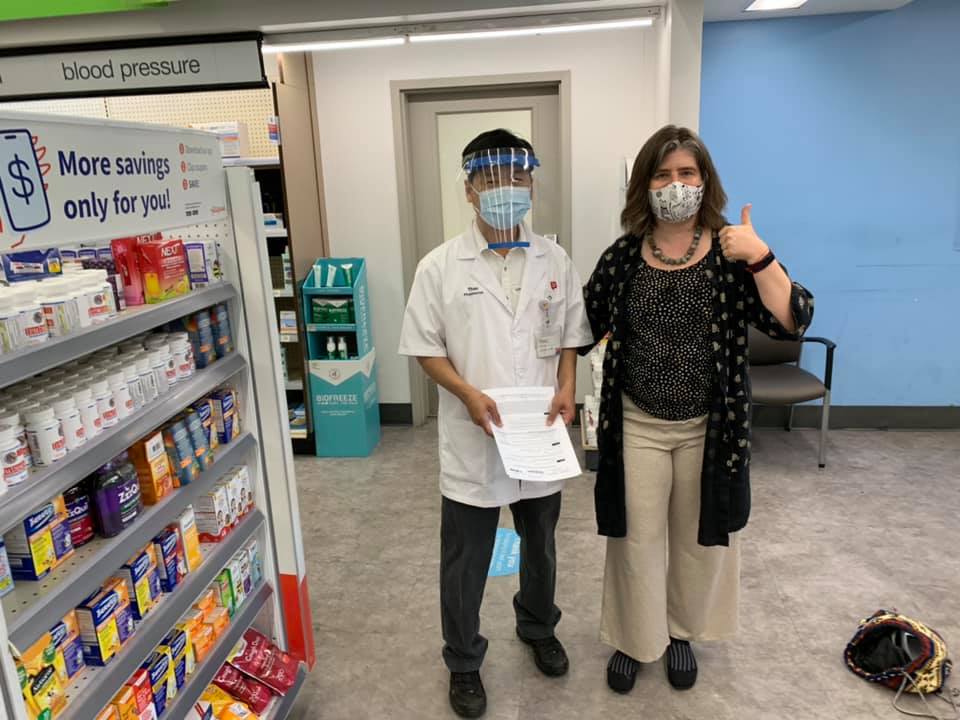

You guys, I got my first shot on Wednesday! That’s me in the picture with the fabulous pharmacist at the San Jose Walgreens who administered it. I can’t tell you how delighted I am to have gotten it. Hustling for an appointment was a tiresome project, and eventually I decided to trade distance for tenacity and drove out of town. Many places in the Bay Area vaccinate anyone who is lawfully entitled to be vaccinated in their county of residence, and thankfully educators are eligible in San Francisco, which means that, as of March 24, I’ll begin to hold office hours in person (in the open air, masked and distanced.) Hooray!

All around me, lots of questions and conundrums about how individuals fit in the vaccine equity struggle are floating about. Answers about ethics will differ from place to place and person to person. I’m no more an authority on ethics than Laura Schlessinger is on psychology, and Goodness knows the last thing we all need is more schoolmarmishness in our midst. However, in the off-chance you’re interested, my guiding principle in world improvement comes from Peter Singer’s effective altruism, as articulated in his excellent books The Life You Can Save and The Most Good You Can Do. I’m attracted to this philosophy because it makes an enormous amount of sense, and because it reinforces effectiveness over showmanship (as in: unless you have some special skills/qualifications, rather than personally flying out to eradicate malaria, keep your finance job and pay for *two* volunteers to eradicate malaria; if you want more diversity in law school, rather than organizing reeducation camps where privileged people publicly moan and grovel about their privilege, raise funds for scholarships for students from disadvantaged communities.)

I think the ethics of optimal philanthropy translate very well to the vaccine arena, where effective altruism must follow two important principles:

- Vaccination efforts are, by nature, not a zero-sum game (every person who gets vaxxed, even if it’s not us, benefits us because our odds of getting sick go down); and

- In a collective effort of this magnitude, there’s an important difference between individual actions and vaccine fairness in the aggregate.

From these two principles, flow the following four rules of thumb:

1. Is it your turn, according to the state/local protocols that govern eligibility wherever you are? TAKE IT. Is it lawful but you need to hustle for it (like click/refreshing aggressively for days or driving a bit farther)? HUSTLE AND TAKE IT. Your shyness/modesty/performative self sacrifice, as in “Others need it more than I do! Save Thyselves!” will not necessarily translate to any positive change in the world, as you have no control over who will get the vaccine in your stead. Your getting vaxxed benefits everyone around you.

1.1. First Corollary: If you think the rules where you live are inequitable, your one-person’s-quest to support a regime that you personally invented and think is equitable by opting out of the game does no one any favors (see above, individual vs. aggregate.)

1.2 Second corollary: Is there a population, group, or community who is being shortchanged by your local government’s plan? Take it when it’s your turn and ADVOCATE for the people who you think DESERVE priority (county jails! county jails! county jails!) Write letters to the editor, call your elected officials, organize a vaccine advocacy group on behalf of that community.

1.3. Third Corollary: Did you take it when it was your turn? LOUDLY ADVERTISE THAT YOU ARE VAXXED and encourage others to do the same when it’s their turn, which helps the collective effort more than your sacrificial protestations.

2. If it’s not your turn, DON’T JUMP THE LINE by engaging in deception (rule of thumb: If you’d be ashamed to admit on social media how you came to get the vaccine, don’t get it.)

3. The only exception to (2) is when you are being authoritatively encouraged to take it to prevent waste. The vaccine is precious and expensive; unrefrigerated Pfizer shots going into your arm are better than unrefrigerated Pfizer shots going in the trash. If outreach into a particular community is unsuccessful, and the word is out to show up at the end of the day to get the leftover doses in your arms (happens a lot in Israel) you are not taking shots away from the community in question; you are saving them from oblivion. By getting vaxxed yourself and publicizing it you are indirectly benefiting everyone, including the community in question.

4. Has someone in your immediate surroundings engaged in deception to obtain their shot out of turn? First, ask yourself whether there might be something you’re not privy to: you don’t know every person’s medical history, preexisting conditions and risks. Assuming you know there’s been ugly behavior, consider the difference between individual behavior and aggregate effects: even their unethical behavior indirectly benefits you and everyone else, and you are in no position to assess whether that benefit exceeds the cost of their deceit. You can stay friends with them, or not, but don’t let resentment about this live rent-free in your head.

Onward! Let’s all get vaxxed and start putting this nightmare behind us.