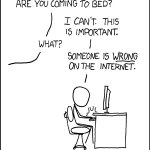

| A Jewish folk story I know goes like this: A farmer lives in a house with his wife and children and the grandparents, and it is so noisy that he thinks he will go crazy. He goes to the Rabbi for advice. The Rabbi says, “bring your goat into the house.” The farmer says, “but that’ll just make everything worse!” The Rabbi says, “do as I say.” The farmer, skeptical but trusting the Rabbi’s wisdom, brings the goat in. A week later, the man returns to the Rabbi, who asks him, “how’s it going?” The man says, “it’s so much worse! We are so crowded and the goat is pooping everywhere and eating our food!” The Rabbi nods and says, “now, take the goat out of the house.” Upon hearing that the beach closures will only cover Orange County–the specific beaches where overcrowding and noncompliance were visible on the weekend–I felt very relieved and happy despite not having actually gained or lost anything. It occurs to me that this is a great illustration of Kahneman and Tversky’s work on the entitlement effect. The entire emotional rollercoaster was a fascinating study in comparisons and tribalism. When we were threatened with the closures, I felt anger toward local government (“how can they take this away from my child?!”), at the Orange County beachgoers (“this is why we can’t have nice things!”) at friends who disagreed with me; in short, at “others”, a-la Sartre’s “Hell is other people.” Our powerful teacher, COVID-19, has given us plenty of opportunity to develop and espouse strong opinions about other people: how they are handling the pandemic, how their situation compares to ours… in other words, a lot of dividing the world into “us” and “them.” Kanheman and Tversky’s work is so helpful for understanding the formation of these aggressively negative opinions. Cognitive bias conditions us to notice and retain evidence that’s consistent with our views. And we tend to not notice or reject evidence that doesn’t support our views (e.g., we are disgusted with one racist post, deduce that “Nextdoor is full of racists,” and ignore the dozens of kind, helpful posts.) Attribution error makes us explain people’s behavior in different ways based on whether or not we like them: If it is an enemy of ours, and they do something good, then we attribute it to circumstances, the situation. When they do bad things, we attribute their behavior to their disposition. With friends, it is the other way around (e.g., a friend is well prepared and provides for their family by shopping extensively; a stranger, or someone I dislike, is a selfish hoarder.) Harvard ethicist Herbert Kelman writes: “Attribution mechanisms . . . promote confirmation of the original enemy image. Hostile actions by the enemy are attributed dispositionally, and thus provide further evidence of the enemy’s inherently aggressive, implacable character. Conciliatory actions are explained away as reactions to situational forces—as tactical maneuvers, responses to external pressure, or temporary adjustments to a position of weakness—and therefore require no revision of the original image.” Theologist Robert Wright, who has looked at the connection of Buddhism and modern psychology, observes that a big part of the formation of essence involves feelings. There is a lot of evidence now in psychology that when we look at any person, we react to some extent at the level of feeling, and then that shapes the way we behave towards that person With people, feeling is so critical to perception that the very identification of people depends on feelings in ways more subtle than we are normally aware of. Feelings are at the core of the comparing mind. Leon Festinger posits that we compare ourselves to people we perceive to be worse than we are (less moral, less good, less worthy) to increase our self esteem. Much of the debate over compliance and social distancing policy divides people into camps: Who has it easier? People with kids? People sheltering alone without kids? People sheltering with someone they don’t get along with? Does the age of the kids matter? If your comparing mind is in overdrive–mine sure has been, and I’m seeing a lot of evidence around me that it’s not just me–start by having some compassion for yourself. Comparing is part of the human experience. Second, the inchoate fear and anger in your mind will invariably look to hook onto something concrete. It may or may not be a righteous coat hanger. But it is a coat hanger, and we have to see it in order to sit with it. How to address the comparing mind: Byron Katie’s work, which I have a complicated reaction to, involves examining limiting thoughts. You can use her Judge Thy Neighbor worksheet to examine rigidly held opinions about others. Using practices of self compassion and compassion for others, such as Krisin Neff’s exercises, can also be very helpful, as can this wonderful exercise from Rick Hanson called “drop your case.” In general, anything that frees your mind from a zero-sum-game is going to be a healthy way to look at things. Resources may be finite, but joy and kindness are not (and neither is suffering)–so focus on that. |

1 Comment

[…] couple of weeks ago I posted about the comparing mind and how to soften our judgment of others. The pull toward judgment is so strong–I’m […]