Today, the L.A. Times published my op-ed, in which I criticize California’s gubernatorial veto on parole which, as I explain in Yesterday’s Monsters, serves no purpose except contaminating the parole process with politics and optics. Here it is:

***

On Tuesday, California’s 2nd District Court of Appeal reversed Gov. Gavin Newsom’s veto of Leslie Van Houten’s parole, reinstating the state board’s parole grant decision. Their ruling exposes deep flaws in California’s system of allowing gubernatorial vetoes in the first place.

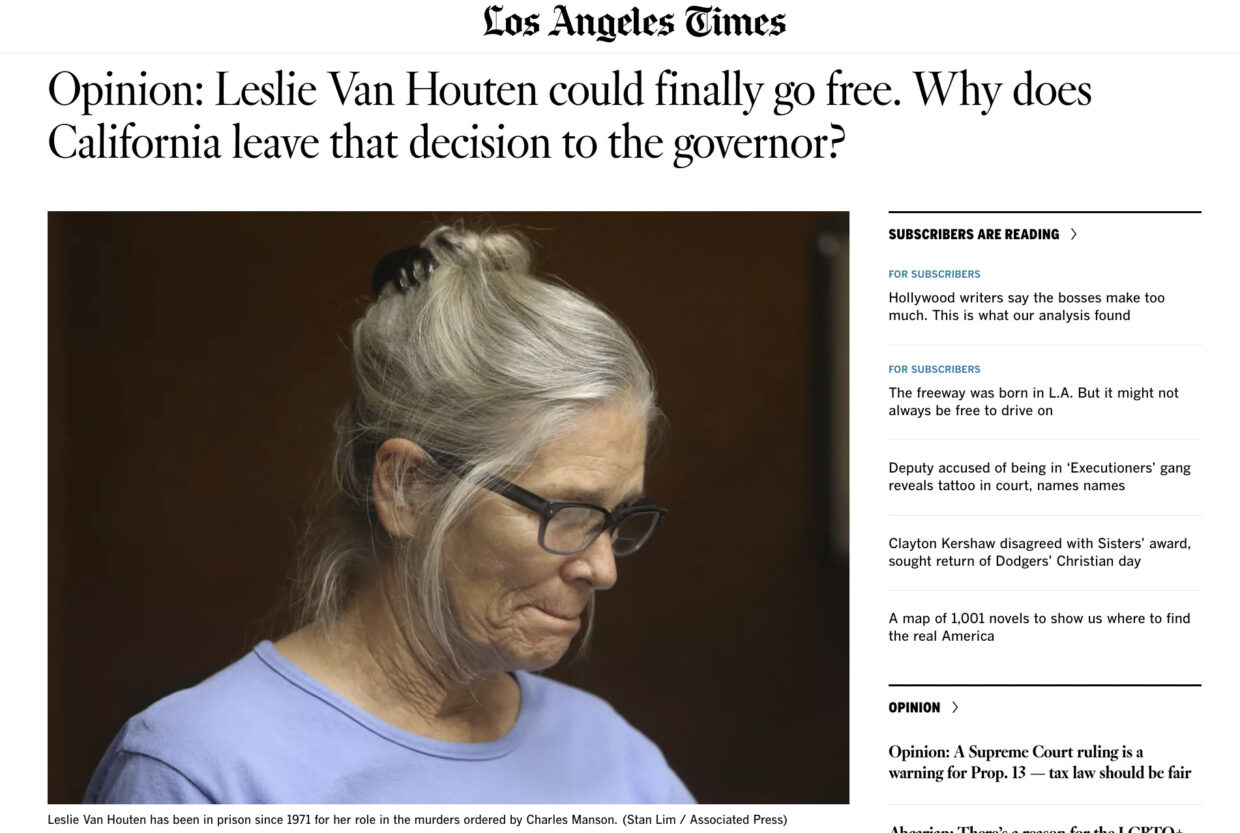

Van Houten, a member of the infamous Manson “family,” participated in the murders of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca in 1969. She was 19 at the time. These were horrific crimes whose aftermath shattered a sense of innocence and safety for many. But it is also true that Van Houten and other teenage girls caught in Manson’s web were indoctrinated into, exploited and abused by a dangerous cult not properly understood until many years after the murders.

In prison since 1971, with her original death sentence commuted to life with parole in 1972, Van Houten has transformed herself, earning two academic degrees, participating in rehabilitative programs and expressing remorse for her crimes. After decades of prosecutors and families of the victims of Manson’s crimes opposing Van Houten’s release, the factual evidence finally outdid the political pressure: Since 2016, the Board of Parole Hearings has recommended her release five times. Gov. Jerry Brown and then Gov. Newsom reversed each decision.

The appeals court reviewed the veto through a system deferential to the governor; all they needed to uphold his decision was “some evidence” that Van Houten, now 73, presents a risk to public safety. The court concluded that his veto was “not supported by a modicum of evidence in the record.”

Since a 2008 decision from the California Supreme Court, parole boards can’t deny release based solely on the severity of a crime. Instead, they must show that the parole candidate poses a public safety risk. Boards and governors alike have circumvented this standard by using hard-to-falsify language — for example, vaguely claiming that they don’t think the inmate possesses “insight” about their crime.

In denying Van Houten’s 2020 parole bid, as the appeals court reported, Gov. Newsom argued that her “explanation of what allowed her to be vulnerable to Mr. Manson’s influence remains unsatisfying.” He was also “unconvinced” that her childhood trauma, including her parents’ divorce and a forced abortion, “adequately explain her eagerness to submit to a dangerous cult leader or her desire to please Mr. Manson, including engaging in the brutal actions of the life crime.”

The court essentially called the governor’s bluff. They found that Van Houten’s extensive record showed “no additional factors Van Houten has failed to articulate, or what further evidence she could have provided to establish her suitability for parole. The Governor’s concern that there is more than meets the eye is, on this record, speculation, but [per state law] the Governor’s ‘decisions must be supported by some evidence, not merely by a hunch or intuition.’”

Yet allowing the governor to veto parole recommendations at all risks reducing such weighty decisions to one person’s hunch or political agenda. California is one of only two states that allow gubernatorial veto of parole. The Legislature introduced it in 1988, politicizing the parole process and adding public pressure — as well as optics — to what should be a professional assessment of risk. The veto works in one direction: The governor can only veto parole recommendations, not denials.

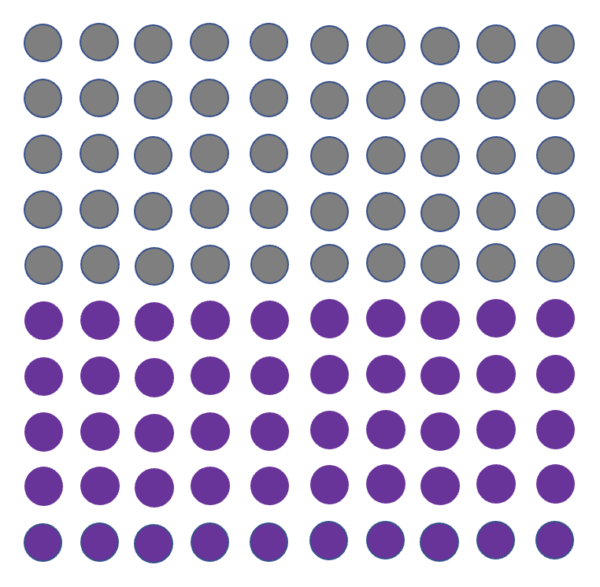

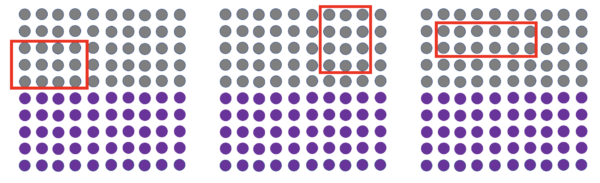

Any fear that the state is releasing dangerous people in droves is unfounded. Parole boards are reluctant to grant parole. According to data from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, the Board of Parole Hearings recommended it in only 20% of cases in 2019. As I explain in my book “Yesterday’s Monsters,” receiving parole at one’s first hearing is extremely rare. I found that the median time spent behind bars on a life sentence with parole in California has risen from 12 years in 1980 to 28 years in 2012 for those who have been released, and a quarter of the prison population is serving life sentences — 26,000 with parole and 5,000 without.

The role of politics was particularly clear during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aging and infirm lifer population faced serious risks of contagion and death behind bars. They also pose little to no public safety risk, as shown by robust criminological evidence. Still, Newsom agreed to release merely 8,000 people — a deficit eclipsed by incoming admissions from jails, and the vast majority with just weeks or months left of their sentences. Van Houten was up for parole in 2020 when her prison, the California Institution for Women, was experiencing a COVID-19 outbreak of more than 100 cases.

The court’s decision now puts the ball back in the governor’s court. He has a 10-day window, starting in a month, wherein he can instruct Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta to appeal this case to the California Supreme Court. Common sense should prevail and guide our leadership in Sacramento to allow this rehabilitated septuagenarian to live her life quietly on the outside.

But no matter the outcome, her journey raises serious questions about the gubernatorial veto. Do we truly need an extra layer of political considerations to assess danger to the public — or should we trust the professionals appointed by the governor, mostly from law enforcement backgrounds, to do their job?

Hadar Aviram is a professor at UC Law San Francisco. She is the author of “Yesterday’s Monsters: The Manson Family Cases and the Illusion of Parole” and co-author with Chad Goerzen of the forthcoming “FESTER: Carceral Permeability and California’s COVID-19 Correctional Disaster.”