Shortly after newspapers broke the story of expected releases, a press release from CDCR unpacked the particulars of the expected plan to release about 8,000 people from California prisons. The press release frames these expected releases as a continuation of previous releases of 10,000 people. Before diving into the particulars of the plan, it is worth noting that no mass release of 10,000 people occurred; rather, the strategy for releasing 3,500 people (and more around the edges) was built on letting go of people who had very little of their sentences left, many of whom would have been out by now anyway.

The current plan is more of the same: it feels like the Governor’s office and CDCR officials are trying to navigate the tricky terrain between curbing the pandemic and producing a plan that will not result in too much public backlash, and are doing so by trimming the prison population at the margins, rather than cutting a slice from the middle of the population cake and causing controversy. The plan can be summarized into five points:

- 4,800 of the candidates for release are people who have 180 days left and are not doing time for violence or domestic violence, or registered as sex offenders.

- An undetermined number of people would be released if they have a year left on their sentence and are doing time for a nonviolent, nonsex crime at an outbreak epicenter: San Quentin State Prison (SQ), Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF), California Health Care Facility (CHCF), California Institution for Men (CIM), California Institution for Women (CIW), California Medical Facility (CMF), Folsom State Prison (FOL) and Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility (RJD). Those aged 30 and over are immediately eligible; younger people will be reviewed case-by-case by CDCR.

- CDCR is offering a 12-week programming credit to everyone not on death row or serving life without parole who doesn’t have a serious violation on their record since March 1. “Serious rules violations” range from murder to possession of a cellphone. This category encompasses 108,000 people, out of which 2,100 would advance to the point of being eligible for release this summer.

- CDCR defines people as medically “high risk” if they are over 65 with chronic medical condition, or with respiratory illnesses. Those of them assessed as low risk for violence who are not on death row, serving life without parole, or high-risk sex offenders, will be assessed for release on an individual basis.

- CDCR will also assess for release people in hospice or pregnant, and expedite release for people who have been granted parole (including the governor’s approval.)

Before pointing out the downsides of this plan, I think it is important to be aware of its upsides. There will be people getting out sooner than expected, and if only one of those people is saved from COVID-19 illness and death, that in itself is a big blessing to that person and their family. Many families will welcome their loved ones back, and the rolling basis, albeit not ideal from a pandemic prevention perspective, might allow some folks to better plan their future on the outside, especially against the backdrop of a terrible economy.

Still, the plan is insufficient for real relief:

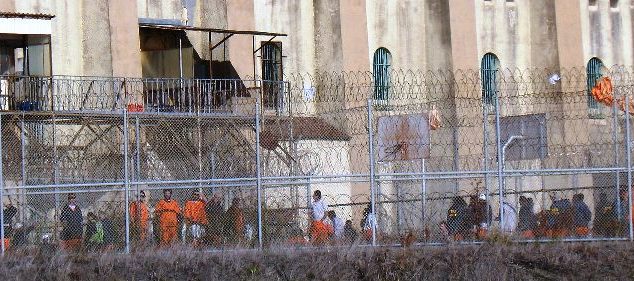

Too little. 8,000 is still a mere drop in the bucket–it is 6% of the current prison population of approximately 125,000. A more drastic cut is required systemwide, and in some places, much more drastic. To give you a sense of what is needed, the medical report from UCSF and UC Berkeley recommended that, due to San Quentin’s age and decrepitude, the population there specifically be reduced to 50% of current capacity. Thinking beyond San Quentin, the latest population count from July 8 puts 26 facilities–24 for men, 2 for women–at beyond design capacity, with nine of them morbidly overpopulated–above the 137.5% Plata standard (if they were to be applied per facility) and 10 more above 120% overcrowded. Releasing a total of 8,000 people does not even come close to allowing the kind of social distancing that would be necessary to halt pandemic spread.

Too late. A considerable chunk of the planned releases hinges on case-by-case evaluations, particularly for younger (under 30) people and for people at medical high risk. The time to carefully go over each person’s file was on March 1. At this point in time, I very much doubt CDCR has that luxury. A solid plan in the future will have to include more categorical releases akin to the credit plan.

Too reactive. CDCR developed a list of prisons where they will be releasing people who have a year or less left on their sentence, but the list–published yesterday–is already dated. A brief glance at the CDCR COVID-19 tracking tool reveals new outbreaks at several places, such new hot spots CCI and CRC. Also, keep in mind that several places that report apparent abatement in infections have brought their testing program to a grinding halt. As I explained yesterday, this means we do not have a true sense of where the pandemic is still active. The prisons listed in the press release already have a robust outbreak, and releasing vigorously from there, while helpful in terms of treating people, would not help with prevention.

Too sensitive to public backlash. Sharp-eyed readers have noticed the usual tropes: nonserious, nonviolent, nonsexual offenses. I feel like a broken record, but this apparently needs to be said again: There is no correlation between the crime of commitment and the risk to public safety. There is no correlation between the crime of commitment and the risk to public safety. Once more for the people in the back: there is no correlation between the crime of commitment and the risk to public safety. The emphasis on non-non-nons might have been tailored to obtain public buy-in, but it stubbornly evades dealing with the most obvious category of people for for release: folks doing life with parole for a crime (obviously violent) committed decades ago. My thoughts about how this catering to unfounded public hysteria harms people are not a big secret, and I explained them fairly clearly here. A short excerpt:

The math is simple. Out of the prison population, folks who were sentenced for a violent crime are the ones most likely to be (1) aging and (2) infirm. Aging, because the sentences are much longer; and infirm, because spending decades in a hotbed of contagion, with poor food and poor exercise options, does not improve one’s health. We know that a considerable portion of the health crisis in California prison is iatrogenic; not so long ago, Supreme Court Justices were horrified to learn that a person was dying behind bars every six days fo a preventable disease. So, a person who has spent decades in prison is more likely to be vulnerable to health threats. Such a person is also more likely to be older (by virtue of having been in prison for 20, 30, 40 years!) and therefore far less of a public risk of reoffending than a younger person who’s been inside for a few months for some nonviolent offense.

These folks, according to the careful typology by the Public Policy Institute of California, are a fourth of the prison population. If we were truly concerned about both reoffending risk and pandemic infection risk, they would be the obvious targets of a sound prison release policy. That they are not is not only something to be deeply regretted because of the risk to their health, but also a frustration because these folks, who get the worst press when released, are at such low risk of reoffending that parole officers I met when working on Yesterday’s Monsters expressed a strong preference for working with them.

The Governor and CDCR want to mitigate the medical catastrophe we are facing, and they are hoping that, by cobbling together palatable candidates for release, the numbers will somehow add up to sufficient prevention. They won’t. It’s a good start, and something to take pride in as activists, because I am sure that our constant pressure brought this about. But it is only a start, and much more needs to happen before we are even close to having a chance to save lives.

UPDATE: An edited version of this post appeared as an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle on July 15.

7 Comments

I don’t understand why aren’t looking at the men and women that been lock up for decades! They too deserve a second chance. Most of these people are mentors to youngsters in there. Also they’ve been programming and self programming especially in this pandemic of the COVID-19 virus. This System is corrupted!

Absolute Truth in every word. Thank you for speaking out facts

https://www.change.org/Letthemcomehome

Read this. It’s a petition to let Rehabilitated Lifers Come Home

The Board of Parole Hearings and Governor Newsom need to utilize their means of releasing people who won’t reoffend: finding those who are suitable for release and communtations.

[…] Unpacking CDCR’s COVID-19 Release Plan Hadar Aviram […]

[…] Hadar Aviram of UC Hasting School of Law, put it another way. (Aviram specializes in criminal justice policy, and writes regularly about California’s […]

[…] other experts condemned it as dangerously […]