In case you haven’t seen it yet, CURB’s realignment budgeting report card is an incredible data mine, with a wealth of info from 13 counties’ realignment plans. SF pass, LA incomplete, SD fail… this is a great visual metric of the degree to which counties are investing in new jail expansion plans versus alternatives and re-entry programs.

Rosenberg on Reentry: The Importance of Peers and Good Programs

In two recent NYT blog posts, Pulitzer prize awardee Tina Rosenberg reflects on the conditions for successful prisoner reentry.

Rosenberg’s first blog post mentions the meager release packages for inmates exiting correctional institutions and the lack of rehabilitative programs, but emphasizes the need to provide them with “a better class of friends”: People committed to AA meetings and GED classes, who will motivate them rather than drag them down the recidivist path. She mentions two programs: The Castle in New York, and San Francisco’s Delancey Street Foundation. Here is some of what she has to say about the latter:

People come to live at the Delancey Street residential building for an average of four years. Each resident is required to get at least a high school equivalency degree and learn several marketable job skills, such as furniture making, sales or accounting. The organization is completely run by its residents, who teach each other — there is no paid staff at all. Teaching others is part of the rehabilitation process for Delancey residents. The residence is financed in part by private donations, but the majority of its financing comes from the businesses the residents run, such as restaurants, event planning, a corporate car service, a moving company and framing shop. All money earned goes to the collective, which pays all its residents’ expenses.

. . .

The Delancey Street residence, which began in 1971, has never been formally evaluated. But there is no question that is phenomenally successful. It has graduated more than 14,000 people from prison into constructive lives. Carol Kizziah, who manages Delancey’s efforts to apply its lessons elsewhere, says that the organization estimates that 75 percent of its graduates go on to productive lives. (For former prisoners who don’t go to Delancey, only 25 to 40 percent avoid re-arrest.) Since it costs taxpayers nothing, from a government’s point of view it could very well be the most cost-effective social program ever devised. The program has established similar Delancey Street communities in Los Angeles, New Mexico, North Carolina and upstate New York. Outsiders have replicated the Delancey Street model in about five other places.

. . .

There are two puzzles here. Delancey Street is now celebrating its 40th anniversary. One would think that by now there would be Delancey 2.0 models sprouting all over. But there are not. A related mystery concerns the idea that underlies both Delancey and the Castle: the importance of pro-social peers. Our guts tell us they matter; we know the effect our friends can have on our behavior. Peer pressure may be the single most important factor getting people into crime — surely it should be employed to get them out again. Yet it is not. Besides Delancey and the Castle, there is probably not a single government agency or citizen group working with former prisoners that lists “clean-living peers” alongside housing, job training and other items on its agenda for what former prisoners need to go straight.

The second blog post expands upon the reasons for reentry failure. Citing David Kirk’s interesting research on the decline in recidivism following Hurricane Katrina, Rosenberg points out how important it is to maintain places that provide support and encounters with reentering peers. She mentions initiatives like Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles, and attributes their inadequate-to-nonexistent funding to “tough on crime” political rhetoric and to lack of research showing the decline in recidivism. However, there are grounds for hope, including humonetarianism (a discourse of scarcity that creates a countereffect to punitive policies) — the silver lining of the financial crisis:

The good news is that we may have reached a turning point, a chance at last to see effective anti-crime policies edge out ineffective ones. One reason is the record number of people being released from prison. This has made prisoner re-entry a hot topic in the field of corrections (if still invisible to the rest of the world). The politics, too, have changed. The crime rate throughout the United States has dropped, which means that voters are less panicked about crime and less singleminded about harsh measures.

The public isn’t thinking about crime — but state officials are. States are in budget crisis. Many states are looking for ways to let nonviolent prisoners out — and they can’t afford to see them come back again. California’s three strikes law — your third felony conviction, even if for something minor, brings a 25-year-to-life prison term — is costing the state $500 million a year, according to the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Those costs will rise as the prison population ages as a consequence of the law — housing elderly prisoners can cost upwards of $50,000 per year per inmate. And elderly prisoners are the last people you want in prison, as they are the least likely to re-offend. States are finally getting interested in finding out what actually maximizes the chance that ex-offenders will become good citizens. They’re not going to be able to do that without financing research.

Rosenberg’s posts are a call to conduct empirical research on the recidivism-related implications of reentry programs. As we know, recidivism reports are very problematic. The dismal numbers in CDCR’s recidivism report do not necessarily reflect a “return to a life of crime” as much as they might reflect parole failures and technical parole violations (an aspect regarding which the Supreme Court has recently exhibited surprising naïvete). As this good summary from the NIJ website explains, recidivism is a difficult thing to measure. Studies examining the impact of reentry programs and changes in peer groups on recidivism should be careful in their findings. Assuming such problems can be tackled, funding should be provided to programs with proven effects on recidivism rates, such as the marine technology and carpentry training programs at CDCR.

————————

Props to Michael Sierchio for the link.

What’s He Building In There? Part III

More building plans come in the heels of the Michigan construction and the Calaveras and San Bernardino projects. These projects, however, seem to be more benign and have a reentry/therapeutic purpose. The CDCR website describes the three projects as follows:

Renovation and reuse of the former Northern California Women’s Facility in San Joaquin County as a 500-bed adult male secure community reentry facility pursuant to the mandates of AB 900, which envisioned this new type of correctional facility for inmates within 6-12 months of parole;

Renovation and reuse of the former El Paso De Robles Youth Correctional Facility in San Luis Obispo County (closed in 2008) as a 1,000-bed Level II adult correctional facility to be named the Estrella Correctional Facility, and

Renovation and reuse of the former Dewitt-Nelson Youth Correctional Facility in San Joaquin County (closed in 2008) as a 1,133-bed adult correctional facility with a mental health treatment mission.

LA Times favors parole for youth LWOPs

Today’s LA Times carries this piece: http://www.latimes.com/news/opinion/opinionla/la-ed-1208-sara-20101208,0,2931752.story subtitled, “Sara Kruzan’s case shows why juveniles should not sentenced to life without parole.”

The Times had previously written in favor of Sen. Yee’s narrowly-defeated SB 399 to change this policy statewide; today’s Times asks Governor Schwarzenegger to offer clemency, if only in this one extreme case.

My favorite quotes: “She has volunteered for dozens of rehabilitation programs and won awards for her participation and attitude. … The CYA felt that she should have been prosecuted as a juvenile rather than as an adult, which would have put her into a rehabilitation program from which she could have been freed by age 25 — seven years ago.”

Sentenced a minor to life behind bars with no chance of parole is a ghastly, inhumane, cruel practice.

Recidivism Discussion on KGO

Yours truly was on the radio this week, speaking to Gene Burns on the Gil Gross show, about the CDCR recidivism report. Listen here.

CDCR Recidivism Report

CDCR has just released its recidivism report, which is fairly detailed and merits some discussion. First, I think these reports are a good start and CDCR should be commended for tracking down the information and analyzing it. The Office of Research did an overall good job at highlighting some of the major issues and, while I’m sure more could be mined from the raw data, there is enough content to comment on.

Here are some points that come to mind, in no particular order:

The recidivism rates in general, while not surprising, are disheartening, and attest to the complete failure of our prison system in achieving deterrence, rehabilitation, or both. It is telling that the statistics haven’t changed significantly over time, despite increased punitive measures. Clearly, what we are doing under the title “corrections and rehabilitation” does not correct OR rehabilitate. The percentages are particularly distressing for people who have been incarcerated at least once before.

Some interesting demographics: The report tracks people up to three years after release. Almost 50% reoffend within first six months; at one year, the percentage rises to 75%. Women recidivate at much lower rates than men (it would help to have a breakdown of this by offense, because perhaps offense patterns matter here). Unsurprisingly, recidivism declines with age. Also, recidivism rates for first-time offenders are highest for Native Americans, African Americans, and White inmates. But these effects dissipate for re-releases.

The releases from prison are unevenly distributed across counties (a large percentage of released inmates goes to LA). However, most of the folks that end up in LA are first-time releases, which explains why the recidivism rate in LA is actually the lowest. Other counties, such as SF, Fresno, and San Joaquin, have the highest recidivism rates, but they receive re-releases (for whom the rates are higher in general) more than first-time releases.

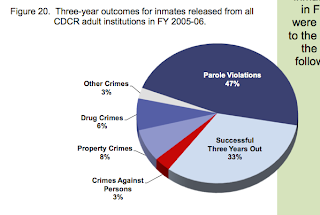

The distribution of offenses is interesting. 20% of released inmates were in for serious/violent crimes, and this percentage holds for recidivism, so it would appear that people do not “graduate” to more serious crime (perhaps they just do more of the same). Also, there doesn’t seem to be a connection between seriousness of crime and recidivism (which might suggest that it’s the institutionalization that contributes to it). Also, the report doesn’t track a connection between the original offense and the re-offense, save for sex offenders. Notably, however, 47% of returnees to prison are brought back in because of parole violations.

Re sex offenders:

This category merits special attention because it’s the one most often targeted by punitive legislative energy. 6.5% of released people registered as sex offenders. The data suggests that sex offender registration slightly reduces recidivism. However: Only 5% of released sex offenders who recidivate are convicted of an actual sex offense. 8.6% commit an unrelated crime, and 86% are back on a parole violation. This speaks volumes about the pervasiveness of registration rules and limitations and about the low risk of sex offenders.

More than half of the released inmates are in for short sentences – but for recidivists the length of sentence grows (this is probably just the effect of previous offenses enhance sentencing or of repeated parole violations.) There is a rise in recidivism for people who serve 0 to 24 months. After that, the rates decline. Possible intervening variables are health and age.

Recidivism rates rise significantly for folks released after their second incarceration (although subsequent re-incarcerations don’t make much of a difference). The returnees are also more likely to be assigned a high “risk score”. These two findings are not unrelated; I imagine that, when using the CSRA tool for predicting recidivism, one predictor of “high risk” is repeated prison sentencing. This classification therefore probably feeds itself.

On a more general note, I hope that releasing the data also means that our judicial apparatus might rethink some of its policies and approaches. In Malcolm Feeley and Jonathan Simon’s 1992 piece The New Penology, they argue that our “actuarial” approach to justice is behind a transformation from external correctional goals (e.g. reducing recidivism) to internal goals (e.g. reduce riots and escapes). If someone is keeping track of recidivism data, let us hope that the data actually gets used.