On August 17, the Office of the Inspector General issued a report severely criticizing CDCR for its lax gatekeeping and symptom-checking practices. Today sees the publication of a new report, which addresses CDCR’s astonishingly lax PPE protocols.

Here’s a longish excerpt from the executive summary. I wanted to abbreviate, but decided it was best to let it speak for itself:

Beginning in March 2020, in an attempt to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 among its staff and incarcerated population, the department issued multiple statewide memoranda establishing its expectations and requirements regarding PPE, face coverings, and physical distancing. In April, to ensure its staff and incarcerated population had access to face coverings, the department purchased and distributed cloth face coverings manufactured by the California Prison Industry Authority and required that staff and incarcerated persons wear them in the prisons at almost all times. Although the department has since revised some of its directives, requirements governing the use of PPE, face coverings, and physical distancing remain in force as of October 2020

Despite nationwide shortages early in the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that the department was generally able to maintain supplies of PPE for its staff. Early in the pandemic, the department activated an operations center, which the department tasked with coordinating its efforts to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The operations center played a key role in evaluating and redirecting prisons’ PPE inventory as necessary. Our observations and interviews with staff at five sampled prisons suggest the department’s efforts in obtaining and distributing adequate supplies of PPE to its prisons were mostly successful. During our visits to those five prisons, we reviewed the prisons’ PPE inventories and spoke to various staff throughout the prisons, including those in the prisons’ health care clinics. During our visits, we generally observed staff in health care areas wearing appropriate PPE, and staff members we interviewed consistently stated that they had access to appropriate PPE, with just a few exceptions during the pandemic.

In addition, since April 2, the department has purchased more than 752,000 cloth face coverings produced by the California Prison Industry Authority, and by April 9 had delivered more than half of those face coverings to prisons for use by staff and incarcerated persons. The department generally appeared to be successful in distributing the face coverings to staff and incarcerated persons. During multiple routine monitoring visits, our staff rarely observed departmental staff or incarcerated persons who did not clearly possess face coverings.

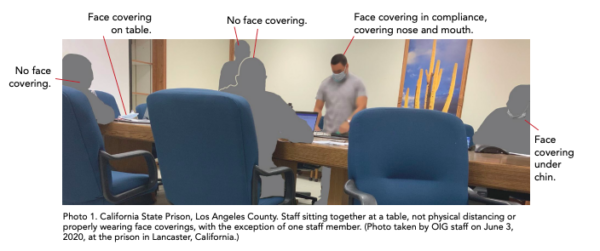

However, although the department distributed face coverings to its staff and incarcerated population, and the department issued memoranda communicating face covering and physical distancing requirements, we found that staff and incarcerated persons frequently failed to follow those requirements. As part of our customary monitoring activities that occurred between May 19, 2020, and July 29, 2020, our staff frequently reported observing departmental staff failing to comply with face covering guidelines during our staff’s multiple visits to 23 of the department’s 35 prisons. For example, during a visit to one prison, the Inspector General and Chief Deputy Inspector General observed multiple prison executives improperly wearing face coverings during a meeting that also included the prison’s warden, who did not attempt to correct the noncompliance.

Our observations were also supported by the departmental staff we surveyed at several prisons. To obtain prison employees’ perspectives, we surveyed all staff at seven prisons—more than 12,000 staff members. Of the departmental staff who responded to our survey, 31 percent reported they had observed staff or incarcerated persons failing to properly wear face coverings. Regarding physical distancing, 38 percent of the staff who responded to the survey stated they had observed staff or incarcerated persons not complying with physical distancing requirements.

The frequent noncompliance by staff and incarcerated persons was likely caused at least in part by the department’s supervisors’ and managers’ lax enforcement of the requirements. Despite the department’s then-Secretary’s statements during a legislative hearing on July 1, 2020, asserting that the department was enforcing its face covering requirements, and despite a memorandum the department issued on the same day, stating that it was vital for staff to adhere to face covering directives, we found that the department’s enforcement efforts have been very limited. In fact, based on records provided to us by five sampled prisons, prison supervisors and managers had taken just 29 actions—over a period spanning seven months—for noncompliance with the department’s face covering or physical distancing requirements.

One of the five prisons, California Institution for Men, provided no documentation of any disciplinary actions, and another of the five prisons, San Quentin State Prison, provided documentation of just one action. We found that almost all the actions that supervisors and managers took were instances of verbal counseling or written counseling, the lowest levels of the progressive discipline process. We also found that supervisors’ and managers’ failure to enforce COVID-19 requirements was not limited to the five prisons. Our staff reviewed every formal request for investigation and punitive action for the entire department since February 1, 2020, and we found that hiring authorities statewide only requested formal investigations or punitive actions for misconduct related to face covering or physical distancing requirements for seven of the department’s more than 63,000 staff members. We find that number surprisingly low, given the prevalence of noncompliance observed by our staff and by the departmental staff we surveyed.

In addition to inadequately enforcing its face covering requirements, the department perplexingly loosened those requirements at the same time it reported increasing numbers of cases of COVID-19 among both its staff and incarcerated population. Despite the increasing cases of COVID-19 in its prisons, the department sent memoranda on June 11 and June 24 relaxing face covering requirements for staff and incarcerated persons, respectively. The updated requirements allowed staff and incarcerated persons to remove their face coverings when they were outside and were at least six feet away from other individuals. Considering the volatile nature of a prison environment, the potential increased difficulty in enforcing the updated requirements, and the possibility that the virus could be spread even when people maintained a distance of six feet from others, the department’s relaxed requirements appeared to unnecessarily increase the risk of COVID-19’s spread among the staff and incarcerated population.

As of October 7, 2020, the department has reported the deaths of 69 incarcerated persons and 10 staff members due to COVID-19. Considering the risk that individuals without symptoms can spread COVID-19, and considering increasing evidence from the scientific community that face coverings are effective in slowing the spread of COVID-19, it is essential that the department’s staff and incarcerated population consistently wear face coverings whenever there is a chance they may come into close contact with other individuals. However, unless departmental management clearly communicates consistent face covering guidelines that are enforceable, and effectively ensures that its managers and supervisors consistently take disciplinary action when they observe noncompliance, the department will continue to undermine its ability to enforce basic safety protocols such as wearing face coverings and practicing physical distancing, thereby increasing the risk of additional, preventable infections of COVID-19 among its staff and incarcerated population.

After last week’s demonstrations of bad faith, I thought nothing could astonish me further. But what’s amazing about all this is that, throughout our litigation efforts in Marin County and in Von Staich, CDCR argued with a straight face that population reduction was unnecessary because they did such a good job distributing PPE and keeping protocols–and were then praised in the decision for doing so! Justice Kline wrote:

Respondents’ contention that the measures they have taken constitute a reasonable response to the risk posed by COVID-19 misconstrues the petition. Petitioner and the scientists he relies upon do not say the measures respondents took to combat the outbreak of COVID-19 at San Quentin are unreasonable in and of themselves, but only because they are unaccompanied by a dramatic reduction of the prison population, which is a sine qua non of any reasonable remedial effort. The target of the petition is not what respondents have done but what they refuse to do. None of the commendable steps respondents have taken to contain the spread of COVID-19 will be effectual, petitioner and his experts maintain, unless considerable room is made for inmates to physically distance themselves from one another effectively because, in the absence of a vaccine, physical distancing is now by far the most effective way of limiting transmission of COVID-19.

Except, as we now find out, the steps they boasted about taking, which the Court was misled into thinking were actually taken, were far from commendable! And in fact, could be “unreasonable in and of themselves.” You could bring a brand new deliberate indifferent lawsuit just on the basis of the OIG findings, without even getting into their resistance to reduce the population.

Just as one example of the rampant bad faith, here’s an image I screencaptured from the OIG report. It depicts a staff meeting at CSP-LAC which took place on June 3, a few days after catastrophe struck at San Quentin–and a whole month after CSP-LAC itself saw a serious outbreak.

Unsurprisingly, after the infection was already thought to have abated at CSP-LAC, there was a second outbreak.

It is especially unconscionable for me to read about the reluctance of prison administration to enforce mask wearing via punitive means–not because I think punitive means actually help (I’ve written plenty about why they are counterproductive) but because they have such a voracious appetite for handing out complaints, 115s, and 128s, at every occasion. When I worked on Yesterday’s Monsters, and when I read Kitty Calavita and Valerie Jenness’ book Appealing to Justice, I was dumbfounded by some of the silly minutiae that people got write-ups for (and then had to explain away, decades later, at their parole hearings.) It is astounding that a system that has an appetite for writing people up for having a quarter (yes, $0.25) in their pockets on a plastic spoon (miswritten as a knife) is so shy about penalizing its own staff (and the prison population itself) for not wearing masks.

All this is making me realize how right Peter Chin-Hong was when he said, at our June 9 press conference, that “prisons are incompatible with public health.” He’s now in good company: the American Public Health Association has issued a declaration that indicts the entire system for its contribution to social ills. As regular readers know, I’m not a great fan of sweeping slogans, but strip the declaration of all the tiresome jargon and you get to the bottom of the issue: it is outrageous to subject people to a system that makes all of us worse off, even at the lowest rungs of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

***

I also have a loosely-related coda: Twitter is awash with festivities over Governor Newsom’s amicus brief in McDaniel, in which he argues that ““California’s capital punishment scheme is now, and always has been, infected by racism.” If that is so, I call on Governor Newsom to account for the fact that more than twice as many people have died of COVID-19 at San Quentin during his moratorium than were executed in the entire state of California since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1978. The number of death row COVID casualties equaled the number of pre-moratorium executions as early as June 29. If the death penalty is such a disgrace to the Governor–and I agree, it is indeed–why are people still dying on death row, in larger numbers, and why are we still paying for it? The key to this problem is obvious, it’s in the Governor’s hands, and it has nothing to do with amicus briefs. All of these sentences, as well as LWOP sentences, could be commuted today.

1 Comment

[…] management of the COVID-19 pandemic at its institutions. The tone of the hearing was largely set by the recent Inspector General report, which found serious fault with CDCR’s enforcement of proper PPE attire by staff and […]