Today at Hastings we had the pleasure of hosting Laurel Kaufer, founder of Prison of Peace, a unique program at Valley State Prison for Women in Chowchilla, CA. At the initiative of Susan Russo, one of the inmates, who sought to alleviate the violence in her immediate environment, fifteen women were trained in mediation skills and received mediation certification. Some of these women proceeded to become trainers, and now a hundred and fifty women in prison have skills that enable them to help others process conflict in healthy, empathetic ways. Prison authorities report a calmer, less violent prison. What a wonderful thing it is to provide people in a stressful, violent environment the skills they need to resolve conflicts, conduct peace circles, and listen attentively to others.

CURB Realignment Report Card: Grades are in!

In case you haven’t seen it yet, CURB’s realignment budgeting report card is an incredible data mine, with a wealth of info from 13 counties’ realignment plans. SF pass, LA incomplete, SD fail… this is a great visual metric of the degree to which counties are investing in new jail expansion plans versus alternatives and re-entry programs.

Haney on Psychological Consequences of Imprisonment in California

Today I attended a compelling lecture by Dr. Craig Haney of UC-Santa Cruz on the individual psychological consequences of imprisonment in California. His talk was especially well-timed after Dr. Haney was cited six times by the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Brown v Plata. You may also recognize Dr. Haney as the lead author of the famous Stanford prison study from 1973, in which twenty healthy males, evenly divided into groups of “inmates” and “guards,” acted so brutally that the 2-week experiment was suspended after 6 days.

Since then, Dr. Haney has spent over 30 years touring and studying prisons and prisoners. He began with an overview of the recent expansion of the U.S. prison system, because overincarceration has led to Plata and “prisonization” (stay with me here). The U.S. rate of imprisonment stayed stable around 200,000 from World War I to the mid-1970s, when the War on Drugs sentencing mentality started. From 1973-1993, the CA crime rate hovered around 100 per 100,000, but the incarceration rate increased from 100/100,000 to 350/100,000.

Dr. Haney pointed out that, being a generation older than me, he could still remember a time when prisoners had their own cells. Cellmates, or double-celling, was still seen as an abomination in the mid-1970s. His archives include letters from the prison wardens of 40 years ago, decrying this inhumane practice. Now, of course, prison cells house at least two inmates as a matter of course.

Prison used to aim to rehabilitate prisoners. Through work assignments, education, and other programs, inmates were taught useful skills or conditioned for better lives. In the mid-1970s, states began to veer away from this century-old aim: Haney referred us to Cal. Penal Code § 1170(a)(1), passed in 1976, which begins: “The Legislature finds and declares that the purpose of imprisonment for crime is punishment.” Half of CA prisoners released in 2006 had had no assignment whatsoever: no program, no job, no education. All those years, wasted. In 1973, prisoners averaged a 6th-grade reading level, and this is still the same today.

As recently as the 1970s, people suffering from serious mental health conditions were usually committed to mental hospitals for in-patient treatment. Nowadays, mental health patients are more commonly imprisoned. In the U.S., the rate of hospitalization of mental health patients has fallen from 450 per 100,000 residents over 15 years old in 1950, to only 50/100,000 in 1990. People who would be hospitalized in 1950-1980 are more commonly incarcerated in 1980-2010.

Dr. Haney used this background to discuss institutional history as social history. By taking over so many people’s lives, for so long, commonly at such young ages, the state has become not only a parent, but an abusive parent. Imprisonment retraumatizes inmates who have already experienced the trauma that led to their incarceration in the first place. Prisoners suffer tremendous institutional risk factors: abuse, maltreatment, neglect, an impoverished environment, diminished opportunities, exposure to violence, abandonment, instability, and exposure to criminogenic role models.

Haney’s last slide explained “prisonization” as a set of normal psychological responses to abnormal situations. Prisons create dependence on institutional structures and procedures: newly-released people may suffer a lack of volition and independence as they are separated from these strict regimens. Prisons damage interpersonal skills or even prevent future relationships, by engendering interpersonal distrust, “hypervigilance,” suspicion, emotional overcontrol, alienation, psychological distancing, social withdrawal, and isolation. Prisons diminish self-worth and personal value, and can result in Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder — PTSD inflicted by slow, continuing trauma as opposed to a discrete event.

Krenwinkel Denied Parole: Some Questions on Remorse

(Image courtesy AP and the Sac Bee)

This is a crime children grow up hearing about,” said parole commissioner Susan Melanson. She said they had received 80 letters from around the world advocating Krenwinkel’s continued incarceration. “These crimes remain relevant.”

Krenwinkel, now gray haired and grandmotherly looking at 63, wept and apologized.

“I’m just haunted each and every day by the unending suffering of the victims, the enormity and degree of suffering I’ve caused,” Krenwinkel said.

She was soft spoken and contrite in response to board members’ questions, describing the downward spiral of her life after she met Manson and came under his spell.

“He sang to me and made love to me,” she said. “…I left everything and went with him. He seemed like the answer to my salvation.”.

Because of him, she said, “Everything that was good and decent in me I threw away.”

It was her late father, she said, who helped her realize during his visits to her in prison, “what had happened, and the monster I became.”

And here’s the response from the prosecutor and victims:

“If Patricia Krenwinkel has remorse, I don’t see how she could walk into this room,” said a tearful Anthony Di Maria, the nephew of Jay Sebring, who was killed along with Tate. “No punishment could atone for the cold-blooded murders in this case.”

Los Angeles Deputy District Attorney Patrick Sequeira also suggested that if Krenwinkel was remorseful she would waive her parole hearings and accept her punishment.

These are interesting comments. They suggest that, for someone convicted of a truly heinous crime, there is no way to show remorse except not showing it and accepting one’s punishment. That is, that showing remorse and seeking release from imprisonment are incompatible. Setting aside the particulars in Krenwinkels’ case, this premise seems to evoke the religious undertones of the original penitentiary – seeing the prison as an institution for understanding the full meaning of one’s bad deeds and redeeming one’s soul through serving one’s time. These goals shaped the American prison from its early days; the isolation method at Eastern State Penitentiary (which we visited in late 2009), with no one to talk to except for the pastor and nothing to read but the Bible, were designed by Quaker reformer with those exact aims in mind.

LA Times favors parole for youth LWOPs

Today’s LA Times carries this piece: http://www.latimes.com/news/opinion/opinionla/la-ed-1208-sara-20101208,0,2931752.story subtitled, “Sara Kruzan’s case shows why juveniles should not sentenced to life without parole.”

The Times had previously written in favor of Sen. Yee’s narrowly-defeated SB 399 to change this policy statewide; today’s Times asks Governor Schwarzenegger to offer clemency, if only in this one extreme case.

My favorite quotes: “She has volunteered for dozens of rehabilitation programs and won awards for her participation and attitude. … The CYA felt that she should have been prosecuted as a juvenile rather than as an adult, which would have put her into a rehabilitation program from which she could have been freed by age 25 — seven years ago.”

Sentenced a minor to life behind bars with no chance of parole is a ghastly, inhumane, cruel practice.

David Onek for SF DA?

Now that Kamala Harris is officially moving up from SF District Attorney to CA Attorney General, there will be a hotly contested election for a new District Attorney here in San Francisco in November 2011. One leading candidate is David Onek, a former member of the SF Police Commission; see http://www.davidonek.com/about

In a post on Calitics last month stumping for Kamala Harris, Mr. Onek embraced the humonetarian view of criminal justice, leading with financial statistics about the expense of recidivism. Onek applauds Harris’s Smart on Crime approach, and in particular the Back on Track program. Overall, the post suggests Onek supports more money for prevention, intervention, and rehabilitation, and less money for useless re-incarceration. Tellingly, Onek’s candidacy for SF DA was recently endorsed by Jeanne Woodford, the reform-minded former director of CDCR who supported Prop 5 in 2008.

Facebook users have the opportunity to support David Onek’s campaign for DA by clicking “Like” at http://www.facebook.com/DavidOnek

Retributivism and Restorative Justice

The afternoon panels at CELS also featured wonderful work. First I heard Dena Gromet and John Darley’s paper Gut reactions to Criminal Wrongdoing: The Role of Political ideology. In the paper, Gromet and Darley examine whether people’s support for a retributive or restorative framework depends on reason considerations, or whether it is a gut reaction. To measure that, they conducted a survey in which they asked respondents’ opinions on victims and on offenders, assessing their support for each framework. They also inquired about their political opinion (on a conservative to liberal scale). To measure gut reactions, rather than calm reasoning, they asked respondents these questions under cognitive load (made them memorize an 8-digit number while they responded). They found that the satisfaction with restoration, whether on its own or as added to satisfaction with retributivism, goes up for liberals and down for conservatives with cognitive load. Their conclusion was, therefore, that liberals and conservatives have different intuitive reactions to serious crime: Liberals endorse restoration while conservatives favor retribution.

This paper was followed by Tyler G. Okimoto, Michael Wenzel and N.T. Feather’s paper Conceptualizing Retributive and Restorative Justice. Drawing on differences in conception of justice, Okimoto, Wenzel and Feather administered a survey in which they asked respondents a series of question to establish the extent to which they subscribed to two alternative views of justice: the need to empower the victim and degrade the offender, versus the need to heal relationships and reassert consensual social values. They generated a scale that allows measuring where respondents lie along a spectrum of retributive to restorative justice.

Incarceration Length and Recidivism

This morning at CELS I heard a paper by David Abrams titled Building Criminal Capital vs Specific Deterrence: The Effect of Incarceration Length on Recidivism. Abrams sought to figure out what sort of relationships existed between incarceration and recidivism. These sort of studies often present serious challenges, because length of incarceration might reflect other factors about the defendants that might predict recidivism later on. However, Abrams built on an opportunity to control for that, since defendants were randomly assigned to public defenders of differing attorney ability. Attorney ability therefore allowed him to instrument for sentence length. The findings were that the relationship between sentence length and incarceration was not linear. For the lowest sentences, the relationship is negative; it becomes positive for an intermediate sentence length, and then negative for the longest sentences. The conclusions tie the findings with theories of criminal capital formation and with specific deterrence.

CDCR Recidivism Report

CDCR has just released its recidivism report, which is fairly detailed and merits some discussion. First, I think these reports are a good start and CDCR should be commended for tracking down the information and analyzing it. The Office of Research did an overall good job at highlighting some of the major issues and, while I’m sure more could be mined from the raw data, there is enough content to comment on.

Here are some points that come to mind, in no particular order:

The recidivism rates in general, while not surprising, are disheartening, and attest to the complete failure of our prison system in achieving deterrence, rehabilitation, or both. It is telling that the statistics haven’t changed significantly over time, despite increased punitive measures. Clearly, what we are doing under the title “corrections and rehabilitation” does not correct OR rehabilitate. The percentages are particularly distressing for people who have been incarcerated at least once before.

Some interesting demographics: The report tracks people up to three years after release. Almost 50% reoffend within first six months; at one year, the percentage rises to 75%. Women recidivate at much lower rates than men (it would help to have a breakdown of this by offense, because perhaps offense patterns matter here). Unsurprisingly, recidivism declines with age. Also, recidivism rates for first-time offenders are highest for Native Americans, African Americans, and White inmates. But these effects dissipate for re-releases.

The releases from prison are unevenly distributed across counties (a large percentage of released inmates goes to LA). However, most of the folks that end up in LA are first-time releases, which explains why the recidivism rate in LA is actually the lowest. Other counties, such as SF, Fresno, and San Joaquin, have the highest recidivism rates, but they receive re-releases (for whom the rates are higher in general) more than first-time releases.

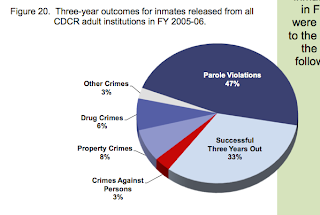

The distribution of offenses is interesting. 20% of released inmates were in for serious/violent crimes, and this percentage holds for recidivism, so it would appear that people do not “graduate” to more serious crime (perhaps they just do more of the same). Also, there doesn’t seem to be a connection between seriousness of crime and recidivism (which might suggest that it’s the institutionalization that contributes to it). Also, the report doesn’t track a connection between the original offense and the re-offense, save for sex offenders. Notably, however, 47% of returnees to prison are brought back in because of parole violations.

Re sex offenders:

This category merits special attention because it’s the one most often targeted by punitive legislative energy. 6.5% of released people registered as sex offenders. The data suggests that sex offender registration slightly reduces recidivism. However: Only 5% of released sex offenders who recidivate are convicted of an actual sex offense. 8.6% commit an unrelated crime, and 86% are back on a parole violation. This speaks volumes about the pervasiveness of registration rules and limitations and about the low risk of sex offenders.

More than half of the released inmates are in for short sentences – but for recidivists the length of sentence grows (this is probably just the effect of previous offenses enhance sentencing or of repeated parole violations.) There is a rise in recidivism for people who serve 0 to 24 months. After that, the rates decline. Possible intervening variables are health and age.

Recidivism rates rise significantly for folks released after their second incarceration (although subsequent re-incarcerations don’t make much of a difference). The returnees are also more likely to be assigned a high “risk score”. These two findings are not unrelated; I imagine that, when using the CSRA tool for predicting recidivism, one predictor of “high risk” is repeated prison sentencing. This classification therefore probably feeds itself.

On a more general note, I hope that releasing the data also means that our judicial apparatus might rethink some of its policies and approaches. In Malcolm Feeley and Jonathan Simon’s 1992 piece The New Penology, they argue that our “actuarial” approach to justice is behind a transformation from external correctional goals (e.g. reducing recidivism) to internal goals (e.g. reduce riots and escapes). If someone is keeping track of recidivism data, let us hope that the data actually gets used.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The Good

This comes to us via our friends at the Prison Law Blog: A meditation program in San Quentin.

The Bad

Governor Schwarzenegger vetoes AB 1900, which would prohibit the shackling of pregnant inmates. The reason? “CSA’s mission is to regulate and develop standards for correctional facilities, not establish policies on transportation issues to and from other locations. Since this bill goes beyond the scope of CSA’s mission, I am unable to sign this bill”.

The Ugly

The state has now restocked on sodium thiopental.