why one of Victor Rios’ young interviewees did not get a fast food joint job at an interview in which he refrained from shaking his prospective boss’ hand, not wanting to alarm a white woman with physical closeness. From asking why reaching out to others across skin color lines is such a frightening concept. From taking a cue from California inmates, who have realized that the unfair, torturous, abysmal incarceration conditions they face is a common enemy that transcends race and needs to be fought together.

“Sorrow is better than fear. Fear is a journey, a terrible journey, but sorrow is at least an arrival. When the storm threatens, a man is afraid for his house. But when the house is destroyed, there is something to do. About a storm he can do nothing, but he can rebuild a house.”

Alan Paton, Cry, the Beloved Country