I was quietly reading Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass and thinking about yesterday’s post on the interconnected dance of life, when Facebook, with its indelible memory, reminded me: It is six years to the day that my colleague Dan Markel, a criminal law professor at Florida State University, was murdered, shot to death in his garage.

The sensation of shock, like unsavory gray smoke filling my lungs, making me nauseous with incomprehension, has stayed with me, and seems to have been universal. Dan was so alive–isn’t that what is always said of the dead?–a true, energetic community builder, the architect of Prawfs Blawg, the inaugurator of CrimFest, both of which have outlived him. A loving father to his two young boys, of whom he always spoke with such affection. The nauseating smoke whispered, how? why? who? Theories spread among Dan’s friends and colleagues; blogs were ablaze, picking up the shreds of Dan’s life, looking for some conflict, strife, danger, something that would explain the unexplainable. Underneath it all, unspoken save, perhaps, in the offices of my friends’ therapists, was the uncomfortable but true realization, this doesn’t just happen to someone I know. People living comfortable lives of safety and social advantage, lives that do not grow in the shadow of street violence or require it, were deeply unsettled. If we could only find out why, we felt, perhaps, this senseless thing will make sense; something in Dan’s life, in his relationships and entanglements, would make sense of this out-of-place death.

The mystery of Dan’s murder lingered on, picking up steam occasionally on blogs, for two years. Whenever I met other friends and colleagues of Dan’s, we shook our heads. “We just want to know what happened,” we said. The aching gap Dan left in the professional and social fabric of our trade was lovingly mended by friends who took the mantle of organizing. Then, two years later, we found out. It was sordid, disturbing, the stuff of low-grade cold-crime television shows in which a deep-voiced anchor dramatizes the events. They were Luis Rivera, 33, and Sigfredo García, 34, murderers for hire, and the only plausible connection between them and Dan was the mother of García’s children, Katherine Magbanua, who was dating a rich Florida dentist, Charlie Adelson.

Adelson was Dan’s brother in law. Dan and his ex-wife, Wendi Adelson, had divorced in 2013, and were amidst an ugly custody battle; Dan had won an order prohibiting Wendi from moving to Miami with the children, and filed a motion that would have prohibited Donna, Wendi’s mother, from being alone and unsupervised with the children due to alleged disparaging remarks about Dan. The investigators alleged Magbanua made the connection between the Adelson family and Garcia , that she received a large amount of money from the Adelsons following Dan’s murder, and that Magbanua was the first call Garcia dialed after Markel was murdered.

All this added up to arrest warrants against García, Magbanua, and Rivera, but not against the Adelsons. Despite repeated efforts to trip them, they have eluded law enforcement efforts at gathering more evidence against them. Rivera turned state witness, García was convicted, and Magbanua, who remained steadfastly silent even in the face of a threat with Florida’s death penalty, won a mistrial (ten jurors voted to convict, two to acquit.) Magbanua is to be retried for the murder. Much as I find it loathsome and distasteful to lionize and sanctify the three apprehended parties to a murder-for-hire because they are “poor people of color,” I can understand and empathize with the sentiments of injustice: the rich and powerful have managed to escape all consequences of their likely actions. Given what we know, what plausible explanation could there be for all this except the Adelsons’ desire to get Dan out of the way? Not one member of the Adelson clan evokes even a shred of sympathy: In a particularly cruel move, Wendi Adelson immediately proceeded to remove Dan’s last name from those of the children and denied them contact with their paternal grandparents. And yet, the police claims not to have cobbled enough probable cause for an arrest.

Thing is, what I think happened and what the law, which requires stringent beyond-reasonable-doubt proof, asserts happened, are two different things. The law does not operate in a vacuum, and people of means have many ways to insulate themselves from incriminating behavior and paper trails. I know many of my friends and colleagues who grieve for Dan hope for justice in the form of criminal consequences for the Adelsons. Much as I fail to comprehend the moral makeup of the Adelsons, I’ve always been pretty clear on the fact that I would not feel even a little bit better about this tragedy if I heard that the police arrested Donna, Charlie, or Wendi. Moreover, I didn’t feel relieved or vindicated when the police waved the threat of capital punishment over Katherine Magbanua’s head. Not only did it not work, in Magbanua’s case, and not only does this use of the death penalty as a bargaining tool create ugly disparities between sentences in abolitionist and retentive states, but I found the whole entanglement with the worst aspects of Florida’s criminal justice system tasteless given Dan’s own scholarly stance against the death penalty. My conversations with many of Dan’s friends and colleagues revealed that they, too, felt like knowing what had happened and making their mind about the culprits was sufficient. What horrors, albeit deserved, could the criminal justice system possibly visit upon the Adelsons that would make us feel better about the grievous loss of our friend?

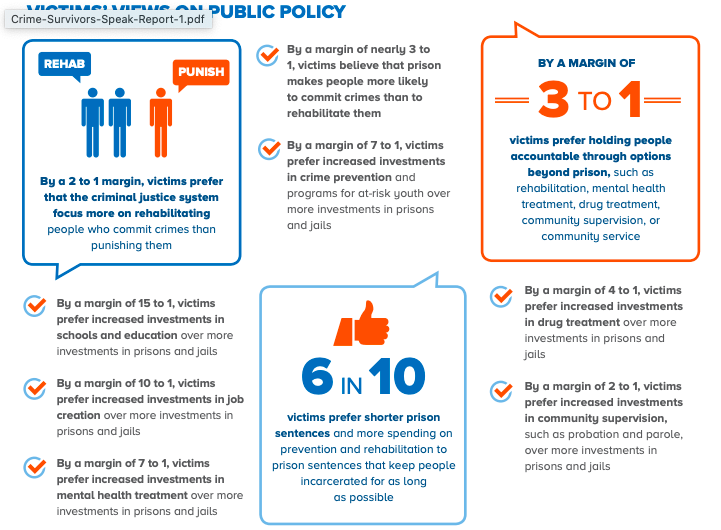

I’m not particularly surprised that so many people’s grief over Dan’s death didn’t manifest as a desire to see his killers–all of them, including the ones too dainty to pull the trigger–harshly punished. I see the same from families and friends of homicide victims all the time. The first-ever national survey of crime survivors show that victims are far less punitive than Twitter would have you believe.

Not everyone is nonpunitive, of course. The Tate family, whom I discuss at length in my book Yesterday’s Monsters, were instrumental in shaping public perception of what victims want, as was Mark Klaas. I don’t think any of these people has been manipulative or insincere or has not suffered unimaginable pain; I do think, however, that their voices are mistakenly assumed to represent what most victims want, which is not the real picture. Nor is this an illness particular to the conservative right; the fault lies just as much with the folks who wrote fashionable pieces about how Jean Brandt’s act of faith and forgiveness toward Amber Guyger was “problematic” in that it “allowed whites to benefit from black forgiveness”, because some people on the left are apparently so enlightened that they can educate people on how to properly grieve their relatives. I saw the same dynamic in some of the astonishing reactions on Christian Cooper’s sane and measured response to the police investigation of Amy Cooper’s false complaint about him to the police, those accusing him of “performing a disservice” to African Americans nationwide, because apparently (1) everything has to be a performance and (2) the only true path to social justice is through arrests, charges, and convictions.

Why is all this making me so sad today? Because amidst these frightening times, that should by right make all of us deeply grateful for life and concerned to preserve its fragility, incomprehensibly, the federal appetite for executions reached a boiling point, and sometime last week, while we were all asleep, the Supreme Court kosherized three executions. Each, in its way, highlighted the deeply misguided aspects of the death penalty. Daniel Lewis Lee was put to death against the express, vocal, and repeated wishes of his victims’ families against his execution. Wesley Purkey’s execution of a “severely brain-damaged and mentally ill man who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease,” whose lawyer, Rebecca woodman, said does not understand “why the government plans to execute him” was a grim reminder of the idiocy of incessant, expensive litigation to ensure that people are healthy enough to be killed by the state; And Dustin Honken’s attorney, Shawn Nolan, underscored the fallacy that people are unchanging and irredeemable: “”There was no reason for the government to kill him, in haste or at all. In any case, they failed. The Dustin Honken they wanted to kill is long gone. The man they killed today was a human being, who could have spent the rest of his days helping others and further redeeming himself.” In keeping with the usual pattern of death penalty litigation, which Justice Harry Blackmun called “tinkering with the machinery of death“, the dissents were all about method and process, rather than about the heart of the matter.

That this–a reaffirmation of our government’s commitment to a punishment that is, itself, dying a slow death (like many of death row inmates themselves)–is our takeaway from this pandemic, is mind boggling, but I see the same mentality among those wondering why we worry about people on California’s own death row catching COVID-19. Being on death row is hardly a natural consequence of one’s actions, as so many of my colleagues have explained over the years, and so the shrugging of shoulders, accompanied by a more or less crude version of “you do the crime, you do the time” or “we have to make priorities” astounds and perplexes me. As we inch toward November, the urgency of a vote that affirms everyone’s value in the dance of life becomes clearer and clearer. And then, we begin the hard work of reshaping the arc of progress, which has taken a very, very wrong turn.

No comment yet, add your voice below!