Media attention has thankfully shifted to COVID-19 outbreaks in prisons, focusing, understandably, on the horrific crisis unfolding in San Quentin. Yesterday’s KTVU story (below) and another one at The Appeal are a step in the right direction (also, today at 5pm KALW will broadcast an interview in which I explain some dimensions of the problem.)

I think it’s important, though, to perceive what is happening not just at the individual prison level, but on a systemic level, and through the lens of organic connections between prisons and the surrounding community. Which brings us to the site of some recent rises in infections: prisons in Kern County.

A few important things to know about Kern County: Just by looking at the CDCR tracking tool, you’d think that there are four prisons there – California Correctional Institution (CCI), Kern Valley State Prison (KVSP), North Kern State Prison (NKSP), and Wasco State Prison (WSP). But there’s a fifth one, California City Correctional Facility (CAC). The story of CAC explains a lot about the dynamics of California corrections. It was originally built in 1998 on speculation by Correctional Corporation of America (CCA), now rebranded in its gentler, kinder image as CoreCivic. By contrast to CCA’s wild success nationwide, it was unable to open a private prison on California soil because our powerful prison guards’ union, the CCPOA, resisted. Think about it as a Terminator-vs.-Godzilla epic fight: as Josh Page explains in his book The Toughest Beat, the union was so powerful that it beat the private contractors. The facility lay empty until 2006, when it was used as an ICE detention center (this was part of the “portfolio investment diversification” I talk about in Cheap on Crime.) But in 2013, as part of the state’s difficulty complying with the Plata population reduction mandates, they leased CAC from CCA, and it remains a privately-owned, state-run facility–confirming the speculative strategy of CCA, encapsulated in “if you build it, they will come.” I don’t know why the CDCR tracking tool does not provide information about CAC, and if you do, please email me–if there are people incarcerated there under CDCR management, their health is as important as that of people in state-owned facilities.

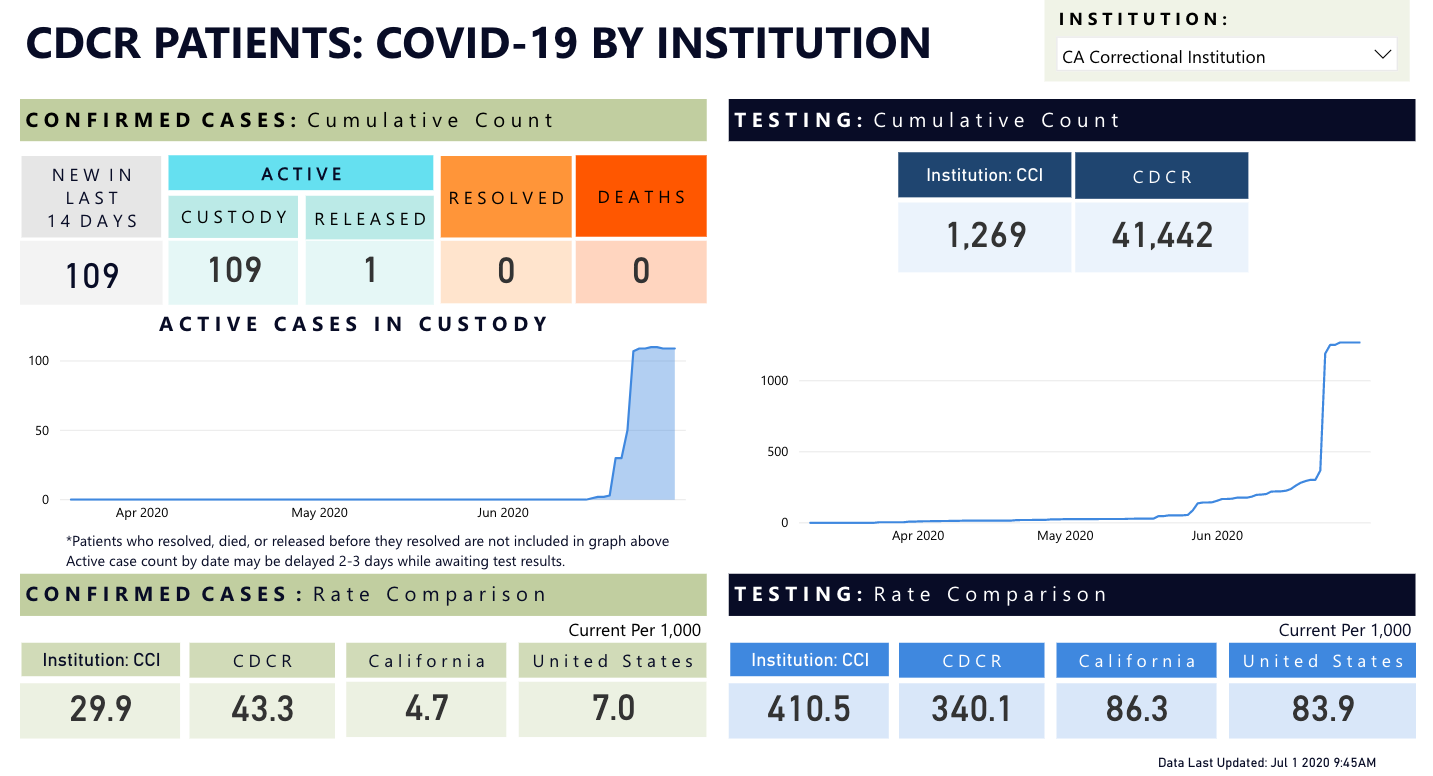

Let’s talk about what we do know. California Correctional Institution (CCI) started seeing cases on June 16. There are now 109 cases (there were 110; one person was released) and they have tested 41% of their population of 3,655 prisoners. Their infection rate is, therefore 7% of their tested population, and with an overcrowding of 131.3% as of last count, this could become a more serious problem.

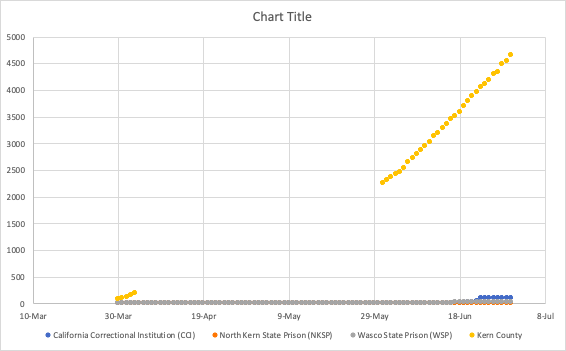

Kern Valley State Prison (KVSP) has no cases at all (here’s hoping that, barring staff carriers or more botched transfers, it will stay that way), but North Kern State Prison (NKSP) has a few. They had one isolated case in late March, which resolved itself in April, and on June 3 they had one case. They currently have five. They have tested 18% of their population, so there are probably more, and they are at 107.3% capacity.

The situation at Wasco State Prison (WSC) seems more recent. They currently have 24 cases; the first five were diagnosed June 1st. Again, they have only tested 13.5% of their population, so it’s hard to say how things might evolve. They are at 109.7% capacity.

I’ve looked at the corresponding numbers in Kern County, and there doesn’t seem to be a corresponding spike. In fact, contagion Kern County is an ongoing disaster regardless of what happens at the prisons–their infection rates has been rising, unabated, since March. You can see the overall county picture in yellow in the graph below; the county numbers are dwarfing the prison numbers, even though the latter, in themselves, seem significant.

As I’ve explained before, it is impossible to tell airtight causal stories based on these graphs without careful contact tracing. Nonetheless, it seems like what is happening in prisons there is a consequence of excessive reopening countywide: their restaurants and bars are open for indoor dining, as are their gyms, salons, and tribal casinos, to name just a few. The L.A. Times page for Kern County offers another dimension to the story: a tragic focal point of infections there is their nursing homes which, like prisons, are vulnerable to contagion once the virus is introduced from outside. It seems more probable, then, that infection in Kern County prisons is attributable to staff who live, shop, dine, or gamble in the county. The imperative seems to be to avoid transferring anyone into Kern Valley and to release everyone over 50 or otherwise immunocompromised/vulnerable.

1 Comment

[…] increase in new cases (seen in this graph as linear). A classic exam is Kern County, which we looked at a few days ago. Kern is a relatively open county with low levels of shelter-in-place compliance, and it’s […]