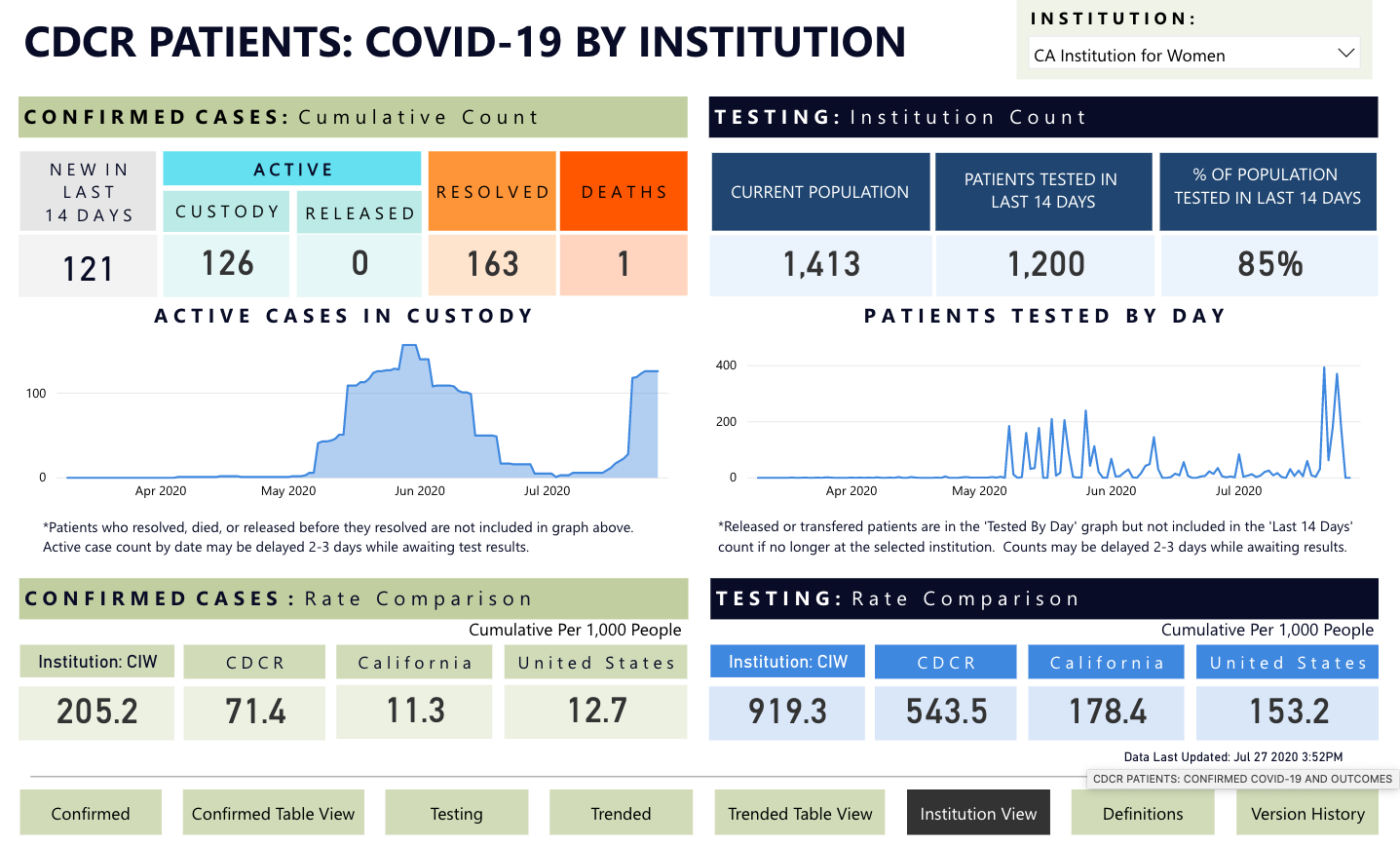

After a spike in early June and an apparent abatement, COVID-19 is once again tearing through the California Institute for Women (CIW) in Chino. In the last 14 days, the prison tested 1,200 of its 1,413 residents (housed in a facility designed to hold 1,398 people – slightly above 100% capacity.) The testing count on the tracking tool seems to suggest testing done in batches, but we don’t know how they are managing isolation in a crowded facility–hopefully not taking a page from the book of this women’s prison in Texas.

CIW is of special interest to me, because a few days ago we learned that Leslie van Houten, who is serving her sentence there, has been yet again recommended for parole. Van Houten has been consistently recommended for parole since 2017, but governors–first Brown, now Newsom–keep reversing the recommendation for what seems to me, after having pored over 50 years’ worth of her prison record, purely political reasons. Van Houten has maintained a clean disciplinary record, participated in a variety of laudable programs, and incessantly excavated her psyche to show “insight” to the Board. She participated in the murders when she was 19 years old, manipulated and sexually exploited in a setting that, with today’s #MeToo sensibilities, might have shed a completely different light on her involvement.

I mention van Houten’s case because it is emblematic of the dilemma that Gov. Newsom faces with countless other cases. The right thing to do is to release older prisoners, who are more vulnerable to the virus; these people, who serve long sentences, are serving them for violent crimes they committed decades ago. Everything we know about life course criminology supports the prediction that they pose no risk to public safety–they themselves face a risk by remaining behind bars.

In Yesterday’s Monsters I explain how the Manson family cases came to shape California’s extreme punishment regime, and how these cases were impacted by this new regime in turn. This is the chance for a politician who has consistently ran, and prevailed, on a platform of doing the right thing in the face of baseless political pressures. There is no ambiguity about the right thing to do now. Van Houten is 70 years old, has been consistently found to pose very low risk to public safety by actuarial instruments and by everyone who has interacted with her, and there’s a pandemic going on.

Van Houten is not the only person at CIW facing these risks. Just a few days ago, advocates were overjoyed to welcome home Patricia Wright, a 69-year-old cancer patient who doctors say has mere months to live, after she served 23 years in prison. Wright’s release encouraged me, given the infuriating and heartbreaking scene just eleven years ago at Susan Atkins’ last hearing. Perhaps the pandemic is driving home, finally, the message that allowing an older person to die at home with their loved ones, or live out in peace the few years they have left, is not a weakness, nor a slight to the victims. Perhaps it is driving home the message that compassion is an essential component of our humanity. Will Gov. Newsom choose to do the right thing for van Houten and other women at CIW, from both public health and public safety perspectives, or will he succumb to unfounded public pressure, hysteria, and fear?